Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on May 28, 2014

Transcript

May 28, 2014

Guests: John Powers - Maya Angelou

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. The Cannes Film Festival, the most important international film festival, concluded this past weekend. Getting an award at Cannes gives a new film the kind of pedigree that helps ensure good international distribution. FRESH AIR's critic-at-large, John Powers, who is also the film critic for Vogue, reported on the festival, as he's done many years.

And, as we've done several times in the past, we've invited him to tell us about the winners and the films that generated the biggest response - positive and negative. John, welcome back to FRESH AIR. And thanks for taking some time to talk with us about about Cannes. So let's start with the film that won the top prize. Tell us about it.

JOHN POWERS, BYLINE: The winner of the Palme d'Or is a Turkish film by a director named Nuri Bilge Ceylan, who's well-known internationally, not-so-well-known in the United States. And his film is a Chekhovian study of a rich, famous actor who thinks himself a very enlightened man. However, he's not so enlightened in dealing with his tenants, who are largely poor and Islamic, nor is he so enlightened in dealing with his wife and his sister - both of whom know him so well, they see through him.

And the film is basically a portrait of modern Turkey seen through these people, who all live in this posh hotel, and their dealings with the people around them. It's filled with hilariously penetrating arguments between family members who know one another so well that every line they say to one another has many, many meanings. It's a tad too long, at three hours and 15 minutes, but it's actually a very good film.

GROSS: Would you have voted for it for the top prize?

POWERS: Funny thing is - when I saw it, I wouldn't have. I was tired and jet lagged and thought this movie will never end. And yet, as the week went on, it stayed in my head very, very well. And I realized that, in fact, it probably was the best film in the competition.

GROSS: Do think it will open in the United States? Will we be able to see it?

POWERS: I think you will be able to see it. I think, you know, partly, because it won at Cannes, partly because Turkey's in the news, very interestingly. And partly because I think - what often happens with European or non-American film makers is that gradually some sort of critical mass builds up, and their films start being seen.

GROSS: So what was the hottest ticket at Cannes?

POWERS: Oh, hilariously, the hottest ticket at Cannes was for Ryan Gosling's directorial debut. And it was very funny. I was at a lunch for another movie - a Hollywood movie - and at one point, all the critics left and dashed off because we all had to go see the first feature by Ryan Gosling which turned out to be not a good film.

You realize that Ryan Gosling has seen a lot of movies and liked a lot of them. And so about every minute or two, you could identify some other famous director he was copying. So it started off a bit quick like Terrence Malick and Harmony Korine. A few minutes later, it turned into David Lynch, and then, along the way, it turned into this guy Nicolas Winding Refn, with whom Gosling has worked a lot.

And it was this big, bloody - or fake bloody - apocalyptic, crazy melodrama with bright colors and darkness and bullies and people murdering rats and all sorts of other stuff that would seem powerful if you're putting it together - and if you were David Lynch. But, in the event, everyone thought was really, really bad, and so the discussion became was this the worst film a director ever had premiered at Cannes?

GROSS: Whoa, worst ever - but you know it's funny because...

POWERS: ...Worst ever - but it wasn't.

GROSS: But, you know, last - I think it was last year - that Ryan Gosling was in a film that - as I recall, from what you said - was booed - the film "Only God Forgives?"

POWERS: Yes. No, it was booed last year. It's a very peculiar thing because Ryan Gosling - and some of the older viewers may not realize this - is a huge international star. And much beloved by women so that he is a sex symbol and a star in the way that Brad Pitt was before Brad Pitt's movies really started being big movies. Ryan Gosling is kind of in that - those early stages of super stardom. So everything he does is invested with interest. So the longest line I saw at Cannes this year was for his film. The most excited fans were for his film. And the only problem was the film wasn't very good.

GROSS: Too bad, I think he's a great actor. It's a shame.

POWERS: Oh, no. He's a great actor. And I'm really - I'm all for him. And in truth, you know, he was trying to make a genuinely great movie. And, you know, I respect that impulse more than somebody cautiously making a small, little movie that's perfectly done for their first film.

GROSS: So let's get to another prizewinner at Cannes. And this is the second place, the Grand Jury prize, that went to an Italian film called "The Wonders" by a director I have to say I've never heard of, Alice Rohrwacher. Tell us about her and of the film.

POWERS: Well, she is a young Italian director who most people have never heard of. She's only made one feature before that most people didn't see. But going into the festival, she was at highly touted to win the Palme. Then the film showed, and people didn't love it enough. And it gradually got ignored along the way, and people were even kind of mean to it. You know, the critic in variety said it didn't have enough weight to be in the competition at Cannes which was completely wrong. And then, in the end, it won second prize.

