Other segments from the episode on January 21, 2019

Transcript

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

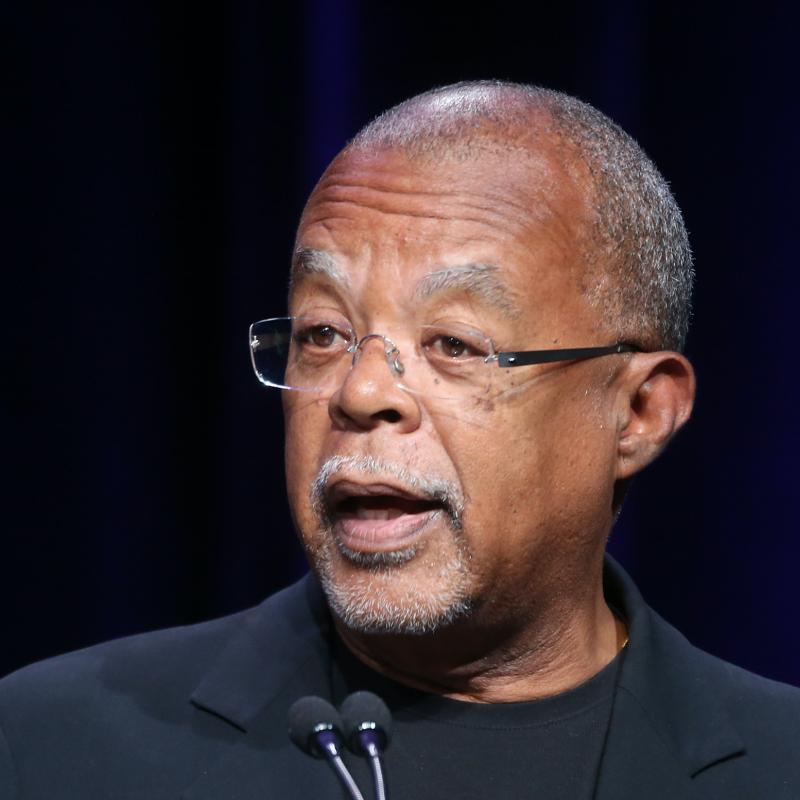

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies in for Terry Gross. As we honor the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King today, we're going to listen to an interview Terry recorded with historian Henry Louis Gates. The new season of his TV series "Finding Your Roots" is now showing on PBS. In the show, notable guests discover their family roots based on genealogical research and DNA results. This kind of research has been especially important for African-Americans whose ancestors had their names and families taken away when they were enslaved. One episode this season explores Gates' own DNA and family history.

Professor Gates is the director of the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Research at Harvard and has produced numerous books and documentaries about African-American history. Terry spoke to Henry Louis Gates in front of an audience last May when he was in Philadelphia to receive WHYY's annual Lifelong Learning Award.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

HENRY LOUIS GATES: Thank you.

TERRY GROSS, BYLINE: Because you've talked to everybody about their genealogy, I want to talk with you about yours and what you've learned about yourself and the larger meaning of what you've learned about yourself. And I want to start with the person who got you started in genealogy. It was really, like, the photograph of her - of your great-great-aunt Jane Gates. And you've...

GATES: Great-great-grandma.

GROSS: Great-great-grandma, I mean.

GATES: Yes.

GROSS: Yeah. Thank you. So I want to read something that you wrote about her. And you got this from the 1870 census - (reading) that Jane Gates, age 51, female, mulatto, laundress and nurse, owns real estate valued at $1,400; born in Maryland; cannot read or write. Now she was born in 1819; died in 1888. You were 9 years old when you found her picture.

GATES: Right.

GROSS: And you got this information from the 1870 census. So reading this - that she's a mulatto; she'd been a slave - the first question that comes to my mind - and I don't know if it was the first question that came to yours - was, was she raped by the man who owned her?

GATES: I can't believe you asked this question because...

GROSS: Is that too personal? It's a horrible way to start, in a way.

