A Gentler Side of Boxing.

The sport of boxing has been in the news since boxer Mike Tyson bit the ear of his opponent, Evander Holyfield. Photographer Larry Fink has captured many images of boxing which have been collected in his book, "Boxing" (Powerhouse Books). And sports writer Bert Sugar has written numerous works on sports and has served as senior vice-president of "The Ring" magazine, a magazine on boxing. He wrote the essay included in Fink's book. They'll talk about the often maligned sport. (Interview by Marty Moss-Coane)

Guests

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on August 5, 1997

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: AUGUST 05, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 080501np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: The Idol Makers

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

MARTY MOSS-COANE, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Marty Moss-Coane in for Terry Gross.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, DOCUMENTARY BY NFL FILMS)

SOUNDBITE OF FOOTBALL SCRIMMAGE

MOSS-COANE: That's the sound of a collision of football players as captured by NFL Films. They were the first to mike players and coaches, and have changed the way that sports fans have viewed and enjoyed football. The look and feel of an NFL Film is unmistakable -- reverential, larger-than-life. And its mission is clear: to glorify the sport.

In its 35 year history, NFL Films has filmed thousands of football games, boasts a sports library of more than 20 million feet of film, produced more than 3,000 TV shows and specials, and won 69 Emmys.

On August 17, the National Geographic Explorer will air their documentary on NFL Films called "The Idol Makers" on TBS.

I spoke with the president of NFL Films' Steve Sabol, son of the founder. He played football through high school and college before being hired by his father to work at the company. I asked him, when filming a game today, how big a crew he sends on the field.

STEVE SABOL, PRESIDENT AND DIRECTOR, NFL FILMS: The best way to explain that would be that live television usually uses between 12 and 15 cameras at a game. We use three, and everybody's -- see, now even you're surprised...

MOSS-COANE: I gave you that look.

SABOL: ... your eyebrows, yeah, that's right. We have three cameramen: a top man who's called a "tree" -- he's rooted into position, he gives you your basic top coverage; then we have a "mole," and he's a hand-held mobile cameraman that shoots a camera from the ground with a focal-length lens of 12 to 240, which is a fairly dramatic zoom, and once in a while, he's connected to a soundman; then we have a third cameraman who's called a "weasel" and it's his job to shoot everything but the action.

Now, when I was a cameraman, I was a weasel...

MOSS-COANE: Mm-hmm.

SABOL: ... and I shot the first 15 Super Bowls and I never saw a play, but -- because I was always shooting the coaches or the fans or some of the little details. So those are really the three elements -- the three types of cinematographers that we have at every game.

MOSS-COANE: And is that the hierarchy, with the weasel at the bottom?

SABOL: Well, I think that when people think of NFL Films, they think of the action shots. But being a former weasel myself, I think that -- actually the weasels are part of the story tellers. I was an art major in college and I remember studying Paul Cezanne, who once said that all art is selected detail.

And when we started NFL Films, I always felt there should be a cameraman that just has an eye for the details -- the cleat marks in the mud; the way the sun comes through the portals of a stadium; the silhouette of a coach walking against the sunlit stands.

And that was an element that I -- when I started to shoot -- that I focused on. So I think the weasel really is important, although certainly not as important as the guys that shoot the action.

MOSS-COANE: Are there certain cameramen you think that specialize in a certain kind of shot? Is there a guy that kind of has a "weasel" personality, that you know is just going to get those details and some of that background stuff?

SABOL: Well, when you think of NFL Films, you think well we're specialized in football. But within that specialization, there are specialists. There are cameramen that specialize just in shooting a telephoto lens; just shooting the trademark -- our ball spiraling slowly through the air.

A weasel is strictly an eye. A weasel doesn't have to know anything about football...

MOSS-COANE: Really.

SABOL: ... but nothing. I mean, at Super Bowls we usually have guest weasels. A couple years ago we had Haskell Wexler (ph), the Academy Award-winning director and DP for "Medium Cool," and he weaseled for us.

MOSS-COANE: What'd he get for you?

SABOL: He got a couple -- but it was a lot of out of focus, believe it or not, but he did -- as, you know, as you'd expect -- a cameraman of his talent, he came up with a few shots and angles that none of us, who were so immersed in the game, would have ever thought of.

MOSS-COANE: You say that your mission is to act as story tellers -- to tell the story of football or the story of a particular kind of a game. I think the language of football often is about doing battle. Is that what you think the story of football is? About warfare?

SABOL: Well, I think it's a very militaristic sport. And I think that's part of the popularity. I think it's -- you know, they always say that cultures can be defined by their games. When you look at the Greeks, they had the Olympics; the Romans had the Coliseum. And I think in a certain way now, that you can look at our society and compare it maybe to the Middle Ages, when whole towns were built around cathedrals and churches.

And now when you look at towns, there are these giant stadiums that in many ways, maybe a little bit of a stretch, that you could say that this is sort of religion now with these giant stadiums and the congregation gathers every Sunday to pay -- to worship at -- or certainly to be entertained or to draw some sort of emotional sustenance from the sport.

MOSS-COANE: Well why do you think, then, that football has really, then, supplanted baseball as the nation's pastime?

SABOL: Well, I think football is our -- I wouldn't say, Marty, it's our pastime. Football is our national passion. And I think that in many ways, it mirrors our culture. George Will had an interesting description of football. We were interviewing him for a show and he said that football is popular because it's just like our society: it's a series of committee meetings punctuated by moments of violence.

LAUGHTER

But I think there are things -- first of all, that you look at television and how that has shaped our culture. And if football hadn't been invented or hadn't evolved out of rugby 100 years ago, some time in the 1950s, a group of television executives after a six martini lunch would have gotten together and said: "what can we create that's going to draw viewers and that's going to be perfect to televise for the game -- for the television?"