It's basically a story - a family story about a young girl whose parents have more or less dropped out of society, moved from the city to the Italian countryside where they make money by making honey by taking care of bees. And the film is about her growing up dealing with her family but also about the transformation of the Italian countryside which is becoming more and more about money and less and less about the old tradition. So it's a political film on the one hand and a personal film on the other - extremely well-made, not perfect, but very impressive work for a young director in her thirties. And, you know, I was happy to see her get the prize.

GROSS: Oh, good. So that's another one you think will come to the U.S.?

POWERS: I think it will come to the U.S. I think one of the nice things when films win big prizes at Cannes is that a film that's good, but doesn't sound commercial, will suddenly take on a commercial life. And we'll get to see it in the U.S.

GROSS: So two films tied for third place at Cannes, and that's called the Jury prize. And one of them was a film that was apparently was very divisive. Some people loved it. Some people hated it. That one was called "Mommy." And the other that tied was a Jean-Luc Godard film called "Farewell To Language." You want to start with the one that caused so much disagreement?

POWERS: Yes, you know, it's quite interesting because the two who tied - the young guy who made the film called "Mommy" is named Xavier Dolan, who's from Québec. And he's 25-years-old, and this is his fifth film. His first film played at Cannes when he was 20. And he's kind of an enfant terrible. And this film is - certainly lives up to that.

It's the story of this over-the-top working-class mom whose son is an even more over-the-top and violent boy. And essentially it's about their battles against each other, against society, against the social structure. What do you do with people who are completely out of control? It's broad. Some people think it's funny. It's extravagantly big in emotions. And when it played at Cannes, it gave people a jolt of energy that led some people, I think, to think it was better than it actually was. Coming out of it, people either thought it was brilliant or almost unwatchable. That was one of the third-place winners.

The other one was this extremely arcane, but beautiful, film by Jean-Luc Godard, the great French master, who at 84, is still probably the most radical film maker working anywhere. And it was a film about all the things that Godard likes to make movies about, which is to say, the impossibility of communicating, the beauty of images, trying to connect nature, how much fun it is to look at naked people.

GROSS: (Laughing).

POWERS: And what was so fascinating about this film, which I quite liked, was that it may be Godard's final film. And it's interesting that a person often thought to be the most intellectual and difficult film maker ever ended his film basically making the hero of this film, and his work, his dog because what he loves about dogs is that they fit into nature. They're neither conscious nor self-conscious, and they're capable of unconditional love. So after all the intellection, after all the brilliance, after all the difficult, finally, Godard is coming out on the side of being a dog.

GROSS: You know what? You don't have to write dialogue for dogs.

POWERS: You don't have to write dialogue for dogs because, as we learn from the film, dialogue doesn't really tell the truth. And in addition to all of that, the film is shot in 3-D, and partly uses 3-D to mess with our heads because normally they try to make 3-D look great. But Godard, being a radical, actually does certain moments where he superimposes two images, both in 3-D. And when the images hit, your eyes start going in different directions, and it all blurs. And your eyes almost spin in your head. And you learn something about the nature of depth perception in 3-D from watching his film because he actually plays with it in a way to show you how our vision works as well as just trying to make depth deeper in the film.

GROSS: Am I going to get a headache?

POWERS: If you watch it a little longer, you would. But the first time he did it, people were so stunned and delighted that someone was just messing with them with 3-D that the crowd spontaneously broke into applause.

GROSS: OK. So I have a confession, John. I stopped going to Godard films years ago. I loved his early work, and then I started to find his films so didactic, and yet, I still couldn't even understand what he was trying to say. So is this one good enough so that I should break my record of not going and actually go?

POWERS: I don't know that I could go that far. If you've skipped the last 20, I'm not sure that this one is enough different. But, you know, given that it may be his last one, I then think, probably, people should go just to see what it looks like when somebody is really pushing against every possible thing that one considers normal in a movie.

GROSS: Well, I'd find it interesting about his dog too. I think I'll go.

POWERS: Yes. No, and his dog is very cute - named Roxie.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is our critic-at-large, John Powers. And he was at the Cannes Film Festival which wrapped up Saturday night. And he's telling us about some of the films there. Let's take a short break, John, then we'll talk some more about Cannes. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, we're talking about the Cannes Film Festival which wrapped up Saturday night. It's the most important international film festival. And with me is our critic-at-large, John Powers, who goes to Cannes just about every year - this year being no exception. So let's get to another award at the Cannes Film Festival. And best director - that was won by Bennett Miller for his new film, "Foxcatcher." And, let's see, he also made "Capote"...

