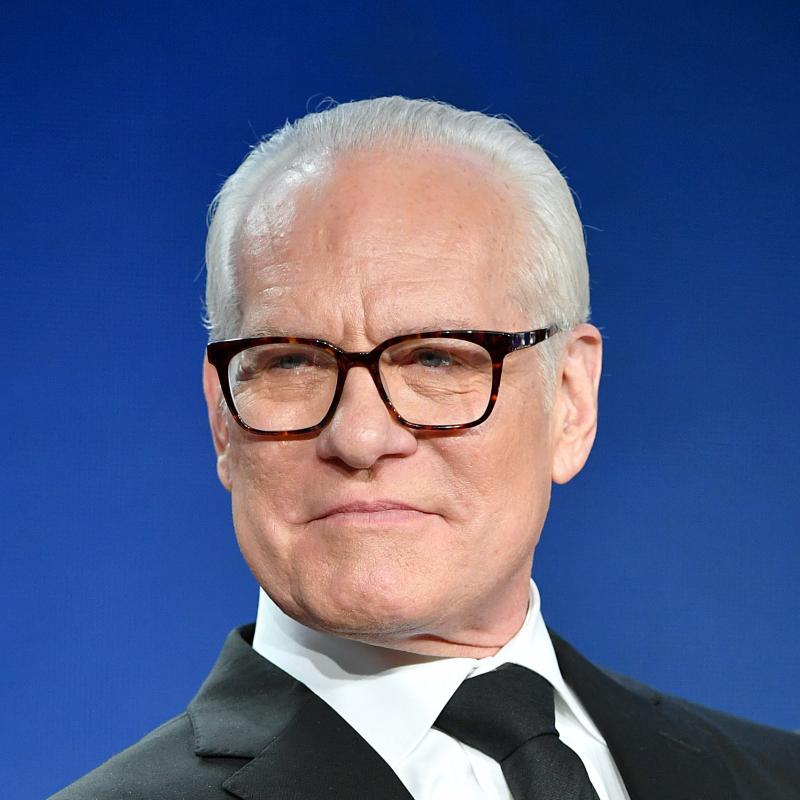

Don't Worry, Even Fashion Guru Tim Gunn Is Living In His Comfy Clothes

Fashion expert Tim Gunn used to bemoan what he called the "comfort trap" — clothes that prioritized comfort over style. Now, after weeks of self-isolation in his New York City apartment amid the COVID-19 pandemic, he's reconsidering his stance.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Tim Gunn, became famous for his role as a mentor on the fashion competition series "Project Runway." Now he hosts a new fashion competition series called "Making The Cut." The entire series, including the recent finale, is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video. Gunn created and co-hosts the show with Heidi Klum, who he also appeared with on "Project Runway" for over a decade. "Making The Cut" brought together designers from around the world, flew them to Paris and Tokyo and challenged them to design runway and street fashion that was eco-conscious and able to fit all body types and gradations of gender.

Unlike on Gunn's previous fashion competition shows, these designers were already experienced entrepreneurs. They had to demonstrate they'd be capable of creating a global brand. The winner received a prize of a million dollars. Throughout the series, Tim Gunn serves as a mentor to the designers. Earlier in his career, he was a teacher and chair of the fashion design department at Parsons School of Design at the New School.

Tim Gunn, welcome back to FRESH AIR. It is really just such a pleasure to talk with you again. How are you? You're living in Manhattan, which is the hotspot in the country.

TIM GUNN: Well, Terry, first of all, I'm so thrilled and honored to be back speaking with you. And thank you so much. I have to tell you, New York is - it's surreal. I mean, it feels quite apocalyptic. I will say this, though, there are fewer sirens at the moment. There are visibly more people out - not a lot of people, of course. And people were wearing masks, thankfully. But the city feels as though it's picking up again, just slightly.

GROSS: I know you like being alone. I know you like living alone. Are you going through too much alone now? And if so - how are you dealing with it?