And when you look at football -- the field is shaped like a television screen. And you compare it to baseball -- baseball's all geometry. It's very hard to cover baseball on television. But football is -- also has a sense of ebb and flow. It's like a good conversation. There's a play and then they regroup for the huddle and you have a chance to reflect on what you've seen.

Opposed to basketball or soccer, which is like one continuous monologue. You know, there's no chance to sit and reflect and talk about what happened, and also to talk about what's going to happen next.

So, football has this sort of conversational feel to it that's perfect for television.

MOSS-COANE: And time-out to run down for that second beer, too.

SABOL: Right -- or yes, or commercials, too.

MOSS-COANE: But do you think that you have, and the folks at NFL Films, have really then contributed to the development of the passion for this game?

SABOL: I think we have, but in sort of a naive and innocent way. I think when we started, it was four or five of us, and it was just at the time a bunch of young guys who loved to make movies, and who loved pro football and wanted to convey that love of the game to our audience.

Now, people look back at what we did and say "boy, what a -- you know, you guys were great marketers; you were great packagers; you were great promoters; what a great advertising arm."

But we never thought that way. And I still never think of NFL Films as promoting or advertising or marketing. We're just passionate observers of a sport that we all love. And in the beginning, we were allowed to do that. I mean, Pete Rozelle who was the commissioner, never told me or my father, I want you to do this, I want you to that.

In fact, and this shows you how prescient he was as a commissioner, he kept us separate from New York. He kept us -- we were from Philadelphia, and he let the company grow and evolve in Philadelphia. And he always told me and my father that it was good that way, because we would be able to take risks; that we would be separated from the corporate culture and the league, and that we could develop as filmmakers 'cause I always felt that it was important to be able to take the risk; to try new things.

And if you have to go through a series of committees, that never happens.

MOSS-COANE: And yet I know you're aware of some of the criticism that NFL Films provides a kind of propaganda...

SABOL: Oh, yeah.

MOSS-COANE: ... for the game, because it does glorify the game.

SABOL: Sure it does.

MOSS-COANE: There's no question about it.

SABOL: But in that respect, I go back to my background as an art major. There were certain artists that depicted things in a certain way, and if you wanted to show the horrors of war, Goya would be a good person to paint. If you wanted the glory of war, it could be Jeracol (ph) or Delacroix that would paint those paintings.

So we're sort of artists, but this is just our way of interpreting the way we feel about the sport. Now, if someone says "well, that's -- you're glorifying it," well, I love the game. And that's the way I feel about it.

MOSS-COANE: But we're not going to hear about drug scandals and other scandals when we watch something from NFL Films.

SABOL: No, you won't because you'll see that and you'll hear that on the networks, on the hard news. And we've never said that we are journalists. We are not journalists. We're story tellers. We're romanticists. That's what -- that's the way we've looked on ourselves, but we've never tried to convince anybody that we're journalists; that this is investigative reporting. It isn't. I mean, we still shoot film, which is a good reason. I mean, right there separates us from the electronic news media.

MOSS-COANE: Let's talk a little bit about your father, who founded NFL Films. And my understanding is that he was the home photographer...

SABOL: Oh, yeah.

MOSS-COANE: ... that if you were doing something, your dad was taking a picture of it.

SABOL: Well, my dad, first of all, to me -- I don't know how many sons can look at their father and say that they were his -- they were their hero, their father, the funniest person they ever met, the best man at my wedding, and my boss. But all of those things pertain to my father.

And NFL Films really began with a wedding present. My dad was an overcoat salesman in the 1950s, and when he was married as a wedding present, my grandmother gave him a little windup Bell and Howell movie camera. And everything that I did as his first and only son, there was my dad filming -- my first haircut, my first pony ride, my first birthday, my first football game.

And every football game that I played in, from the time I was in fourth grade to the time I graduated Haverford School in 1960, there was my dad on top of the chemistry building at Haverford School on Lancaster Avenue, filming me playing football.

So by the time I'd gotten -- I had been accepted at Colorado College, he'd gotten good enough at filming football that he felt that he was going to make this his profession. So, he dropped out of the overcoat business and took the money that he had saved up and started a film company.

And the first film that he did was called "To Catch a Whale," and they went out off Rhode Island. And not only did they not catch a whale, but my dad got really seasick and the salt water destroyed two of the cameras, so he figured that he was not going to go on the rain -- you know, he's not going to become a National Geographic. He said he'd go back to doing football.

And in 1961, the rights -- the film rights -- for the NFL Championship game had sold to an independent film producer for $1,500. And my dad decided that he would -- next year, he was going to get the rights no matter what. So he figured he would double the bid. He went to New York when they had the auction for the film rights. This is for the championship game.

He doubled the bid, $3,000, won the bid and Pete Rozelle, opening up my dad's bid -- usually in the past they'd make that, you know, they'd say well, this bid has been won by Ed Sabol and he's going to be doing the championship game.

But Peter Rozelle opened it up, saw the amount of money and then quickly read over my dad's resume and became a little concerned when he saw that his only experience filming football was filming his 14-year-old son. So he just said "Ed, I'd like to talk to you for a second." And then they went out to lunch. And after several drinks at "21," my dad and Pete came to an agreement that Peter would let my dad film the '62 championship game. That's when I got the phone call and that's when dad hired Bob Ryan (ph) and Art Spieler (ph) and Walter Dumbrow -- the three people in the company.

And that's how -- well, it was actually Blair Motion Pictures then. It was named after my sister. We didn't become NFL Films until three years later.

MOSS-COANE: So your dad was a good salesman, you're telling us.