GATES: Well, the average African-American...

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: The average African-American is 24 percent European. Now think about that. And most DNA companies in the United States will tell you that they have never tested an African-American who is 100 percent from sub-Saharan Africa. This is called an admixture test. It measures your ancestry back 500 years approximately. So what that means is that it's the percent of - if you had a perfect family tree, what percent would be from sub-Saharan Africa? What percent would be from Europe? What percent would be Native American?

African-American - I love to joke about this. African-Americans all think that they're a descendant from a Native American. And the average African-American has less than 1 percent Native American ancestry, but they have 24 percent European ancestry. So where does that come from? It comes from slavery. Was this an equal sexual relationship? Of course not. So obviously rape or, at best, cajoled sexuality was the cause, but there are exceptions. When I did Morgan Freeman's family tree, it was obvious through his DNA that he was descended from a white man who was an overseer on a plantation in Mississippi. And we knew the name of his great-great-grandmother and the name of this white man. So overseer, slave plantation - rape, right? Except in the next scene, I showed him their headstones. They were buried next to each other. As soon as the Civil War ended, they became common law husband and wife...

GROSS: Wow.

GATES: ...Which was illegal in Mississippi. They lived together. They had kids, and they're buried next to each other.

GROSS: OK. So let's get back to your great-great-grandmother.

GATES: OK.

GROSS: So you assume it was not a consensual relationship, but she managed to own her own home five years after being freed from slavery.

GATES: For which she paid cash. So you...

GROSS: How do you do that?

GATES: Because of this white man. You don't get $1,400 by saving your nickels and dimes as a slave, right?

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: So obviously somebody gave her that money. She paid cash for that house in what was largely a white neighborhood. And our family - my cousin, Johnny Gates (ph), still owns that house to this day. It was just put on the historic...

GROSS: That's amazing.

GATES: ...Register in Maryland. Isn't that a cool thing? But I saw that photograph and read her obituary on the day that we buried my father's father, Edward St. Lawrence Gates. And the obituary said, died this day in Cumberland, Md., January 6, 1888; Aunt Jane Gates, an estimable colored woman. And that night - and then daddy showed my brother and me, Dr. Paul Gates now, chief of dentistry at Bronx-Lebanon Hospital...

GROSS: Very impressive.

GATES: Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: Well, it's the spirit of my mother. I could've won the Nobel Prize, and somebody would say congratulations. My mother would say, tell them about your brother who's a dentist.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: I go, yeah, I got a brother who's a dentist, you know? OK. So we went - my father showed us that picture and that obituary, and we went home. And the last thing I did before I went to bed was - we always had a desk in our bedrooms and had a bookcase. And on my desk set a red Webster's dictionary. Kids don't even know what they are anymore, but everybody here does. And the last thing I did before I went to bed on July 2, 1960, was to look up the word estimable. And that imprinted this woman's story in my mind. And the only reason that I started making the series that became "Finding Your Roots" is because of that obituary and that photograph. So I'm telling this story over and over of my - of rediscovering my own lost roots. And the geneticists have found the identity finally of Jane Gates's paramour, the man...

GROSS: Oh, really?

GATES: Yes. My great-great-grandfather's now been found.

GROSS: And who is he?

GATES: We know he was Irish from my DNA. I have the Ui Neil Haplotype. You get your Y DNA from your father, and that's what makes me a man. And you don't have a Y DNA, so that's why you're a woman. And my Y DNA, which is - comes in an unbroken chain, descends from this Irishman. So we knew he was Irish. Yeah.

GROSS: OK. On your mother's side, you found out that you had three men in the family who were freed slaves - freed before 1776. And they fought in the Revolutionary War. And consequently, you are now a member of the Sons of the American Revolution.

GATES: Yeah, isn't that a hoot?

GROSS: It's amazing.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: My...