POWERS: ...And "Moneyball."

GROSS: ..."Moneyball" and a documentary called "The Cruise."

POWERS: Which is wonderful - which is quite wonderful.

GROSS: So tell us about "Foxcatcher."

POWERS: OK. "Foxcatcher" is based on a true story that, somehow, I never knew. It's the story about two Olympic wrestlers who get involved with the heir to the du Pont fortune, John E. du Pont, who decides he's going to set up a wrestling facility to help Olympic wrestlers. But it's partly his own vainglorious attempt to make himself impressive - in his own eyes, in the eyes of the world and in the eyes of his mother. And so you actually watch these more or less working-class wrestling types entering the world of the ultra rich. And then very bad things happen, as they did happen in real life - where du Pont murders one of the brothers. In - you know, for reasons that, even now, are not quite clear. Although watching the film, you start to understand some of the reasons why.

GROSS: It was a very big story in the Philadelphia and Delaware area because that's where - as I recall, he was from Delaware.

POWERS: Well, and, in fact, it's such a spectacularly interesting story. The film stars Channing Tatum, who one doesn't think of as being a very good actor, but who is very good here. It stars Mark Ruffalo who one thinks of being a good actor and who is his excellent. And Steve Carell, wearing a prosthetic nose, playing the millionaire John E. du Pont in a kind of creepy way that's unlike anything you've ever seen Steve Carell do before.

All three are good and, watching the film, you understood why Bennett Miller won the best director because he controls this complicated story. He never overemphasizes anything, and he gets really good performances from different levels of actors doing different kinds of things which then remind you that, you know, his first feature, "Capote," won Philip Seymour Hoffman the Oscar. And that his - that "Money Ball" got both Brad Pitt and Jonah Hill nominated for Oscars. And unlike many American directors, he doesn't hit everything hard. So it's a very subtle story, and he leaves you room to try to figure out yourself what's going on.

GROSS: So this is the third movie that Bennett Miller has made that's based on a real person. There was "Capote" based on Truman Capote, "Money Ball" that was based on the general manager of the Oakland A's and now this one based on John du Pont. When you see a movie like Bennett Miller's movies, do you go to the news stories or to the biography or the book afterwards and see is this an accurate depiction of what happened? And does it matter?

POWERS: Yes, I do go. You know, partly because you actually want to know what artistic choices the person made in putting things in and leaving them out. And sometimes it matters. I think that you know you're seeing something that's based on a true story, so it doesn't claim to be presenting everything exactly as it happened, and partly because there'd be no way of knowing exactly what happened, even if you were there. There'd be different points of view.

But what's interesting is that sometimes when I go back to the original source, I find that a film will be - could've been more interesting. Sometimes you find out something - a way that something has been simplified. If I can give an example from a film that everybody probably did see. In "The Social Network," for instance, Mark, the founder of Facebook, in fact, wasn't just a nerd. He belonged to the fencing team. So that - for the film, you remove that because he want him to be more nerdy in relation to the brothers - the big, athletic rowing brothers. But, in knowing that, then you decide does that make it a richer film or a poorer film?

You know, you realize that every film has to chop out some of the information that would be there. In the case of this particular film, I'm still not quite sure. It's a very interesting film. I read some details about the murder that John du Pont committed and, you know, they struck me as being really interesting. But you then realize, you might have had to put in two or three scenes extra just to get to those points, at which point, the film becomes endless. So you would naturally cut them out.

GROSS: I just always wonder why not just make a fiction film inspired by a story and not pretend like you're telling a story if you're not really going to tell the story. And again I don't mean this film in particular because I don't know how closely it adheres. But I'm always slightly bothered when the fiction version of a story - 'cause it's fictionalized in the movie - replaces the real version 'cause you don't know what's real and what's fake. So I do wonder why not just, like - why not just make it up?

POWERS: You know, I think there's probably, weirdly, a commercial reason. I mean, you know, the critic Dwight Macdonald many, many years ago wrote an essay called "The Society Of The Fact" where he talked about how Americans, in particular, were drawn to stories that were rooted in truth and facts about the real. You know, that in other countries, that's less true. And it's certainly the case that more and more Hollywood is drawn to stories that are, in one way or another, true.