SABOL: He had a tremendous entrepreneurial vision and he kept NFL films alive for the first four or five years. A lot of people think that our style came out of our first film. It didn't. It wasn't until 1966 when we did a film called "They Call It Pro Football" and we used a narrator by the name of John Facenda (ph) -- that that was the "Citizen Kane" of sports movies. That's when we made the break from what had been done in the past, to what I think has influenced all sports movie-making today.

MOSS-COANE: Well, I'll tell you what. We're going to take a short break and then we'll talk some more.

SABOL: OK.

MOSS-COANE: And our guest today is Steve Sabol and he's president of NFL Films. And National Geographic Explorer has done a documentary of NFL Films. It's called "Inside NFL Films" and it will air on August 17.

We'll be back after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

Our guest is Steve Sabol today, and he's president of NFL Films. Let's talk a little bit about the music, because certainly that's a very important ingredient in the making of and certainly the viewing of NFL Films -- again, to kind of heighten the drama and the experience.

What is it about that song "What Do We Do With A Drunken Sailor"...

SABOL: Oh, yeah.

MOSS-COANE: I mean, I ...

SABOL: Da da da da, da da, da, da, da, da...

MOSS-COANE: Doesn't -- hasn't that appeared several times...

SABOL: That's right. Oh, that's almost...

MOSS-COANE: ... in an NFL film.

SABOL: ... our theme song. When we started in the '60s, I felt it would be very important to develop a musical style that would be unique to football. And it wasn't the John Philip Sousa oom-pah oom-pah music, but something that was movie music -- that told a story.

And as a kid, going to Blue Mountain Camp in the Poconos, every Friday night we'd have these campfires and we'd sing these songs. And one of the songs was, you know, "what do you do with a drunken sailor, da" -- but it was one of those hummable things that you'd...

MOSS-COANE: Right.

SABOL: ... hum next day when you were playing softball or you were out canoeing. You'd be going "da, da, da, da, da, da, da..."

So when we started NFL Films, that's the kind of music I wanted, but not done with just a single instrument, but with a 50- or 60-piece orchestra. So we found this composer by the name of Sam Spence (ph) and he was working in California at the time, and we hit it off great. And I would hum some of these melodies to him, sometimes over the phone...

MOSS-COANE: These camp song melodies.

SABOL: ... camp songs, and he would -- then he would come back with 50 strings and fluegelhorns and French horns and these incredible arrangements, and it also, like John Facenda, helped create a unique style or became a signature of our movies.

MOSS-COANE: So it's possible, then, to watch some NFL Films and hunt for some camp songs that have been embedded in the sound track there.

SABOL: Oh, yeah. If you went to Blue Mountain -- yeah, you know, sure. There's a lot of...

MOSS-COANE: Kind of like "Where's Waldo?" -- NFL version of that.

SABOL: But you know, when you think of how important music is in our lives -- you get married to music; you get buried to music; you go to war to music; people make love to music. So -- and I remember watching "Gone With The Wind" that was -- what -- 222 minutes long and there's like only 19 or 20 minutes in that whole movie that doesn't have music.

And football is a sport that's -- that people associate with music. And it's so important to help build the drama and tell the story.

MOSS-COANE: So is that how you work with a composer, which is literally humming in some songs over a telephone and then they go from there?

SABOL: Well, that's how we did it -- that's how we did it for the first 15 years. Now, we have two composers, full-time composers -- Tom Headen (ph) and Dave Robideaux (ph) who work right in our NFL Films and do all the composing right there on a synthesizer and then we take their outlines on a synthesizer and then it goes over to the London Symphonic Orchestra and we do it over there.

MOSS-COANE: I wonder whether, when you look at NFL Films and you've never seen a football game, whether you have -- your expectations, then, are greater than what the game actually delivers? I was reading about a story, I think it took place in Japan...

SABOL: Yeah.

MOSS-COANE: ... where Japanese...

SABOL: Right.

MOSS-COANE: ... people had seen NFL Films before they actually saw a real live football game. They were terribly disappointed and apparently booed and hissed through all the game, looking for something that looked like NFL Films.

SABOL: Well, they thought that there would be the music.

MOSS-COANE: Right.

SABOL: They thought that they would hear the coach -- the sound of the coaches. They thought -- they didn't understand what these huddles were. They didn't see that in our film. So, they started to hiss and nobody could understand. This was in 1974 when the first NFL game was played over in Tokyo. It was the Cardinals and the Chargers.

And Dan Dierdorf, who does the Monday night broadcast, was at the game and he was the one that told the story to me. He says they were hissing and we didn't understand what it was until later an interpreter explained that they had seen these films and they wanted to know where the music was and why did it take so long and why they couldn't hear the sound. And it wasn't at all what they expected.

MOSS-COANE: So they'd rather get the film version of football...

SABOL: Right.

MOSS-COANE: ... than the real thing. Well, if you have all these archives -- all these movies in your archives -- how would you say football has changed?

SABOL: Well, I think that...

MOSS-COANE: How is it different today?

SABOL: ... it's the stadiums have changed the game because -- especially the domes. They've sterilized the game. You look at a game in the Kingdome or in the Astrodome which fortunately is not going to be used anymore. And it looks like an inside of an aquarium. The players look like little freeze-dried peas. It doesn't have the sense of grandeur and the mythic quality of the passing of the seasons that you see in the open-air stadiums.

I think that's changed. I think the players have changed in a way, in that there's a sense of entitlement now among the players -- that all this, they're entitled to. Where players in the '50s and '60s, there was a sense of gratitude; that they were privileged to be part of this -- to be part of the league; to play a game like football.