(CROSSTALK)

GATES: And, you know, what's even more amazing, it's - one, it was my mother's third great grandfather - my fourth great grandfather. His name was John Redman. And he fought in - for the Continental Army. He was a free negro, as we would have said then. And he mustered in in Winchester, Va., on Christmas Day, 1778, and was mustered down the Continental Army in April of 1784. It's the damnedest thing I ever heard. And what's the real showstopper for me is the fact that my three sets of my fourth great grandparents lived 18 miles from where I was born. I don't think that's true for very many people in this room or any - or many people who are watching this show. It's incredible that the mystery to my family tree - I'm looking toward Africa, and it was 18 miles away in Moorefield, W.Va., County Courthouse.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: That's incredible.

GROSS: That's really interesting. Yeah.

GATES: It's really interesting.

GROSS: But when I think about your ancestors fighting in the Revolutionary War and then...

GATES: Just one. John Redman.

GROSS: Just one. OK.

GATES: Yeah.

GROSS: And then your slightly more contemporary ancestors not having any rights in the country, you know, or very few rights - not being able to vote, having to live in segregation. It's just - when you think about American history...

GATES: It's mind-boggling.

GROSS: ...It's mind-boggling. I mean, like, my - I'm second-generation American.

GATES: Oh, you are?

GROSS: Yeah. And when my grandparents came as immigrants, my family was able to assimilate pretty easily because we're white. You know, and your family was, one of them anyways, was in the Revolutionary War.

GATES: And think about it. They - but you're absolutely right. Even if you were free and you were black...

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: ...In most states, you weren't allowed to vote. In some states - like, New York would let them vote sometimes, and then take it away. And then it was a property requirement. It was a horrible, horrible thing. It was better to be free than be a slave, but you were free but not free.

GROSS: OK. So you found out that your ancestors were, like, 18 miles away from where you lived.

GATES: Yeah.

GROSS: But you also wanted to know who were your African ancestors.

GATES: Yeah.

GROSS: So when you had your DNA done, did you have a wish for a certain area of Africa or a certain group of African people who you wanted to be your ancestors?

GATES: Yeah. No one's ever asked me that, but the answer's yes because I studied with a person who has been on your show, Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian playwright, when I went to the University of Cambridge. He was there in exile because he had been in prison and to be offering civil war for 27 months and was given a fellowship at the University of Cambridge. And I showed up from Yale, and he became my mentor. And so he introduced me to the Yoruba people. You know, we used to say tribe, but now that's not politically correct - so the Yoruba ethnic group in Western Nigeria. And I wanted to be from them. But when I started the series, it wasn't called "Finding Your Roots." If you remember, it was called "African-American Lives." I only did black people.

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: I did an episode with Oprah and Quincy Jones and Bishop T.D. Jakes and Chris Tucker. And the DNA tests we were doing at that time - when they analyzed my Y DNA, it went to Ireland. And when they analyzed my mitochondrial DNA, it went to England. I am descended from - on my father's side - from a white man who impregnated a black woman and, on my mother's side, from a white woman who was impregnated by a black man.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: So if you were a Martian and came down to look at my DNA results, you'd think I was a white boy, you know?

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: And then when they did my admixture, I'm 50 percent sub-Saharan African and 50 percent European and virtually no Native American ancestry, which really pisses my family off.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: admixture, I'm 50 percent sub-Saharan African and 50 percent European and virtually no Native American ancestry, which really pisses my family off.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So you're not Yoruba.

GATES: But then they did another special test. And I cluster more toward the Yoruba than any - because 50 percent...

GROSS: Oh, OK.

GATES: ...Of my ancestry is from sub-Saharan Africa. But it's just not those two genetic lines.

DAVIES: Henry Louis Gates speaking with Terry Gross in May of last year. We'll hear more after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONNY ROLLINS' "SKYLARK")

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. And we're listening to Terry's interview with Henry Louis Gates. They spoke in front of an audience last May when Gates received WHYY's annual Lifelong Learning Award. The fifth season of Gates' TV series "Finding Your Roots" is now running on PBS. When we left off, Gates was talking about his own DNA mix. Testing showed he had ancestors from sub-Saharan Africa, Ireland and England.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: So given this kind of really rich mix that you've just described and all the surprises that you've just described, what does race mean to you? What is race? Does race exist?