GUNN: Well, you're quite right. In many ways, this self-isolation appeals to me. But when you feel as though someone has a bayonet in your back, which, in fact, metaphorically, they do, it takes a toll. I mean, I'm, thankfully, fine physically. But psychologically, it's troubling. And it's not just about not being able to interact with people or go to a restaurant, which I didn't frequently anyway? But, I mean, for me, the greatest soul stir that I have is in a state of suspension. And that's the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is just across Central Park from my apartment. And I used to haunt those galleries. I was there at least twice a week. And it's really left a void in my life.

GROSS: What other things do you - have you had to give up? And have you been finding replacement things, replacement routines that give you both a sense of structure and a sense of kind of comfort or equilibrium, equanimity?

GUNN: Well, I've been doing a kind of life inventory of what's important to me, what isn't, including things that I own. I've been doing a lot of writing. And I've been doing a lot of reading. And I've been engaged in a lot of introspection. And I think that that's good up to a point.

GROSS: Yes. (Laughter) I know.

GUNN: And then it can just become tiresome (laughter).

GROSS: It could be kind of damaging. I mean, there's a point where...

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. Self-criticism is good. And then it gets bad.

GUNN: Yeah. I totally agree. And I have to say, too, I'm such a lucky person. I have to remind myself of that because you can very easily fall into this trap of self-pitying. And I think, good heavens. I'm so lucky. I have a home. I have resources that will get me through the storm. I have people I care about and who care about me. And it's - I'm very, very, very lucky. And I need to slap myself when I start wallowing in this self-pity.

GROSS: I'm wondering what you think the meaning of clothes is now because most of us are at home. And if we're going out, like, we're wearing a mask. It's like, you're not going to look good. Do you know what I mean?

GUNN: Yes. Exactly.

GROSS: (Laughter) It's like the mask kind of ruins the look no matter what it is. Most people at home are wearing, like, sweatpants or pajamas or old jeans. And I'm wondering, like, what you're wearing now. And what is the meaning of clothes? Is the meaning of clothes changing as we're all, like, self-isolating?

GUNN: It's been a very interesting experience for me because I've gone through an evolution in these last five, 5 1/2 weeks - a fashion evolution or a clothing evolution of sorts. And it's helped me to understand a lot of issues that I've talked about in terms of the sorts of things that I observe in other people. And one is, I now understand the comfort trap. I used to bemoan it and say, you know, if you want to dress to feel as though you never got out of bed, don't get out of bed. Well, now I understand.

I mean, why should we be self-isolating in clothes that constrain us and constrict us and are not as comfortable as something that's a little looser and more forgiving? However, (laughter) I will say this. Having been introduced to video conferencing, which I - was unknown to me until this self-isolation - having been introduced to video conferencing, I've dressed up for it after, say, days of wearing, quite frankly, my pajamas and a robe. And when I got into my normal clothes - a proper shirt, a proper pair of pants, a jacket - I felt as though I was wearing a wet suit.

GROSS: (Laughter).

GUNN: I felt so tethered, so tied down. And I thought, oh, this is bad. I need to start wearing regular, normal Tim Gunn clothes more often, because that feeling, I understand it. I've worked with women, in particular. And sort of - I won't call it a makeover. I'll call it a make-better. And she'll call out from the dressing room, this jacket is too tight. Just come out of the dressing room wearing it. We'll look at it together. And I'll say to her, it's not too tight. It's exactly the size it should be for you. You're used to wearing clothes that are, frankly, too big for you. So I'm understanding people and their fashion foibles a lot better now. I have more empathy. I get it.

GROSS: So when you're wearing pajamas and comfortable robes at home, are they beautiful? Or are they just, like, no one's going to see them, so they're just whatever?

GUNN: Well, I wear a T-shirt on top, just a white - classic white tee, and pajama bottoms and a cotton robe that's navy. And it's presentable. I mean, I won't leave my apartment. I won't even go to the trash chute at the end of the hall wearing that. So it's a kind of pact that I make with myself. If I'm wearing this, I stay in. I do not open the door. I'm not going down to the first floor to get the mail.

So I - yeah. I make a pact with myself that I am not to put myself in a position where I may run into a neighbor. So that's the condition. And I'll add, every third day or fourth day, I go out to the grocery store, which is just at the corner, thankfully. And of course, I get dressed for that, but not - I mean, I have worn a sport coat and a tie a couple of times for video conferencing reasons. But usually, I'm dressed the way that I am now. I'm in a turtleneck and a pair of dark wash jeans.