Now, there's more of a sense of, like I said, well, they're owed this. There's this entitlement. So there is a difference -- a little different, I think, feeling. And that goes back to colleges, too, because the athletes today in colleges are incredibly pampered. And that's one thing that people don't realize when you go to a -- you see how a football team operates. I mean, these players are -- every hour of the day is regimented. You eat breakfast. This is when you get dressed. Now you get in your car; you go to the bus; you go to a stadium. Back from the stadium, there's a meeting.

I mean, it's almost very similar to still being in school. So there is a certain immaturity there, and a lot of the players once they get out of the game are suddenly -- they have this incredible free, undisciplined time and it's hard to make that adjustment.

MOSS-COANE: What do you make of the die-hard football fans? I had the chance to go to a Eagles game a couple of years ago and was up -- way up in the nose-bleed section where the hard-core fans are, most of them extremely drunk. It was an extraordinary show, I will say. Lots of war paint, lots of hoopla -- you know, lots of carrying on there.

SABOL: The fans have really changed.

MOSS-COANE: What's that about, do you think?

SABOL: I don't know. You know, that's an interesting thing and we've done some pieces on that. And you could see how the fans have changed. When we started in the '60s, first of all, there was no NFL properties, so people -- you didn't have all the team identification that you have now.

And people were really into the game. But as television came along, the fan became part of the spectacle himself. And that's when you started with the "Hi Mom" and the fan shots. So then the fan came to the game not only to watch the game, but the fan felt that now he is part of this. He is part of the spectacle himself. So that's where you end up with these outrageous outfits and this whole thing where the fan now becomes part of the spectacle himself, which was different in the beginning when the fan was just a spectator.

MOSS-COANE: In this documentary about NFL Films, I think one of the cameramen says that as soon as you put a camera on a fan, their IQ drops about 20 points.

SABOL: Yeah, it's true. It's -- that was a problem that began, I think, and I'd blame Monday Night Football for that because I remember being a weasel. As a cameraman, you could go up and you could shoot a player or a fan and they would never look at the camera. They'd be involved in the game.

Then, I believe it was in 1972 -- it was a Jets game -- that one of the Jets, I believe it was Don Maynard (ph), scored a touchdown and came to the sidelines and the Monday Night cameraman came over to him and couldn't get a face shot. So the director, Chet Fordy (ph), said: "tap him on the shoulder and tell him he's on camera." So the cameraman did that. Don Maynard turned around, looked at the camera, and I guess didn't know what to do, and he said "hi, mom." And that was the beginning of the "hi, mom" syndrome which fans saw, players saw.

And from then on, it was terrible for us 'cause we couldn't get a good documentary shot because fans thought we were -- tell -- they couldn't tell the difference between two cameras.

MOSS-COANE: Right. Right.

SABOL: They'd see us, and instead of cheering or a player's -- talking about the game, they'd look at us and say "hi, mom" or you know, what they do now. And those shots are worthless to us. We can't use them.

So that was one of the more -- that was one of the bigger problems we had during the '70s and the '80s. Now, like I said, fans are part of the spectacle themselves.

MOSS-COANE: Steve Sabol is president of NFL Films. On August 17, the National Geographic Explorer airs their documentary on NFL Films, called The Idol Makers on TBS.

I'm Marty Moss-Coane and this is FRESH AIR.

Dateline: Marty Moss-Coane, Philadelphia

Guest: Steve Sabol

High: This month National Geographic Explorer will broadcast a behind-the-scenes documentary about NFL films, whose presentation of football has helped make the sport as popular as it is today. The show, which is called "Inside NFL Films: The Idol Makers," will air on August 17th at 7 PM on the TBS Superstation. Marty Moss-Coane talks with Steve Sabol, the president of NFL films, who also directs many of the NFL films.

Spec: Sports; Media; Television; TBS; National Geographic; Inside NFL Films: The Idol Makers

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: The Idol Makers

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: AUGUST 05, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 080501np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Boxing

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:30

MARTY MOSS-COANE, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Marty Moss-Coane.

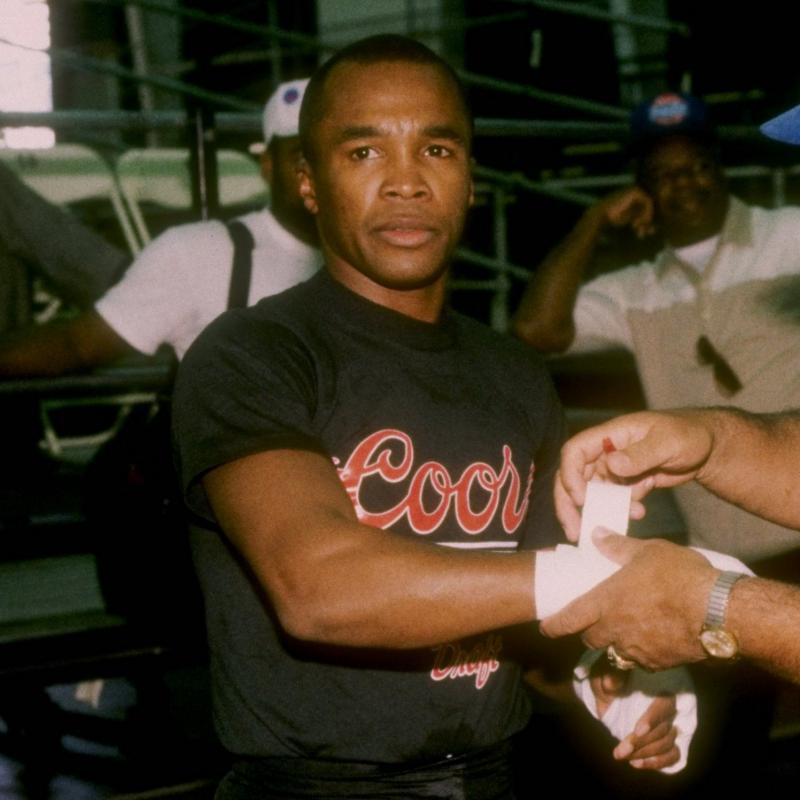

The image most of us have of boxing is a punch -- a blow to the face which contorts on impact, with blood and sweat flung through the air. It underscores the brutal violent reputation of the sport.