GATES: No. Race is a social construction. But mutations exist. Biology matters. When my daughters were born, I had them tested for sickle cell because - black people are not the only people in the world that have sickle cell. But we have a disproportionately higher risk of sickle cell. You might have prostate cancer that runs in your family. You might have breast cancer. We know that BRCA1, BRCA2 - they're genetic. And if you're Ashkenazi Jewish, you might have a higher risk for those kind of things or Tay-Sachs. You can say on the one hand that race is a social construction. But on the other hand, you can't say that biology doesn't matter because it does matter. So I just wrote an essay that was published by Yale University Press about race. And the title is Race Is A Social Construction, But Mutations Are Real" (ph).

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: But race is...

GROSS: Have you been medically DNA tested?

GATES: Huh?

GROSS: Do you know - do you want to know your medical DNA?

GATES: Oh, my father and I were the first father and son of any race and the first African-Americans fully sequenced. In 2009, when I did "Faces Of America," a retail value of full genomic sequencing was $300,000.

GROSS: Whoa.

GATES: And because it was PBS, we negotiated a deal with this company Illumina which sequences everybody. For $50,000, they sequenced my father, me and then 12 of the guests who were in "Faces Of America" - not a full genome but a dense genotyping. So that was a steal. Now you can get a full sequence for less than $5,000 - some people say $1,000 or $2,000. That's how much the science of genetics has changed in terms of the retail market since 2009. It's incredible.

GROSS: So you know your medical background and if you're...

GATES: Yeah. Well, I'll tell you a funny story. I told them that I did not want to know if I had any of the sort of - I don't know - the slam-dunk genes for Alzheimer's disease.

GROSS: Right. Right.

GATES: And they said, OK, we won't tell you. And so then they came in - this is a big deal back in 2008. And we filmed the whole thing. They had two geneticists. They had a medical doctor who specializes in sharing this information. They flew him in from San Francisco. And another person to interpret my genetic data because it's 6 billion base pairs, right? It's a lot of data to process. And I sat down. We started to roll. And the first thing they said was, you don't have any of the genes that's going to give you Alzheimer's.

GROSS: (Laughter).

GATES: I said, thank God. Thank God. Thank God.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: And my father lived to be 97 1/2 without any dementia. So I thought that I had a pretty good chance. So what I did - my father and I agreed, for science, that we'd put our genomes in the public domain so that any scholar or student can study our genome. So I'm out there.

GROSS: Right, right.

GATES: You know, I'm totally exposed. That's the way it is.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So having done your, like, ancestry and everything, were you close to your parents?

GATES: Was I close to them?

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: Very close to them, yeah, particularly to my mother. When I was a boy, I was closer to my mother than my father. When I became a teenager, my father and I bonded. My father loved sports, and I didn't care about sports that much. I was more of a bookworm. And when I was a young teenager, early adolescence, my father and I connected through the news. He loved the news. And I loved the news. And my brother went off to dental school. So it was just the two of us and my mom, right?

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: That was one of the happiest days of my life when my brother went to dental school.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: He wasn't even out the door, and I moved into his bedroom. I go, goodbye. I hope you never come back, you know?

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: Maybe for Christmas, OK, that's fine (laughter). So then I became close to them but in two completely different ways.

GROSS: Your father died not too long ago - a few years ago. He was 97, as you said.

GATES: Yeah.

GROSS: Because you knew so much about your family history and because the day you got interested in your family history was the day your grandfather died...

GATES: Right.

GROSS: ...Was that reflected in the way you wanted to say goodbye to your father at the funeral?

GATES: Yeah. You know, I try to - doing "Finding Your Roots" is a way to paying homage to my mother and father every year. It's - remember, it's - my father dragged my brother and me upstairs in his parents' home and made us wait why he'd look through half a dozen of his father's scrapbooks, about which we knew nothing - complete mystery, a secret to us - looking for that obituary. And it's for my father. It's a gift - and for my mom. And it turned out - my father used to say, you know, your mother's family is really distinguished, too? And I couldn't imagine what, but two sets of those fourth great-grandparents are from my mother's line.