GROSS: I keep getting emails because I do some shopping online from all these places that are having sales. And I keep thinking, who cares right now about buying clothes? Who knows what season you'd even be shopping for? And it just makes me wonder, like, what's going to happen to, like, clothing retail?

GUNN: Oh, I know. I considered the same thing, and it's quite a conundrum. I will say this, though. We know that online shopping is here to stay. I worry about bricks and mortar. But when it comes to purchasing things, I'm exactly like you, Terry. I haven't bought a thing since the - since being shut in on because I asked myself, well, what and why? When we get out of this - which we will eventually - we'll have a much better sense of what we want and what we need. Also, part of this inventory (laughter) that I've been doing has been closet inventory, taking stock of what I wear all the time, what I don't, what I haven't worn for a year or more. And it's resulted in a purge that's been - has made me feel physically lighter, actually. And I know where the holes are in my wardrobe, and I know where I have too much. And it's something that I think everyone should engage in. And this - these stay-at-home orders are a great opportunity to do it.

GROSS: Let me reintroduce you here. If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn, who became famous as a fashion design mentor on the fashion competition series "Project Runway." His new series "Making The Cut" is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video. It's also a fashion competition series, but this is a global one with designers who are already experienced designers and entrepreneurs. We'll be right back after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF AWREEOH'S "CAN'T BRING ME DOWN")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with Tim Gunn. His latest fashion competition series is called "Making The Cut." The entire series is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

What's it like for you to have a new series about fashion during the pandemic when, if people are going out, they're going out in a very limited way and mostly, as we've been talking about, they're staying home wearing pajamas or shlumpy (ph) clothes?

GUNN: Well, to be honest with you, Terry, my co-host Heidi Klum and I talked about this when we heard when the show was going to start airing, and we were really concerned about it. And we thought this seems to be in very egregious, bad taste to do this now. And Amazon listened to us and understood and said, you know, this is really a feel-good show. It's uplifting. It's inspiring. And people will want this at this time. People feel shaken. They feel derailed, off-center, and this show is very grounding, and it's a good time to release it. And I thought, they're right; it really is. And the response has been quite phenomenal.

GROSS: Yeah, I mean, it's a period when you can't wear, like, special clothes because there's no point, but it's fun to watch (laughter).

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: It's like, you can watch the thing that you can't actually do yourself. So I think it's, in that sense, like, a really good time for it to come out. Do you feel like...

GUNN: Yeah. I mean...

GROSS: Yeah.

GUNN: ...People can get a vicarious thrill out of it.

GROSS: Do you feel like you learned anything about fashion inclusivity by hosting, you know, by being the mentor on the show where that was part of what the designers were tasked with? They had to think that way. They were probably already thinking that way. But...

GUNN: Oh, most definitely. But I have to say, when I became chair of the fashion program at Parsons, inclusivity was a mantra of mine and a mandate, including the dress forms. I thought, why is everything a size 6. This isn't realistic. And why are our fit models a size 4 or 2 or 0? And I began bringing in models of all - fit models of all sizes, expanding the sizes of the dress forms and even - this is not entirely a non sequitur, but it may sound like one - but even bringing in people - PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals because the department had a history of working with fur. And I thought this - I have a responsibility to these students to give them as many sides of these equations as possible. It greatly enhanced the thinking of these young designers, and it introduced a very substantive and important conversation about ethics and morals and, also, about accepting responsibility for the decisions that you make.

GROSS: Your role as a mentor, like, there are times - like, you are very honest in your criticisms. You're honest with your praise. And you're honest with your criticism. And because you're trying to be precise in your criticism - not cruel, but just precise - sometimes one of the designers is on the verge of tears. And of course, this is on camera. How do you feel about that? You've been a teacher for so many years. Of course, you were a teacher at Parsons long before you became a mentor on TV.

GUNN: Well, as a teacher, I went through tremendous growing pains and learned through trial and error what works and what doesn't. And I learned early on that you can't soft-pedal and sugarcoat things because it doesn't help the student. I also learned early on that you can't be too blunt an instrument in delivering critical analysis because if you are, you're discredited. The student just dismisses what you say as being mean-spirited and unkind and believes that you don't understand their work. So I developed what I call a very Socratic approach. I pummel people with questions because I need to know where they're coming from. I need to know a context before I dive in with my own analysis.