But photographer Larry Fink has captured a gentler side of boxing with his book of black and white photos called simply "Boxing." Fink went to training gyms, many of them in Philadelphia, and shot what goes on behind the scenes -- the hard work of training; the relationship between the boxer and trainer; the dingy settings; and the fans. An exhibit of Fink's boxing photos from the book are now at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Bert Sugar is well-known to boxing fans as a writer and commentator. He's one of the most passionate authorities on the sport and he's written an essay on the history of boxing in Larry Fink's book. They both join us today on FRESH AIR to talk about boxing.

Let's begin with Larry Fink. I asked him what got him interested in photographing boxers.

LARRY FINK, PHOTOGRAPHER, AUTHOR, "BOXING": It was a simple thing. It was just simply an assignment to photograph Jimmy Jacobs (ph), the ex-manager and so on of Mike Tyson. And it was about 11 years ago, before Tyson was champion of anything except his, you know, volatile emotions. And so it -- but it rose out of its origins and became an obsession.

MOSS-COANE: Obsession, why? How?

FINK: Why? I guess, me being right there in the cradle of all that violence and all of that contention and all that competition gave me a tremendous amount of harmony. Now why that...

MOSS-COANE: Yeah, why?

FINK: ... I can't tell you.

MOSS-COANE: Why, why that?

FINK: That probably is a deep psychological obsessive secret that I'm not about to know. Forget about tell.

MOSS-COANE: So you don't want me to ask you about that?

FINK: No, you can ask anything you'd like.

MOSS-COANE: Right. Well, let me just say I'm very struck by the contrast from the photographs that I see -- the kind of intimacy that you've been able to capture in the gym; the tenderness; the touching -- which I think does contradict and contrast what most people are familiar with with boxing, which is what you see in the ring: two guys beating each other up.

FINK: And that's what it's for and what it's about. It's about a symbolic, you know, conquest of another man's territory; to inflict some sort of doom on him. But in the gym, albeit for territorial divides and rights, there's a good deal of caring and a good deal of paternal tenderness amongst the trainer and the fighter and the various people who are part of the coterie.

It was that that really, really stimulated my interest. It was the fact that gladiators could be mothered by their own father.

MOSS-COANE: Hmm. Larry Fink, how would you describe the sounds, the smells of a boxing gym?

FINK: Well, that could be a very, very long story -- start to describe smells. But there's the smells of body which are sometimes acid and sometimes sweet. There's certainly the sound of -- there's a certain kind of gesture that they do...

SOUNDBITE OF BREATH EXHALATIONS

... when they look out to, you know, to shadow box and punch. There's a...

SOUNDBITE OF BREATH EXHALATIONS

... it's kind of a concentrating of your breath and, you know, so it becomes in alignment with your body and the striking, you know, pose of your fist.

The smells are also of the dank wood; of the spit on the floor; and of the ages and ages and ages of bad and good intentions.

MOSS-COANE: Larry Fink, when you're photographing, do you try to be invisible? If you come into a gymnasium, do you introduce yourself to some of the boxers and the trainers that are there? Or do you try to just work like a fly on the wall?

FINK: Much more hygienically so than the fly on the wall. That is no -- I...

LAUGHTER

It's a, you know, it's a rife place.

MOSS-COANE: I understand.

FINK: At any rate, I do introduce myself. I come into the gym. I mean, indeed, I'm not one of those guys who hangs around and hangs around and becomes part of the kind of the network, so I'm not a known factor.

And when I do come in, it's a special event and I do introduce myself. And many of the guys and kids who are boxing and training and stuff come up and want their picture taken in the traditional way, and I do that.

And yet, then I explain that I would rather work in a candid fashion. And then I become invisible. But the only way to become invisible in my sport of photographing is to be absolutely and utterly visible, which is to say: to photograph with real freedom, with real direction, with real drive, with utter confidence.

MOSS-COANE: What I find looking through your photographs is just this portrait of backs and shoulders and skin. We see the sweat. We see the pores -- a sensuality that I found really very touching, very moving, very beautiful.

FINK: Thank you very much.

BERT SUGAR, SPORTSWRITER, THE RING MAGAZINE: Let me say something about Larry's photos.

MOSS-COANE: Yeah, go ahead, Bert Sugar.

SUGAR: They are as untraditional as you can get, and I think that's what makes them rare. They are not "x" hitting "y" and "y's" face contorted. They're everything almost but that traditional -- and I don't say "classic," 'cause I think Larry's are; they aren't -- traditional photo of the hitting.

These are everything in and around and leading up to, but it is the people and as you pointed out very aptly, the sensuality of these people in this sport -- this machismatic sport -- who are, I think, the interest and what really is Larry's forte.

MOSS-COANE: Larry, did you study anatomy, for instance?

FINK: Over long years of looking at bodies.

MOSS-COANE: Yeah.

LAUGHTER

MOSS-COANE: Informal training. But is that...

FINK: I have no formal training whatsoever.

MOSS-COANE: ... but do you find yourself, then, attract -- is that what you see? The sort of slope of a shoulder; the sort of catch of a face?

FINK: Yeah. I mean, I'm either blessed or cursed with a vision which is all too physical.