And my mother used to write the eulogies, the obituaries for all the black people in the Potomac Valley, where I grew up. And they would be published in the newspaper. And then when we go - when you were buried, she would stand up. The minister would call on her. And she would stand up and read their obituary, their eulogy. And before I started school - I started school when I was, well, 5, turning 6 - I would get dressed up, and I would go to church with my mom. And I would watch this beautiful, brilliant goddess. My mother was a seamstress, as you know. And your father was a tailor, which is why we...

GROSS: My grandfather, yeah.

GATES: Your grandfather.

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: And my mother went to Atlantic City. And we have a wall of degrees at home. And I have my mother's certificate from this vocational school where she learned to be a seamstress. And she was a beautiful woman. And I realized only recently that though I was raised to be a doctor, deep down, I really wanted to be a writer. And the reason I wanted to be a writer is that my mother wrote so beautifully and read so beautifully. So my whole life is really an attempt to honor and please my parents and make them proud of me, you know. And I hope they are.

GROSS: But it's making me think of how much death figured into your formative thoughts - the death of your grandfather, which led you to see the picture of your great-great-grandmother, everybody's deaths through your mother memorialized in those obituaries.

GATES: That's true. So you're saying I should have been an undertaker. There we go.

GROSS: Yeah. That's...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That was my next question. Yeah.

GATES: (Laughter).

GROSS: (Laughter) So I want to change the subject a little bit. People might remember the Beer Summit, when you were stopped in your own home trying to unjam a lock after a long trip. And your driver was helping you - well, he was shoving his shoulder against the door trying to open it.

GATES: Yeah, he knocked the door down.

GROSS: He knocked it down. OK.

GATES: Yeah. Right.

GROSS: And it was reported as if it was a break-in, and a police officer came and arrested you.

GATES: He arrested me. Yes, he did.

GROSS: Huge story. And it really kind of deepened the racial divide in America, with everybody taking sides because...

GATES: For two...

GROSS: ...The officer was white.

GATES: For two weeks. Yeah. Right.

GROSS: OK, for two weeks. But then President Obama called you both together. And he, and you, the officer and Joe Biden sat down, had a beer or two. It's called the Beer Summit.

GATES: Right.

GROSS: And I read you talking about this. You said that after - you had been getting death threats and these angry emails and everything. After that, everything stopped.

GATES: Right after the Beer Summit, it all went away.

GROSS: And it made me think about - because I was just reading this - it made me think about how a president can set the tone for the country on so many things, including, you know, racial issues, immigration. I think you know where I'm heading here. So (laughter) given the example that President Obama set in calming down that kind of argument in America over you and this officer, what do you hear now coming from our president?

GATES: Well, I was on "The View." And one of the, you know, wonderful people on "The View" said did I think that Donald Trump is racist. I said, well, I've never met Donald Trump. And I think that we throw terms like that around too loosely. So I would say, you know, no, I don't think so. I have a couple black friends - I went to Yale with Ben Carson and with Ben's wife. I mean, they know Donald Trump. Armstrong Williams, a person I really admire and like, I ask him, and he said absolutely not.

But I think that Donald Trump's rhetoric and some of his actions - for instance, after Charlottesville - encourage unfavorable race relations in the United States. And I think that that's sad. And I don't think that he understands how much power that - to heal, to bind that the Oval Office metaphorically has. Barack Obama understood that and, I think, certainly helped our nation to heal.

But on the other hand, Terry, there were a lot of people who never forgave the country for electing a black man to the White House. And there were a lot of people who voted for Donald Trump as a repudiation vote. And I was shocked by that. Remember all the talk about post-racialism that...

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: ...We thought when Obama - we had turned a corner, and we could, you know, beat our - the plowshares into pruning hooks - right? - like the Bible says? That's not the way it was.