And for me, the ideal is - this is what I really strive for. The ideal is to get the individual with whom I'm speaking to see what I see. And on "Project Runway" for 16 seasons and on "Making The Cut" for this one season, there are occasions when I disrupt production in a manner of speaking because of camera placement, and I ask the designer to come stand next to me so they can see their own work from my point of view. And I say I disrupt production because there's a camera on me, there's a camera on the designer, and when we switch things up, the people in the control room get a little frantic.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: But I want that designer to see the silhouette, the proportions, perhaps even the construction - though on "Making The Cut," it's not a sewing show, which is a huge relief. The designers are making clothes, but it's not about, is the hem crooked? So for them to stand by me and say, oh, I see, that aha moment, for me, is the sweetest, most wonderful thing in the world. It's like, OK, I can leave you now because you get it; you see it. What you do about it is completely up to you, but at least you see what I see.

GROSS: You know, there's one designer who mostly does fashion in black. And at one...

GUNN: Oh, Esther.

GROSS: Yeah. And at one point, you say to her, it really needs a little bit of color. And she says, that's not me; I have to be true to myself, and I see it as black. And so it struck me, like, that must have been a kind of difficult balancing act for you because you want somebody who has a vision, who knows what their vision is and believes in that vision but, at the same time, you thought, you know, could really benefit with, like, a little bit of color (laughter). So...

GUNN: Well, I...

GROSS: Yeah.

GUNN: I was reflecting upon the comments by the judges. And of course, with each individual assignment, once it's presented, someone's going home. And I was very concerned about Esther, a superbly talented designer and also a wonderful individual. I really adore her. And I said to her, look - color. You're used to black. It is a color, but it's one color. How about merlot? How about chocolate?

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: I mean, we're talking about slight nuances off of black, but it's still - but it's a color. It will show that you're synthesizing what the judges are saying to you and you're - and here's a product to show it. But no (laughter), chocolate was too much of a color for her or too much of a departure.

GROSS: Well, I won't give away how she does.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: OK. So you came to see teaching and mentoring as a calling. But when you started teaching, you had stage fright. You'd actually, like, throw up before classes.

GUNN: Oh, I was a wreck. And I had been - oh, I wouldn't - I won't call it student teaching. I was a teaching assistant the summer before the fall that I began teaching, and I loved it. I was perfectly relaxed and comfortable. I was fine. And then this teaching position was - well, was thrust upon me, in a manner of speaking, by my mentor - one of my favorite teachers of all time, Rona Slade. She said that a faculty member had dropped out from teaching three-dimensional design and would I like the position. Well, of course. I mean, A, yes I would, but - and also, I wasn't going to disappoint Rona.

So the very first day, I pull into the school's parking lot, and I promptly throw up all over the asphalt. And I'm shaking and shaken. And I get to the studio where I'm teaching and just the mere anticipation of the students coming into the room has me trembling. And - so I braced myself against one of the walls. My back is against it because if I step away from it, I'm just going to collapse to the floor. I mean, I needed that support. So this went on for a week - well, five days.

And on Thursday of that week, I rehearsed the meeting I needed to have with Rona, and on Friday, I had the meeting. And the rehearsal was brief, I mean, because it didn't require many words. And I just said to her, I can't go on like this. This is just completely debilitating. My health is suffering. I am not sleeping. I'm an emotional wreck. I can't go on like this (laughter). So Rona, who's Welsh, said in this very clipped voice of hers that she trusted that this experience would either kill me or cure me. And she said, and I'm counting on the latter. Good day.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Oh, that's so great.

GUNN: And who knew? I mean, 29 years later, I was still teaching. I mean, I grew to just completely love it.

GROSS: My guest is Tim Gunn. His new fashion competition series "Making The Cut" is now streaming - all the episodes, including the finale, on Amazon Prime Video. We'll talk more after we take a short break. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with Tim Gunn, who became famous for his role as a mentor to fashion designers on the fashion competition series "Project Runway." His new series, "Making The Cut," is a global competition fashion show. And all the episodes, including the finale, is now on Amazon Prime Video. So you became a teacher. But as we talked about in our previous interview, you really hated school.