You know, there are the extraordinary stories that are clearly not true about Spiderman, for instance, and the X-Men. But a lot of the so-called serious films now out of the Hollywood are anchored in true stories which maybe are thought to give gravitas. It's a way of, you know - that you can bring the people on to publicize the film and talk about the real life events around the film. In my own case, I'm like you. I'm - a friend of mine once declared me the most literal minded person he'd ever met. And so I always look at things and think - really? - why would you leave that out - but that happened? Or I look at something and think but you can't say that because now people are always going to think that this was true.

GROSS: No, exactly. And real life is always so much more complex and nuanced than the movie version. I never thought of it that there was a commercial reason.

POWERS: Yes. And you're also now competing, in this era, with reality television which claims to be real. So I think that, probably more and more, there's a generation that's being raised assuming that lots of stories are rooted in reality, and it's perfectly normal. And everybody knows you fool around with them, whereas, you know, an older person like me - not that I'm ancient, mind you - but an older person like me was used to stories that were made up most of the time. Increasingly you get stories that aren't made up.

GROSS: The best actress award this year went to Julianne Moore for her performance in a David Cronenberg film called "Maps To The Stars." And the film is an adaptation of a Bruce Wagner novel and I was really surprised to hear this because Bruce Wagner writes usually like, what, satirical films based on life in Hollywood and Cronenberg has been kind of like a non-Hollywood guy, not only because he's from Canada but also because his sensibility is really not a Hollywood sensibility.

POWERS: No it's not.

GROSS: Let's just mention some of his films so people know who he is - "A History Of Violence", "Eastern Promises."

POWERS: He made the film "Dead Ringers" and "The Fly" and "Naked Lunch." He started off making pulpier, visceral, horror movies and then gradually moved into more literary enterprises over the years. This particular one is, I guess, a poison pen letter to Hollywood in a way, in that it portrays Hollywood in all of its child abusing, self aggrandizing horror. Julianne Moore, in this particular film, plays a slightly crazy narcissistic actress whose living in the shadow of her dead, movie star mother. And she hires as her assistant a mysterious young woman played by Mia Wasikowska, who may or may not be some sort of avenging angel. And swirling around them is the fake guru therapist played by John Cusack, and the handsome limo driver played by Robert Paterson of Twilight fame. And the film is a portrait of that kind of Hollywood, but told with the kind of coldness and detachment in a way that Cronenberg often brings to things. So it's a very weird, very nastily funny film. And Julianne Moore plays, as she often does, an out-of-control person. But she does it hilariously well. Going into the film I knew she was playing that role and I thought, good heavens, I don't want to have to see Julianne Moore playing a nutty, middle-aged woman. I don't think I can handle it. But in fact she nailed the role...

GROSS: why not?

POWERS: Because I've seen - she's been doing it for 20 years. And because she's a good actress and is fearless - and because Hollywood wants you to do something, they want to do it over and over again - has been playing some version of the cracking up woman for 20 years. And because the last time I had seen her was in the film "Don Jon," the Joseph Gordon-Levitt film, where she played a sensible woman - and she was so wonderful. I thought, thank heavens she gets to go back to being just a normal human being, rather than a nut job. Here she plays a nut job, but she's so great that I wasn't surprised when she won the prize.

GROSS: John Powers will be back in the second half of the show. He's our critic at large and film critic for Vogue. Here's the Harry Lime theme from "The Third Man," the 1949 film starring Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten, which won the Grand Prix when it was shown at the Cannes festival. I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "THE THIRD MAN")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with our critic-at-large, John Powers, who's telling us about this year's Cannes Film Festival, the most important international film festival, which wrapped up over the weekend. John has reported on the festival many times for FRESH AIR and for Vogue, where he's the film critic. Were talking about some of this year's Cannes award winners. So Julianne Moore won best actress, best actor went to Timothy Spall for his role in "Mr. Turner," which is about the English painter - well, is it William Turner or J.M.W. Turner? 'Cause there's two...

POWERS: J.M.W. Turner, yes, and it's a fascinating film for two reasons. One, because Timothy Spall is really wonderful as Turner. He's a guy who's been playing supporting roles in lots and lots of films - in everything from Mike Leigh films to "Harry Potter," because he's physically not altogether prepossessing. I mean, just, he himself - when he talks about it says, oh, they've hired an ugly guy as the lead actor. And he gives this role as this vaguely uncommunicative kind of grunting man, who also happens to be a genius. It was kind of a challenging film for Mike Leigh to make, because Turner famously had one of the dullest lives of all time.