DAVIES: Henry Louis Gates spoke with Terry Gross before a live audience in Philadelphia last May. After a break, he'll talk about his childhood and about how DNA evidence demonstrates there's no such thing as racial purity. Also, journalist Brian Palmer talks about how slavery and the Civil War are described at Confederate historic sites in the South. I'm Dave Davies This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, in for Terry Gross. We're listening to the interview Terry recorded with Harvard historian, author and filmmaker Henry Louis Gates before an audience at WHYY in Philadelphia last May. The new season of Gates' TV series "Finding Your Roots" is now running on PBS.

GROSS: There's some people who are trying to use genealogy to out people who are white supremacists and say, oh, you think you're so pure white, that that's such a big deal?

GATES: Right.

GROSS: Let's look at your ancestry and see who's really in it.

GATES: Right.

GROSS: And it's a way of outing people as not being who they think they are and not recognizing that we're all descended from so many different people. But the ancestry is being investigated against the will of the people being outed. What do you think of that?

GATES: Well, I think that you should have the right to - you have to ask someone. You have to get permission. The only reason people...

GROSS: I think they're doing it through records and not through, like, secretly getting their blood samples.

GATES: Oh. No, but it - or...

GROSS: (Laughter) But - yeah.

GATES: Now, we don't do blood anymore, right? We'd spit in a test tube.

GROSS: Oh. Oh, right. Right, right.

GATES: But everyone who's in one of those databases has given some kind of permission.

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: Otherwise they wouldn't be in a database. But I think that you should have to get permission before someone is creeping around in your DNA.

GROSS: Right. Right.

GATES: Don't you? But I think that one of the mottos of finding your roots is that there is no such thing as racial purity, that these people who have fantasies, these white supremacists, of this Aryan brotherhood, you know, this Aryan heritage that is pure and unsullied and untainted, that they're living in a dream world. It doesn't exist. We're all admixed. You know, no matter how different we appear phenotypically, under the skin we're 99.99 percent the same. And that is the lesson of "Finding Your Roots."

The lesson of "Finding Your Roots" - we're all immigrants. Black people came here - not willingly, of course. They came in slave ships. But they came from someplace else. Even the Native Americans came from someplace else about 16,000 years ago. So everybody who showed up on this continent is from someplace else. And under the skin, we are almost identical genetically. And that is the strongest argument for brotherhood, sisterhood and the unity of the human species. And I make it every week over and over with "Finding Your Roots."

(APPLAUSE)

GROSS: So I want to squeeze in one more question.

GATES: Sure.

GROSS: When you were 14, you had a football injury. And I don't know if that ruined your sports career forever, but it affected your leg forever.

GATES: My sports career was ruined before...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: I've interviewed many people over the years. And I've learned that a lot of artists and writers and scholars, at some period in their life, were sick or physically laid up for an injury or...

GATES: Oh, interesting.

GROSS: Yeah. And they stayed home, and they read. Or they stayed home, and they drew. Or they stayed home, and they listened to or played music. And I'm wondering if being laid up from an injury for a while affected your desire to - and your time to immerse yourself in books.

GATES: I was bookish from the beginning.

GROSS: Were you?

GATES: Yeah, I loved books. My mother used to read me - the greatest book ever written to me was "The Poky Little Puppy," right?

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: And I gave it to my mother once. I found the first edition when I was an adult. And I gave it to her for birthday. And she burst into tears because she used to read me that book all the time. And my father would just make up stories and tell my brother and me. But I was in traction for - six weeks in traction when I was...

GROSS: Whoa. That's a long time when you're young.

GATES: Yeah, I was 15 years old. And that is a long time. And by in traction, I mean on my back with my foot up with weights.

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: They don't do that anymore for this particular kind of - I had a broken hip. It was just misdiagnosed. And...

GROSS: You had a broken hip?