GUNN: Oh, yes.

GROSS: And you went to several boarding schools, right?

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: Then you ran away from school. I was wondering, like, what was your technique when you ran away? Like, where did you go? Did you slip out a window in the middle of the night...

GUNN: (Laughter).

GROSS: ...Like I see in movies? Like, what would you do?

GUNN: Well, I used to run away and never leave the house. I was extremely good at hiding and not making a single movement. But...

GROSS: When you say never leave the house, you mean your home or the house that you were living in the boarding school?

GUNN: No. Well, the running away began when I was still living at home.

GROSS: I see. OK.

GUNN: And I became very good at it. And then my parents brought in more resources, namely our family dog, who was always able to sniff me out.

GROSS: (Laughter) God.

GUNN: So then I would run away from home and go to Rock Creek Park, which was right behind us. This is in Washington, D.C. But then the dog would - my mother would come out with the dog on a leash. And the dog would find me. Brandy (ph) was her name. So then I started running away with the dog, thinking, well...

GROSS: (Laughter).

GUNN: ...I'll have her with me. But then I realized, she'd get hungry. She'd be thirsty. So then I used to run away with water and snacks for her. But at boarding school, I mean, there was only one really dramatic running away. And it was after - I know we talked about this. It was after a suicide attempt. And then I woke up. And I was still there. And I ran away to - this school was on - in Connecticut on Long Island Sound.

And I ran away to hide in woods next to a beach. And there were police walking up and down the beach. And I was paranoid enough to think that they were looking for me - maybe they were, maybe they weren't. But then it got dark. So I went back to the school, knocked on the headmaster's door - it was probably about 8 or 9 at night - and just burst into tears and fell to my knees. And he was incredibly kind and wonderful.

GROSS: What did you say to him?

GUNN: Well, I mean, he had a huge look of relief. The school knew I was missing. And what I remember more is what he said to me, just being very consoling and very - he was a good listener. And he said that my parents had been called and that they were on their way. Yeah. I had a - I mean, in some ways, I hate reflecting upon it because it was so painful. At the same time, I was so lucky to have a family that really did care. I mean, I gave them nothing but heartaches and trouble. But they were - they never abandoned me. They never said, OK, you're on your own.

GROSS: Yeah. The last time we talked, you mentioned a doctor. After you took about a hundred pills and tried to kill yourself and then found that you actually woke up and you were in a psychiatric hospital for adolescents for a couple of years, you mentioned that there was a doctor who, no matter how much you tried to push him away, he stuck by you...

GUNN: Yes, Philip Goldblatt.

GROSS: ...And that helped you so much.

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. I'm wondering if that shaped your approach to being a mentor at all.

GUNN: You know, Terry, I've never considered it. And as you say it, it had to have shaped me. You know, I mean, for anyone who didn't hear our earlier conversation several years ago - I was in this hospital and was very proud of the fact that I successfully outwitted psychiatrist after psychiatrist. There had only been two before Dr. Goldblatt. But I was successful just stonewalling them and not speaking in sessions. And eventually, they just stopped having sessions with me and allowed me to be in group therapy sessions.

And when Dr. Goldblatt came, it was after I'd been there for three months. And he was young, right out of his residency. And I thought, oh, this will be a piece of cake (laughter). And after a couple of weeks of this - I don't know whether I introduced it or he introduced it. But one of us said, is this the way it's going to be? Or for me, it would have been a declarative sentence. This is the way it's going to be. So he said - what he said to me was, well, I'm not going to meet with you three days a week. And I thought, oh, OK. It's working. He said, I'm going to meet with you five days a week...

GROSS: (Laughter).

GUNN: ...Thought, what? So he really broke me down but with kindness, with nurturing and with indefatigable patience. It was - he's a remarkable, remarkable man.

GROSS: How much do you think feeling marginalized, yourself, when you were in your teens had to do with being gay and not coming out to anybody, and maybe not even coming out to yourself for a while?