So what you're trying to do is capture the genius of an inarticulate man in a dull life, and the movie actually succeeds splendidly. Somehow you believe that he's doing these beautiful paintings. You see him in his world where he has the housekeeper who's in love with him and you and watch him enter the royal academy and compete with other painters, and you gradually get a sense of this man's world. So even though he never - Turner himself never does anything particularly interesting, Timothy Spall is so good and the stuff that Mike Leigh puts around him is so interesting that the film is generally revealing and very exciting to watch.

GROSS: So there was a another biopic at the festival, too, about Yves Saint Laurent.

POWERS: Yes, it's the second of the Yves Saint Laurent pictures. One is going to be opening in the US in June.

GROSS: Oh, so this isn't the one that I saw the trailer for?

POWERS: No, this is not the one you saw the trailer for. This is the second one. This is the unofficial one, which is interesting because the official one was allowed to use all of Yves Saint Laurent's clothing and designs. This new one is the unofficial one because it's less friendly and, therefore, the man who controls the Yves Saint Laurent estate wouldn't let them use anything, so they had to invent fake Yves Saint Laurent outfits for all the way through the movie. And, in so far as that they had to do that, they do a great job.

The interesting thing about Yves Saint Laurent is that he's one of those figures who's kind of like Warhol, where when you try to get any kind of purchase on his inner life it seems almost impossible. So rather like Turner, he's somebody who's almost impossible to penetrate. And in this particular case, with Yves Saint Laurent, the question is how do you show the world of somebody who is clearly a genius - and Saint Laurent was clearly genius - and show what he's like when he will never - almost never reveal himself? And so, we watch the people around him doing their work and that's very interesting.

There's a - one of the most brilliant scenes at the festival - maybe the single most brilliant scene at Cannes - is a scene where a middle-aged woman comes in to be dressed by Saint Laurent, and she's very shy and nervous, and he gradually makes her over, and just with a touch here and there, playing with her hair - and she's completely transformed. And you realize, oh this is what he could do and why he was worshiped. And actually, even the appeal of fashion is that you can walk in feeling kind of frumpy and not sure of yourself and walk out thinking boy, I look great and I'm full of power and glory.

GROSS: Worth seeing?

POWERS: It is worth seeing. I mean, it's slightly exasperating, but it's filled with really great stuff. I mean, it's fragmented - it is worth seeing, but, I wouldn't run there. I might walk.

GROSS: The Cannes Film Festival is, like, the most important international film festival and one of the things that makes it special - just - I can say this just from reading about it I've never been there - is that you have films from so many different cultures, representing so many different values and lifestyles, and sometimes some of the people who have made those movies have taken great risks to make the films because they come from authoritarian cultures where film is not smiled on or film that has what's considered to be some subversive values can land you in jail.

This year, the Iranian actress who starred in the Iranian film "A Separation," Leila Hatami, kissed the president of the Cannes Film Festival at the opening ceremony - apparently not a sexy kiss, but the kind of kiss you give a colleague at a festival. And this is France, where everybody says hello by kissing on both cheeks, right? So now there's an Iranian student group that's saying, this kiss is a sinful act and this actress, because she kissed a man in public, and this violates article 638 of the Islamic criminal justice code, and they want her to be flogged as stipulated by the law. What was the reaction to this at the festival?

POWERS: Oddly enough, there wasn't so much reaction to it. You somehow would've thought there would've been.

GROSS: I would've thought that.

POWERS: I mean, I can't tell whether it's simply because as we move farther and farther away from 9/11 and the various Middle Eastern wars that slipped out of people's mind, or whether now people just think every time anyone from Iran comes to Cannes, there's always some sort of trouble. You know, so, every year there's some filmmaker who has a film there for which they could be imprisoned for making, that it's now become sort of folded into the normalcy of the festival. I mean, but of course it's, you know, it's absurd to think that you would flog someone for that because this is a perfectly normal piece of behavior. It's also tricky because, you know, you're a bit under a globe when you're there. So many people work such long days.

I mean, I leave every morning at 7:30 and I often finish, you know, late at - very late at night - that you almost don't even get a chance to read the papers. And I think I am more attuned to the outer world than many of the people there. So, it's possible that, just, nobody knew much about it. When you're there you're much more likely to be overwhelmed by celebrities jetting in to promote products. The transformation of the festival is the parallel festival, which is celebrities and parties - gets bigger and bigger, and the one thing I've noticed over the years is that every year there are fewer film critics at the festival and more people who were sent only to cover parties.