GATES: Yeah. And I was in the hospital for six weeks. And it's just crazy. And a doctor from the Philippines taught me to play chess at West Virginia University Medical Center in Morgantown, W.Va. And he'd come around in rounds. And we'd have the chess board set up. And he'd make a couple - a move. Then he'd come back. And then he'd - and I read quite a lot. But I also watched TV. And TV was on kind of like the hearth in New England.

GROSS: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

GATES: Our TV - when we woke up, the TV was on, and nobody ever turned it off until you went to sleep. And I watched reruns of early black films like "Amos 'n' Andy" and "Beulah." All that was on still in 1965 in syndication. And I learned a lot about the medium. And deep down, I realized in retrospect that my desire to make films was probably born about that time.

GROSS: Did you watch old movies on TV?

GATES: Yeah, I loved them.

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: And we - they only put - remember "The Late Show"?

GROSS: Oh, yeah.

GATES: And then there was "The Late Late Show." And at the time, the airwaves were so segregated, they only put black films on "The Late Late Show." And then black people would tell each other - they would say, you know, be sure to watch "The Late Late Show" tonight because "Imitation Of Life," which is my favorite film - 1934, with Claudette Colbert. And when this little girl's passing for - she passes for white and breaks her mother's heart. And she come to - it's the woman who invents box pancake mix - right? - like the Aunt Jemima figure. And she's the cook for Claudette Colbert. And she and Claudette Colbert are both unmarried mothers. And she invents this pancake mix, and they become fabulously wealthy. And the black woman says all she wants is enough money to have a New Orleans-type funeral. So everybody knew that this whole thing was building to the climax when Delilah - is her name - the character. And she dies of a broken heart because her little girl passes for white and goes off - and never sees her again.

And you - the last scene is the funeral. And they have a horse-drawn carriage. It's beautiful. And they got the brothers in uniforms with swords and stuff coming out of the church with this sad, black church music. And then you see this white girl next to Claudette Colbert. And you realize it's Peola, grown up, coming back. And she throws herself on the casket. Mama - I'm sorry, Mama. I killed my mama. And at this point, I'd run over to my mother and say, Mama, I'll never pass for white, Mama.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: I'll never - I love you, Mama. I love you. I love you being black. I'm going to be black.

GROSS: But you had family that passed for white.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: You had family that passed for white.

GATES: Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

GATES: The Gateses all looked - my father looked white.

GROSS: I saw his picture in the obituary. He looked white.

GATES: Yeah, yeah. And my grandfather was so white, we called him Casper behind his back.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: But I have an announcement to make...

GROSS: Yes.

GATES: ...For you. In front of all these people and all these viewers. I'm here to ask, on behalf of our production staff, if you will be a guest in next season...

GROSS: Oh, you're kidding (laughter).

GATES: ...Of "Finding Your Roots." Yeah. Would you do it?

GROSS: Yeah.

(APPLAUSE)

GATES: OK.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: Got you.

GROSS: All right.

(LAUGHTER)

GATES: She can't even talk.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: I can't - stunned.

GATES: Terry Gross speechless - first time in 35 years.

GROSS: Totally stunned. I regret we are out of time.

GATES: OK. I can do it. This is FRESH AIR.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: It has been a great honor to speak with you. Thank you so much for accepting this award. And...

GATES: Thank you.

GROSS: ...Thank you for all of all of the things you've written for your TV shows, for your movies. Thank you for being you.

GATES: Thank you, darling. Thank you.

(APPLAUSE)

GATES: Salt and pepper (laughter).

GROSS: Terry Gross interviewed Henry Louis Gates last May when he was in Philadelphia to accept the WHYY Lifelong Learning Award. Gates is the host of the TV genealogy series "Finding Your Roots." Terry will be one of the guests whose family history is explored next year in the sixth season of the show. The fifth season of "Finding Your Roots" is currently showing on PBS. Coming up, journalist Brian Palmer talks about how slavery and the Civil War are described at Confederate historic sites in the South. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ALLEN TOUSSAINT'S "EGYPTIAN FANTASY") Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.