MOSS-COANE: And black and white seems very appropriate for photographs about boxing. Larry?

FINK: Well, one of the things about the -- many of the pictures in the book and the whole Philadelphia boxing scene is that the venues in which they take place are -- look a little bit like 1940, 1950. The "Blue Horizon" is a thing out of the past, even though it's still working into the future. And the gyms are the same.

And black and white, of course, is appropriate to that kind of high drama; the idea that there's victories to be won and defeats to be suffered. You know, that all things, you know, aren't relative. That there are absolutes in life. Black and white is, indeed, symbolically black and white.

MOSS-COANE: I want to talk a little bit more about the relationship between the boxer and the trainer. And Larry Fink, you said what you saw were fathers mothering these young men. I mean, that's the kind of, I guess, outsider looking at this relationship. What does it mean when a father mothers a boxer?

FINK: Well, in our culture, very, very often, men don't have the license to touch one another. And somehow or another, when guys put on gloves, first of all, they can't even go to the bathroom by themselves, so they have to be cared for by the men who surround them and who wipe down their ears and get the sweat off their face and so on and so forth.

So what it does is it -- it brings to bear a new license of physical immersion, if you will. So the mothering is just simply touching.

SUGAR: If I may, Marty.

MOSS-COANE: Go ahead, Bert Sugar. Yeah.

SUGAR: ... it's Bert again. You'll excuse the pun or two-thirds of a pun -- PU -- that in talking about touching, there is a touching act at the end of boxing that you ever see -- never see in other sports, with maybe the exception after the final Stanley Cup game, where they line up all the hockey players and they shake hands.

There is more hugging and appreciation by boxers who have fought each other in the ring after they've just taken all these rounds to try to do whatever they can and beat the bejabbers out of each other...

MOSS-COANE: You say box...

SUGAR: ... than I have ever seen in any sport.

MOSS-COANE: Boxers hugging boxers.

SUGAR: After 10 rounds or 12 rounds or how many rounds it is, hugging each other in appreciation and respect for what they have stood for, and as long as they've stood.

FINK: Over and over again, it happens. It's really -- it's a real act of majesty.

MOSS-COANE: An act of majesty?

FINK: Yeah.

MOSS-COANE: And -- to go from this combat, then, to this very caring, tender affection.

SUGAR: And an appreciation of another person, which is rare in sports where everything seems dominated by a seek and destroy approach, no matter what the sport.

MOSS-COANE: My guests are photographer Larry Fink and sportswriter Bert Sugar. We'll be back after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

Well, we're talking about boxing today and our guests are photographer Larry Fink, and he has a book of photographs called Boxing. And in that book is an essay by Bert Sugar, a boxing commentator, has written many, many books about boxing and a former editor of Ring magazine and Boxing Illustrated.

Reading your essay, Bert Sugar, about boxing and looking some at the history and looking some at the sociology, it is a lens, I think, to understand certain parts of this country's history. Certainly, it's an urban sport -- one that has, I guess, took root and really stayed in cities. Right?

SUGAR: In the main, that's right, Marty. There are exceptions, but those exceptions more than anything make the rules. It's kids who were raised in very crowded atmospheres; had to fight for survival; fight for their way out; fight for pride; fight for territory -- turf, as Larry said; anything.

Going all the way back to the Irish tenements in the 1840s; through the ghettos of the early Jewish settlers of the first decade of the 20th century; to the Italians; the African-Americans, then called Blacks in the now projects; the Latinos in the barrios -- whatever, they had to do this to survive and in many cases were able to translate and channel this into boxing itself.

MOSS-COANE: And do you think boxing is a way of, then, and I guess I'm speaking metaphorically here, though -- a way of fighting your way into society? And thinking about these various immigrant groups, they all had their boxing champs who fought for them.

SUGAR: Fought for them; fought for their pride; fought for their identification and they all vicariously and -- not every Irish man fought, but they identified with John L. Sullivan; and not every Jewish immigrant on the Lower East Side fought, but they identified with Benny Leonard (ph); and the Italians with Rocky Marciano; and the blacks with Joe Louis; and the Latinos with Roberto Duran and others.

It's a -- you know, he's theirs. He's their symbol. And through his success, their success grows. It's a major thing in the growth of this country.

MOSS-COANE: Has a boxer, perhaps even a good boxer, ever come from the upper classes?

SUGAR: The closest -- and I was asked that recently -- the closest that we can ever, I mean there have been -- Anthony Biddle Duke fought Philadelphia Jack O'Brien and got his head handed to him in sparring matches. I mean, boxing does not get its recruits at the debutante line at the country club.

But there have been borderline middle class kids -- Gene Tunney having been one. He studied Shakespeare. And you know what? The fight crowd didn't appreciate him because he was not one of them. These kids are scrappers. They're scrapping for a piece of life; a piece of success; a piece, if you will, of history, even momentary history, by being called "champion."

And it's a wonderful thing to see. But upper class, no, let them play polo, is the thought.

LAUGHTER

MOSS-COANE: Well, Larry Fink, is that also what interests you in boxing, because it's about, perhaps, class struggle? It's about racial and ethnic issues which are still very raw today. Do you see that?

FINK: Extremely raw.

MOSS-COANE: I mean, do you see that?

FINK: I -- yeah, I mean, my -- I have a slight political history in this of -- about class struggle. And certainly the underclass moving its way up through its fist, through individuated victories is certainly part of my interest, for sure, you know.

MOSS-COANE: Because you've also taken photographs of society people.

FINK: Oh, yeah. Over the year, I mean, a long time ago, I was on this program with a book called "Social Graces" which was a group of pictures from rural Pennsylvania, real working class pithy, you know, funky-types. And then people from the debutante balls, not the boxing recruits, though.