GROSS: So John, how would you sum up this year's Cannes festival? Was it a good festival - lots of good films?

POWERS: It was a festival with lots of good films, but not a lot of great, you know, knock-you-out films. It's - one of the peculiarities of the film festival is, I guess, is that when you fly halfway around the world, you want to be knocked out. And so if a film is merely good, somehow you're disappointed. So that although I probably saw, you know, ten or 12 films that if, in the normalcy of my life I'd driven to a screening to see, I would have been delighted that I saw them.

Because I was jet-lagged and flung halfway around the world, I then thought this isn't quite good enough. You know, and what often happens with these films is that I then see them later, back in Los Angeles, and I think, boy was that a good film. And I think, why was I so negative about it when I saw it at Cannes? And the answer was, when you fly to Canne you're expecting masterpieces, and so you're disappointed by mere excellence.

GROSS: And you're also seeing one film after another, after another. It's a very unnatural way to see a movie.

POWERS: Yes, you know, no normal human being would see a film at 8:30, at 11, at 1, wait in line for half an hour for a three and a quarter hour Turkish film, and dash off and go to another film. And if they did it, they wouldn't expect to think, oh, I'm going to be having a good time at all of these. Whereas when you're at Cannes, you're going there and you think you're being rigorous and critical and intelligent. And what's happening is you're getting exhausted and you're getting tired of being in line and you're getting tired of talking to people the whole time, and you're getting tired of sitting. And in the midst of all of that, you then have people, like myself, making judgments that they then later think aren't true.

GROSS: You know, in following your blog post about the festival, it sounds like there were a lot of movies this year with animals, including Jean Luc Godard's new film. And also, lots of scenes of brutality towards the animals. Any pattern that's emerging here?

POWERS: When you watch animals brutalized on film, I find it almost unbearable. You know, I have ever since I was a boy. And I think, probably, most people do. I think that one reason why this year increasingly you're seeing abuse of animals in film, is that it's a way of getting pure emotion out of audiences. That it's a way of reaching audiences who are so jaded and have seen so many people murdered on-screen that they don't care. But somehow, if you actually see a cow shot down or a rabbit or in particular a dog, that plunges a dagger into your heart in a way that so many of the other things don't because - maybe because you've seen them so much or because cinema has gotten so violent toward people that now you almost don't reach people.

A couple of years ago there was a great boom in films about dead children and missing children. And that's now been replaced by terrible things happening to animals, which is, you know, a very depressing and discouraging thing to watch. I mean for several days in a row I watched some animal die awfully, onscreen. So it was a great relief by the time you got to the Jean Luc Godard film, where he was loving his dog and the film by Asia Argento, the once scandalous Italian actress who made her film about her childhood, where basically her great friend and guardian angel was her cat, Dak (PH) - a big, wonderful black cat that won the Palm d'Whiskers, which one of the critics gives every year for the best cat performance.

GROSS: John, it's always great to talk with you. Thank you so much for telling us about Cannes this year.

POWERS: Thank you for having me.