GUNN: Oh, and I didn't come out to myself. You're quite right. I mean, I knew what I wasn't. I knew I wasn't a heterosexual male. But I didn't know what I was. And I had a terrible fear of intimacy. And quite frankly, I won't call it a fear today at age 67. I just accepted it's a very matter of fact. I don't have a desire to be intimate with anyone. I have to say that there were people in the hospital that - where I was as a teen who were there because they were gay. They were there to be fixed. And I felt simultaneously horrified and sad and terrified.

I thought, well, that can't be me, too. I have enough issues. And I came to terms with this in my very early 20s. And it was extremely liberating. It was, at that time, probably the happiest I'd felt. And I may have told you, I only came out to one person, and that was Dr. Goldblatt. I took the train to New Haven from Washington. And I'd made an appointment to see him. And because, you know, I've been - I was - your question is a catalyst for me to really think about this. I believe I went to him for his validation. And I - sorry. Terry, you're able to get me to well up no matter what.

GROSS: (Laughter).

GUNN: But he gave it to me.

GROSS: What was the form of the validation?

GUNN: Just that he accepted it and basically said it's - and everything's all right, isn't it? Yeah. It is.

GROSS: Let me reintroduce you here. If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn, who became famous for his role as a mentor to fashion designers on the fashion competition series "Project Runway." His new series, "Making The Cut," is a global competition fashion series that's now streaming on Amazon Prime Video - all the episodes, including the finale. We'll be right back after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JEFF COFFIN AND THE MU'TET'S "LOW HANGING FRUIT")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn. His latest fashion competition series is called "Making The Cut." The entire series is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

You know, one of the things we talked to - one of the things you told me the last time was that your father worked with J. Edgar Hoover when Hoover was the head of the FBI. And he wrote Hoover's correspondence. He wrote his speeches. He wrote his autobiography, if I remember correctly. And then your mother started the CIA library.

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: You had parents who helped keep the secrets...

GUNN: (Laughter).

GROSS: ...And then helped store the secrets. And then you had this huge secret from them. And I just kind of put that together recently thinking about that and thinking about what I wanted to talk with you about, that they couldn't accept your secret. Like, even when your mother knew you were gay because she saw you on TV (laughter)...

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: ...You know? Like, she would not engage with you and talk about it. Like, it was just, like, off the table. And I thought, like, gee, how does that fit with the whole Hoover thing and the CIA thing? Like, a family that was all about, like, understanding secrets.

GUNN: That's a very interesting series of thoughts, frankly. Yeah. And my father in particular - by the time I was born, my mother had left her position. But my father, of course, was with Hoover for 26 years. And he was very private and secretive. Did I tell you about him - Dad bringing home the Warren Commission, the report about the...

GROSS: No (laughter).

GUNN: ...The Kennedy assassination?

GROSS: No, no.

GUNN: He brought home the Warren Commission before it went to Congress. And I don't know what possessed him. But he - I think he was just proud to have it. And he told my mother. Well, after dinner, I can hear the water running in the bathtub of my parents' bedroom. And Dad's watching television or something. Mother's gone. And it turns out Mother's in the bathtub with the Warren Commission. So Dad figures this out. He knocks on the door, it's locked. He asks her to open the door, she refuses. He gets an axe and takes the door down...

GROSS: No.

GUNN: ...To get the commission - the Warren Commission out of her hands.

GROSS: Because it was so secret.

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: And this is the report on the Kennedy assassination. Like...

GUNN: Exactly.

GROSS: Yeah. Wow.

GUNN: That was a...

GROSS: He had an axe (laughter)?

GUNN: Well, in the basement or in the garage. That was a - that's a potent memory (laughter). I'll never forget.

GROSS: What were you doing when that happened?

GUNN: Crying.

GROSS: (Laughter).

GUNN: You know, Dad, stop.

GROSS: OK. So this is an example of the extremes your father would go to to keep the secret.

GUNN: Keep a secret, exactly. Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. So when confronted with your secret, it's like they didn't want to know, huh?

GUNN: No. Well, I - you know, I think my father must have known also. He died before I even took over the fashion department. That would have killed him. But - well, I think I may have said to you before also, my father's closest friends were all FBI people. They were all bureau people. And they would be at our house every Sunday in the fall watching the football games. And I have to tell you, Terry, it was the gayest gathering I think I've ever seen anywhere.