So I've always -- my work has always been involved with aspects of power and how it doesn't actually fulfill you, even though you think it might.

MOSS-COANE: Well, it's interesting, Larry Fink, to think about, I guess, the power of the fist in boxing and the kind of economic/political/social power associated with the upper classes. How do you photograph that? What's the visual difference?

FINK: The visual difference is profound. I mean, the boxers are half naked. They're full of their bodies. They're full of a certain kind of sensuality and thrust, and they're full of a primary individuated kind of, you know, competitiveness.

Whereas in the Wall Street, in the debutantes, there's a tremendous amount of tittering and self-consciousness and vanity of a different order -- where people are much more prone to neurotic tremulos than, you know, basic fisticuffs.

SUGAR: Boxing, if I may just jump in...

MOSS-COANE: Go ahead, Bert Sugar.

SUGAR: ... why boxing appeals to me is in this era of homogenization, where everything is big business and big this and big that, one of the last -- really, one of the last refuge of individual entrepreneurialship and individualism is boxing. It's boxing. This is a single sport by a single man against another single man. It's not one of 11 or one of nine or one of five in the world of sports. Or one of millions getting downsized in that big firm in the sky.

This is one man, and he's going to make his way as one man.

FINK: The family farm.

MOSS-COANE: Well, let's talk a little bit about the Mike Tyson-Evander Holyfield fight of this past July in Las Vegas. The Nevada State Athletic Commission revoked Tyson's license. He can apparently apply for it within a year's time, and they fined him some $3 million.

Bert Sugar, in your book, is this enough punishment for what he did in that boxing ring, which is to bite part of Holyfield's ear off?

SUGAR: No. This man should not ever be allowed to fight again. He brings the sport into disrepute. He brings human behavior into -- he shames it. Why it really hurts me, Marty, is the people who are against boxing -- who view it as pure savagery anyway, and I disagree with them, but there is -- they have the rights to their thoughts -- cannot distinguish between what Mike Tyson did and what those kids who learned to operate within the rules have done. This man should be barred, period, and a paragraph from sports from now on.

MOSS-COANE: What kind of a boxer would you say, looking at Tyson's career -- and he's won, I don't know, more than $100 million in the years that he's been boxing -- what kind of a boxer is he? Where do you put him, Bert Sugar?

SUGAR: Well, I wrote the book "The Hundred Greatest Boxers of All Time" and I didn't put him in it before this. So he would have fallen out by definition before this. He wasn't in it, so I don't have to do an arrangement and a rearrangement.

MOSS-COANE: But why do you think he's done so well, if he's, in your book, not that good a boxer?

SUGAR: Well, remember boxing goes back, as my essay in Larry's book shows you, for 100 years. So 100 boxers -- 100 greatest boxers is like writing on the head of a pin The Lord's Prayer -- you have to tuck in a lot.

So Mike Tyson has only -- see, a great boxer fights other great boxers. There's a rub off here. Muhammad Ali is a great boxer. He's a great boxer as much for his skills as for having fought and beaten men like George Foreman; for having fought and beaten men like Joe Frasier; for having fought and beaten men like Ken Norton. And you can make a case in each of their instances, they're great.

Mike Tyson, in 35 fights, has fought one man who maybe had a passing chance at greatness, and that was Michael Spinx, and that was nine years ago. He has not rubbed off against other greatness, and I really don't see it, and that was his greatest fight, and it was nine years ago.

Mike Tyson, I thought, had a chance and had skills when the aforementioned Jimmy Jacobs was managing him. They now are non-evident. His skills are so far behind him they're in a rear-view mirror and he can barely see them. And I just don't think he's one of the great boxers of all time.

MOSS-COANE: Why do you think he's so well-known?

FINK: Well, he was very, very strong and he was very, very mighty. And also, Jimmy Jacobs and the club down there perpetuated that sense of "Iron Mike," you know.

SUGAR: And take that one step further, he also has transcended the sports page to the tabloid front page.

FINK: Yeah, he got himself involved with all kinds of malarkey, as we know now.

SUGAR: Malarkey called "rape." Malarkey called "auto wrecks." Malarkey called "assaulting people on streets." Malarkey called "giving away his car once he dented a fender." He's -- and marriage to Robin Givens and whatever and whatever.

So, Mike Tyson is sort of a celebrity sighting more than a fighter.

MOSS-COANE: But he is part of this tradition that you write about, Bert Sugar, which is a kid in trouble; grows up in a poor neighborhood; gets "adopted" by somebody who wants to -- sees, obviously, some kind of gift there and wants to shape them, then, for the ring. What do you think went wrong with Mike Tyson?

SUGAR: I think he was apologized for throughout life and never had to accept responsibility, which is not only a growing up process for everybody, and boxers are included in "everybody." But I think he somehow managed to avoid that. Cus D'Amato (ph), a great, great, great trainer was the man who adopted him, if you will, and took him out of a juvenile delinquency home and promised to have him graduate high school. He didn't.

He would continue to get him out of trouble. He would continue to side with him. Jimmy Jacobs, who was a lovely gentle person, acknowledged that if it wasn't -- that if he hadn't had Mike fighting up to 20 times a year, he'd always be in trouble. He had to pay to get him out of a jam in Los Angeles, where he assaulted a valet in a parking lot who was trying to come to the aid of some girl that Mike was assaulting.

He -- he's that bad seed. He's the Patty Duke that I -- you know, you have to see to know what the other kids have done to right their lives.

FINK: On the other hand of that, though...

MOSS-COANE: Go ahead, Larry Fink.

FINK: ... my experience with Tyson, which is very, very, very limited...

SUGAR: And was a long time ago.