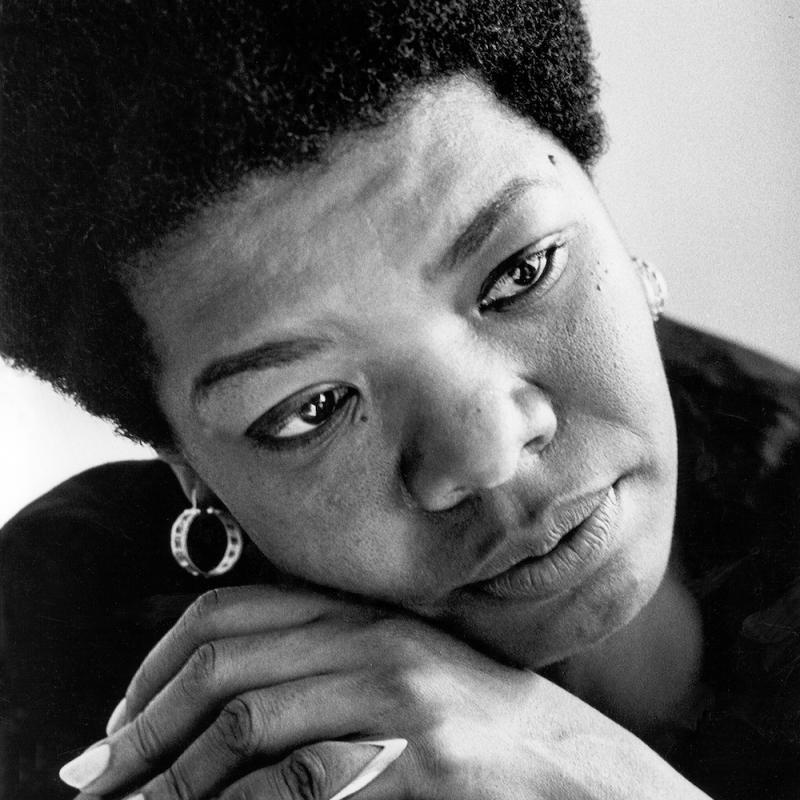

GROSS: John Powers is FRESH AIR's critic-at-large and film critic for Vogue and Vogue.com. Coming up, we listen back to a 1986 interview with writer Maya Angelou. She died today, at the age of 86. This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. Maya Angelou died today at the age of 86. We're going to listen back to an interview with her. In her six memoirs, she explored how race and gender affected her life. Her first memoir, "I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings," was published in 1969 and described growing up in the segregated South. It included the story of how Angelo was raped by her mother's boyfriend. After the rape, she withdrew into herself and went through a long period of not speaking. Maya Angelou got pregnant and became a mother when she was 16 and unmarried.

Her autobiographies described how she traveled around the country with her son Guy, earning her living as a waitress, prostitute, singer, actress and writer. In the '60s, Angelou was active in the civil rights movement and worked with Martin Luther King as the northern coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. When she was 33, she moved with her son to West Africa, yearning for the sense of home she had been unable to find in America. In 1982, she became a professor of American studies at Wake Forest University. She was the inaugural poet for Bill Clinton when he took office in 1993. In 1986, she told me that she thought her writing style was influenced by southern African-American preaching and music traditions.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

MAYA ANGELOU: I find in my poetry and prose the rhythms and imagery of the best - I mean, when I'm at my best - of the good Southern black preachers. The lyricism of the spirituals and the directness of gospel songs and the mystery of blues are in my music or in my poetry and prose or I missed everything. There's a blues - I was just thinking when I said the mystery of blues - I hadn't thought about that before. But there's a 19th century blues, which asked this question - have you ever had the blues so bad you could feel them in the palm of your hands? Now that's mystery. And that's poetry. And that's what I try for.

GROSS: Did you grow up going to church a lot...

ANGELOU: Oh, lord.

GROSS: ...And listen to a lot of blues?

ANGELOU: Oh, Lord, I went to church. My grandmother took me to church on Sunday all day long, every Sunday into the night. Then Monday evening was the missionary meeting. Tuesday evening was usher board meeting. Wednesday evening was prayer meeting. Thursday evening was visit the sick. Friday evening was chore practice. I mean, and at all those gatherings we sang. We sang long meter hymns, which are almost lost now, Terry Gross. It's a shocking, sad loss.

GROSS: What's a long meter hymn?

ANGELOU: In a long meter hymn, a singer - they call it lays out a line. And then the whole church joins in in repeating that line. And they form a wall of harmony so tight, you can't wedge a pin between it. So that a person would soon (singing) as long as I live and troubles rise, I'll hasten to his throne. Then everybody comes in. If I was there, I would sing, (singing) as long as I live. And then there are all these twists and turns and melodic accidents, harmonics and accidental harmonics which take place which just are delicious to the ear.

GROSS: Are there poems that influenced you when you were starting to write or that made you want to write?

ANGELOU: Oh, so many. There's a poem call "Sympathy" by Paul Laurence Dunbar. Mr. Dunbar wrote this about 1890. The first stanza is, I know what the caged bird feels - ah, me - when the sun is bright on the upland slopes; when the wind blows soft through the springing grass, and the river flows like a sheet of glass; when the first bird sings and the first bud opes, and the faint perfume from its chalice steals - I know what the caged bird feels.

Oh, dear. The whole poem is so beautiful. There are three versus to it.

GROSS: What else really influenced you?

ANGELOU: Well, Shakespeare - I was very influenced - still am -by Shakespeare. I couldn't believe that a white man in the 16th century could so know my heart. If he could know my heart, a black woman in the 20th century, a single parent - all the things I was ere to - then obviously I could know a Chinese Mandarin's heart and the heart of a young Jewish boy with braces on his teeth in Brooklyn.

It meant I could know - if he over those centuries could know me so that he could write, when in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone bemoan my outcast state and trouble a deaf heaven with my bootless cries and look upon myself and curse my fate, wishing me like to one more rich in hope, featured like him, like him with friends possessed and desiring this man's art, that man's scope, and with what I most enjoy contented least.