GROSS: (Laughter).

GUNN: It just was. I just - I'm confident that Hoover's FBI was just a hotbed of closet cases.

GROSS: Really? What makes you say this? And it's a lot of speculation that Hoover was gay.

GUNN: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: I don't know. Is that confirmed?

GUNN: Well, I mean, we do know he was a cross-dresser.

GROSS: Right. OK. Well, that's very interesting (laughter). You know, we were talking about how your family kept secrets. Like, your father was - you know, wrote correspondence and the autobiography for J. Edgar Hoover when Hoover was head of the FBI. And your mother started the CIA's library. You are very open now. And that's part of what you've done as a mentor, because you've not only been a fashion mentor. But I think you've been a lot of mentor to - you've been a mentor, even if it's just long distance, with a lot of young gay people who are coming out. You did a great It Gets Better video a few years ago. And so you've been open about your life. How do you think having kept your own sexual orientation secret and having grown up in a family whose job was to keep secrets, how did that affect your decision to be open about your life?

GUNN: Well, quite frankly, Terry, it's a process that evolved. I mean, there was a point when I had so many secrets and so many barriers and blockades of my own making that each time one went away because I talked about it, revealed it, I would feel physically lighter. And it's just a huge relief. It's why I say don't lie about anything because when you lie, you have to remember what you said to whom, about what and what it was. When "Project Runway" started and I was being interviewed, occasionally, my mother said to me, I just read this interview - why aren't you lying about your age?

GROSS: (Laughter) Yeah.

GUNN: What? Why would I do that? And it turned out later, I found out, that she was lying about her own age. So she was lying about how old I happened to be. It's just so much more of a pleasure and a real joy to just - to not have any secrets.

GROSS: I need to take a short break here. So let me do that, and then we'll come right back. If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn, who became famous as a fashion design mentor on the fashion competition series "Project Runway." His new series "Making The Cut" is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video - all the episodes, including the finale. We'll be right back after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAMES HUNTER'S "I'LL WALK AWAY")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my interview with Tim Gunn. His latest fashion competition series is called "Making The Cut," and the entire series is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

People have been saying, like, we've never lived through anything, not since 1918, like this global pandemic. But, I mean - and not to say that they're the same - but the AIDS epidemic in the '80s that especially hit the gay community, I mean, people were dying right and left. I mean, gay people and people who had gay friends, I mean, lost so many people. And I'm wondering how your experience now during this pandemic is comparing to what you experienced during the AIDS epidemic and if you're drawing on anything from what you experienced through the AIDS epidemic to get through the experience now.

GUNN: Oh, I definitely. I mentioned that I really didn't come to terms with my sexuality until my early 20s. And I had only one partner, to whom I was extremely loyal and wouldn't betray, and we were very close. And he - after a long relationship, he said to me, I don't have the patience for you. And I knew he meant sexually. But I was devastated. I mean, I was in his bed watching "M*A*S*H" with him, and he said to me, I want you to leave, and this is over. And I was so devastated. I drove to my apartment. I had to pull off the road because I was hyperventilating. And this was in 1982. Oh, I forgot the important part. He told me, on the topic of not having patience with me, that he had been sleeping with dozens and dozens and dozens and dozens of other people.

So the next day was a moment of reckoning for me. And I went from being distraught and feeling worthless and just emotionally devastated to - that evolved into incredible anger because I thought he could have given me - he may have given me a death sentence. So I was - I went to my general practitioner about a month later and was tested, and I was negative, thankfully. But for the next 10 years, I was tested every six months because I thought this is living in me and it could simply appear.

And that experience has caused me to reflect upon the situation that we're in now and about how people need to wear masks. They need to social distance. They need to be rigorous and responsible about this. This is not something to be taken casually or lightly. And when our elected officials are walking around maskless in hospitals, I'm thinking this is absolutely an abhorrent message to be sending to people, that, oh, well, we don't have to do this. You could kill people, or you could be killed yourself. But in this particular case, I'm more worried about being asymptomatic and killing other people.