FINK: And was a long time ago, because I saw him way before he was, you know, doused by the flame of championship and money -- was that he was a developing young human being. I mean, Cus, while he apologized for him had a sense of ethic -- a sense of a pathway for him. And Cus' usual thing was to try to make men out of boxers, as well as gladiators.

But Mike was definitely a much more volatile property than anybody could handle. And indeed, the mothering became indulging and the indulging, of course, you know, got in the way of the kid's real growth.

MOSS-COANE: Larry Fink's new book of photographs of boxers is called Boxing. Sportswriter Bert Sugar has a boxing essay in that book. We'll talk more about the sport in one minute.

This is FRESH AIR.

Let's continue our conversation with boxing photographer Larry Fink and boxing writer Bert Sugar.

This is a mostly male sport. What do you think, Bert Sugar, about the emergence of women boxers? Do you like that? Is it good for the sport?

SUGAR: I think it's probably very good for the sport.

MOSS-COANE: Do you like to watch it?

SUGAR: No. I must tell you. I have nothing against the rights of women to box, anymore than I have anything against the rights of men to strip at Chippendale's. I also have my rights not to watch either of them.

MOSS-COANE: Well, why don't you like to watch it?

SUGAR: 'Cause I saw the best fight ever with Marlene Dietrich in "Destry Rides Again." They'll never beat that one. I don't know. It's always been a, to me, and I'm a traditionalist...

MOSS-COANE: OK.

SUGAR: ... I love the -- I have nothing against women's basketball. It think it's balletic. I think that's a wonderful thing. But I have something against women hitting each other. I just don't think that that's what I was raised in the South to be about.

MOSS-COANE: Not very lady-like, I guess.

SUGAR: I think that's probably the easiest way of saying it. And I do feel, you know, and I -- there are women, by-the-by, all over this country who go to gyms to take the regimen, and it's a hard regimen of boxing, to stay in shape. But not to get hit in the nose. You know, even back to Heidelberg in the old Shishmarks (ph), they didn't -- to have them wear it doesn't endear them any more than seeing a woman trucker with "Mom" tattooed on her arm.

MOSS-COANE: Oh, dear, Bert Sugar. Let me turn to you, Larry Fink. Have you photographed women boxing?

FINK: A little bit, yeah.

MOSS-COANE: What do you think?

FINK: Well, actually I agree with Bert when it comes to the match. I mean, I've -- I once again have photographed them mostly in the gyms working out, doing the regime, and, indeed, that's, you know, an awesome-looking thing because here's these women, and they're pounding the hell out of these bags and guttering and, you know, spewing all over the place and what not. It's not very feminine.

LAUGHTER

But then again, they can do what -- you know, anybody can do what they want to do as long as they don't hurt others.

SUGAR: I guess, Marty, in passing, you said: "is women boxing good for boxing?" Ironically, yes, because if you remember women are becoming bigger and bigger, if you will, viewers of sports. The last Olympics, 55 percent of those watching were women. And I think this might be a way of refreshening and regenerating the sport by women boxers and women who identify with them. Not for me, but for the sport.

MOSS-COANE: What do you make of the fans, Larry Fink? And they certainly -- you have photographs in them -- they're watching very carefully and then there are moments when, of course, they're exploding with either delight or horror. What's the kind of texture you get from them? What do they bring to the game? The sport?

FINK: Well, since I'm in the front row, most of the texture that I get is sort of steamy and projectiles, you know...

SUGAR: I've seen Larry. He always looks like a Sunday School teacher turning around, looking like he's waiting for the next spit ball to hit him.

FINK: Really -- one-eyed Larry here. But what I make of them, I mean, it depends on what section of the gym you go into, whether it be the lawyers or the street thugs, on what kind of, you know, delivery that they give you, the photographer. But the photographer being in the front row, a fine artist of some repute, you know, some kind of reputation, has no reputation whatsoever to a fight fan, who says "down in front" and when they say it, they mean it and you better get down.

LAUGHTER

SUGAR: I've seen that act. This -- while they are, and I think there is more, if you will, comradeship amongst boxing fans, even if you're on the other side of the coin from them, and you think "x" is going to win and they think "y" is going to win, you're sharing more with them than I ever have at anything except a college football game.

There is a camaraderie there. You're there to see a fight, and you are talking to them. And I enjoy these people and no, I'm not taking them home for dinner, but yes, I am taking them to the corner pub to analyze a fight because that is our milieu and that's where we met and that's what we have in common.

FINK: You know it's interesting: in traveling around the country as a photographer, I'll be in airports for only-too-long periods of time, and I'll see a guy with a boxing magazine and I'll go up to him, or -- and we'll start talking. And immediately, we have a kind of fraternity which is unusual to this world. It's -- for me, it's brought an entirely new vista into my life.

MOSS-COANE: I want to thank both of you so much for joining us today on the show. I'm sorry we're out of time. Thank you very much.

SUGAR: Thank you, Marty.

FINK: Thank you.

MOSS-COANE: Larry Fink has a new book of photographs called Boxing. An exhibit of these photos is at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York through September 7. Bert Sugar is a leading authority on boxing and has an essay in Larry Fink's book.

Dateline: Marty Moss-Coane, Philadelphia

Guest: Larry Fink; Bert Sugar

High: The sport of boxing has been in the news since boxer Mike Tyson bit the ear of his opponent, Evander Holyfield. Photographer Larry Fink has captured many images of boxing which have been collected in his book, "Boxing." And sports writer Bert Sugar has written numerous works on sports and has served as senior vice-president of The Ring magazine, a magazine on boxing. He wrote the essay included in Fink's book. They'll talk about the often maligned sport.

Spec: Sports; Boxing; Media; Photography

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Boxing

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.