GROSS: We're listening to a 1986 interview with Maya Angelou. She died today at the age of 86. We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Maya Angelou died today at the age of 86. We are listening back to an interview I recorded with her in 1986. Her first memoir, "I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings" dealt in part with being raped when she was a child by her mother's boyfriend.

(SOUNDBITE OF NPR ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: When you were young you went through it period I think of several years of not speaking...

ANGELOU: Yes.

GROSS: Was it because of the rape?

ANGELOU: Yes.

GROSS: Do you think that you developed a sense of language through all those years of listening and not speaking? I think of the memory that you have of the facility for language that you have and all those years of not speaking - what was happening in your mind?

ANGELOU: Well I think that I thought of myself as a giant ear.

(LAUGHTER)

ANGELOU: Like something of Gary Larson which could just absorb all sound. And I would go into a room and just eat up the sound. And I memorized so many poets. I just had sheaves of poetry, still do. I would listen to the accents and I still love the way human beings sound. There is no human sound which is unbeautiful to me. And so I'm able to learn languages because I really love the way people talk.

And when I was very young, blues singers used to come walking through the sound with cigar box guitars - really a cigar box on a piece of wood and cat gut strung along it - and they'd come around the store and sing. And the fellows from the Brazos of Texas had a sound which was absolutely Texan and they'd sing (singing inaudibly). Oh, it's so gorgeous I could pull my hair out.

Then the guys who would come from Mississippi and a portion of Louisiana had another sound. They would sing, (singing) baby please don't go, baby please don't go, baby please don't go back to New Orleans, if you do where I've been, you'll seen, baby please don't go - and it was way back in the mouth, see. So I would listen, listen, just fantastic. I still get excited about any human being speaking or singing.

GROSS: Isn't it amazing how the period of being mute probably in its own way helped you to become the writer that you are?

ANGELOU: Absolutely.

GROSS: How did you start to speak again after you stopped?

ANGELOU: Well Mrs. Flowers, a lady in it in my town, a black lady, had started me to reading when I was about eight. Really reading. I was already reading but she started me to reading in the black school and I read all the books in the black school library. And she had some contact with the white school and she would bring books to me and I would just eat them up.

And when I was about eleven-and-a-half she said to me one day - I used to carry a tablet around on which I wrote answers -and she asked me, do you love poetry? So I wrote yes. It was a silly question for Mrs. Flower since she knew I just. She told me, you do not love poetry. You will never love it until you speak it. Until it comes across your tongue, through your teeth, over your lips, you will never love poetry. And I ran out of her house, I thought I'll never go back there again. She was trying to take my friend.

She came to the store and she would catch me and say you do not love poetry. Not until you speak it. And finally I did take a book of poetry and I went under the house and tried to speak. And could.

GROSS: Did you have to find your own voice after those...

ANGELOU: Oh yes, and still I mean, for years I did. I didn't even know where it was placed for that matter. And then I didn't trust it. I was afraid. And I said this before but I was afraid it might leave, you see, since I had pushed it away so long, it might on its own just take off. And then mutinous is much like any other addiction, it stands just behind my eyesight, just behind my shoulder in critical moments when a marriage ended which I thought would never end. It stands there offering itself to me saying I've got something for you - come to me.

GROSS: I'm really surprised to hear.

ANGELOU: It's true, it's terrible.

GROSS: It's tempting to not speak?

ANGELOU: Delicious.

GROSS: I guess hearing that from someone as eloquent as you makes it even harder to understand because you could use language to any effect.

ANGELOU: It's so tempting that when I'm really in bad shape I sing, sing - and my mom and my son will find me wherever I am and stay with me and see me through that period because it's there - it's saying come. I can make life so simple for you. You'll never have to explain anything again.

GROSS: When you went to Ghana, you were searching for a home but you left Ghana for about a year or so and went back to America. And you've lived where you are living now in North Carolina for a few years and you have a permanent position at a University there that you can keep as long as you want - it's a lifetime professorship. Do you feel like you have your home now? Does that really feel like home or is part of you still searching for home?

ANGELOU: No, I believe North Carolina is my home. I really believe my home is in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. I know however life offers wonderful - and by that I mean full of wonder - chances. I expect to be in Winston-Salem the rest of my life. My books are there, my paintings are there, my friends are there, and my work is there.

GROSS: Maya Angelou recorded in 1986. She died today at the age of 86 in her home in Winston-Salem.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.