No, I reflect a lot about AIDS and the devastation that it wrought and my own experience with the crisis. And as I said, thankfully, nothing happened. And, you know, the man to whom I was so close for so many years, I don't know what happened to him. We never spoke again.

GROSS: Wow. God, that must've been so hard.

GUNN: Yeah, it was. It was such an awful time. And also, it was such a marginalized disease because people said, oh, well, it won't happen to normal, regular people like us; it only happens to those gay people.

GROSS: Well, you're talking about the early days of the epidemic, too...

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: ...When people were terrified...

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: ...Of going near anybody who had AIDS, and people with HIV were kind of treated like lepers. So, you know, you've talked about how, when you were young, you cried a lot. And you're moved to tears now sometimes on TV or, you know, when talking. Is it a different experience being moved to tears about something, you know, feeling tears welling up now and what it felt like to cry or what would set you off to cry as a child or adolescent?

GUNN: Oh, it's completely different, frankly. I mean, as a child, it was more about despair and frustration and angst. And now it's more about joy, frankly, and being uplifted. And in the case of my interaction with my students - but with more frequency - tearing up with the "Project Runway" designers and now with the "Making The Cut" designers, it's more about bearing witness to the triumph of the human spirit and how just reassuring that is about the quality of life and us as human beings. And it's a great honor to bear witness to that.

This happens to me at the Met all the time. I was looking at a Rembrandt painting of Flora, one of his models. And I was reading the caption and then looking at the painting again. And I had to step away because I was welling - I'm doing it now. I was just welling up with tears. It's the triumph of the human spirit. It never ceases to make me emotional. The same thing happens with reading - I mean, beautiful words. James Agee reduces me to tears quickly - many poets do. But they're just...

GROSS: How about opening overtures?

GUNN: Oh, God, yes.

GROSS: (Laughter) Yeah.

GUNN: I attended the Metropolitan Opera a little more than a year ago. "Parsifal" was playing. And I broke down during the overture, and I had to fight back tears for the next six hours. I thought, I can't make a fool of myself here. But yeah, beautiful things that pluck at my heartstrings make me tearful, and I own it. It's just part of who I am.

GROSS: My final question to you, a very important one - when you do go out and you wear a mask, what kind of mask do you have? Is it a cloth mask made out of beautiful fabric or one of those just, like, medical blue-and-white masks?

GUNN: It is a medical mask. Quite frankly, given the circumstances, I think the more medical it looks, the better. People have offered to give me fashion masks, in capital letters, and I've said, no, thank you, I have what I need and give it - give that to someone who really needs a mask right now. Also, I don't want to be thinking about, how do I tie this fashion mask into what I'm wearing? And I think it's just so much better to wear what you wear, and then you put on the medical mask because it's - has a purpose and it's serviceable, and you don't have to be thinking about vanity.

GROSS: Right. Or - yeah, making a fashion statement or something.

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: It has been such a pleasure to talk with you. I can't thank you enough for doing this. And please stay well.

GUNN: Well, Terry, I want to thank you. And it's just a pleasure speaking with you and a real honor. And I'm such a fan. And the greatest pleasure for me would be, when we get through all this pandemic stuff, to eventually meet. That would be fantastic.

GROSS: I would absolutely love that. That would be something to look forward to at the end of this (laughter). So...

GUNN: Well stay safe and be well.

GROSS: You, too.

GUNN: Thank you.

GROSS: The entire season of Tim Gunn's new fashion competition series "Making The Cut" is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

Tomorrow on FRESH AIR, we'll talk about depression and how it may be triggered by the pandemic. My guest will be humorist John Moe, whose new memoir is called "The Hilarious World Of Depression," which is also the title of his podcast in which he talks with comics, musicians and writers about their depression. His book is about his own depression. I hope you'll join us.

(SOUNDBITE OF LINDSEY TURNER'S "BEFORDTURE")

GROSS: FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham. Our interviews and reviews are produced and edited by Amy Salit, Phyllis Myers, Sam Briger, Lauren Krenzel, Heidi Saman, Therese Madden, Mooj Zadie, Thea Chaloner and Seth Kelley. Our associate producer of digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF LINDSEY TURNER'S "BEFORDTURE") Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.