Historian Tyler Anbinder

He writes about the Five Points neighborhood in Lower Manhattan which is the setting of Martin Scorsese's new film. Anbinder's book is Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood that Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections and Became the World's Most Notorious Slum. Anbinder is an associate professor of history at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on January 27, 2003

Transcript

DATE January 27, 2003 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Martin Scorsese discusses the making of his new

film, "Gangs of New York"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

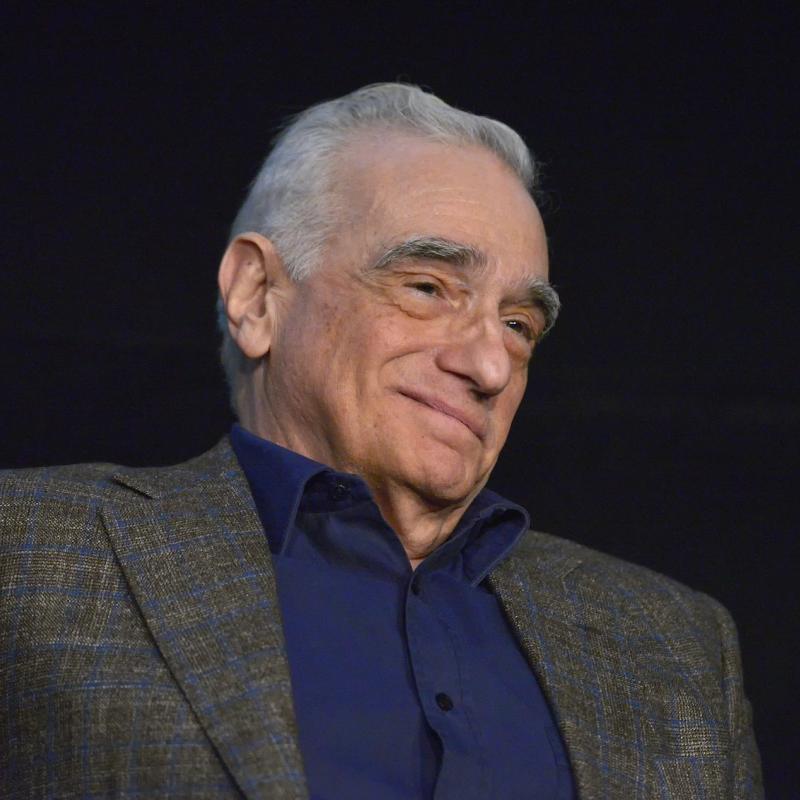

My guest, Martin Scorsese, grew up in Manhattan's Little Italy, a few blocks

from the neighborhood that was once called Five Points, the place where his

new movie, "Gangs of New York," is set. He first started working on the film

in 1978. A little later, we'll hear from historian Tyler Anbinder, who has

written a history of Five Points, the 19th-century neighborhood of immigrants

which became famous for its abject poverty, filthy tenements, garbage-covered

streets, prostitution and violence.

Last week, Scorsese won a Golden Globe for best director. His film "Gangs of

New York" focuses on the conflict between two gangs in Five Points, the Irish

and the Natives, Anglo-Saxons who were born in New York and think the new

immigrants are polluting it. Leonardo DiCaprio is one of the leaders of the

Irish gang; Daniel Day-Lewis plays the leader of the Natives. He killed

DiCaprio's father.

DiCaprio grows up in reform school. In this scene, he has just been released

and has returned to Five Points. His friend, played by Henry Thomas, is

filling him in on the latest developments there.

(Soundbite from "Gangs of New York")

Mr. HENRY THOMAS: You got the Daybreak Boys and the Swamp Angels. They work

the river looting ships. The Frog Hollows shanghai sailors down around the

Bloody Angle. Shirt Tails was rough for a while, but they've become a bunch

of jack-rolling dandies, lolling around Murderers' Alley looking like

Chinamen. Hellcat Maggie, she tried to open her own grog shop, but she drunk

up all her own liquor and got throwed out on the street. Now she's on the

(unintelligible). There's the Plug Uglies--they're from somewhere deep in

the Old Country, got their own language; no one understands what they're

saying. They love to fight the cops. And the nightwalkers and rag pickers

They're so scurvy, only the Plug Uglies'll talk to them, but who knows what

they're saying? The Slaughterhousers and the Broadway Twisters, they're a

fine bunch of bingo boys. And the Little Forty Thieves. I used to run with

them for a while, till they got took over by Benjer the Cockroach(ph) and his

red-eyed buggers. Benjer carries a germ. If you try to leave the gang, they

say he hacks up blood on you.

GROSS: I asked Martin Scorsese to share some of his impressions of Five

Points.

Mr. MARTIN SCORSESE (Director, "Gangs of New York"): The area of the Five

Points really reflected the breakdown of civilization that--many tried to keep

a family together, but many of them were not given jobs and they would just

disintegrate, so to speak, the families, into drunkenness and all kinds of

terrible situations that occurred down there. That place was maybe 40,000

people living in a very small area, sort of like the Wild West in a way,

except that instead of wide-open spaces, you've got everything somewhat

claustrophobic, everybody crowded around each other and on top of each other.

So what I'm getting at is that besides the sense of the Irish family, there's

something even more primal, which is, first of all, survival, and once that

person gets some food and then feeds the family, the next thing is shelter,

and the next thing is gathering with other families to form a tribe. And this

is what I was going for. It was almost like a post-apocalyptic world, where

people had to redefine what living really is, let alone get into politics, not

even get into that area.

GROSS: The opening scene in "Gangs of New York" is a battle scene in 1846

between Irish immigrants and the men calling themselves Natives because they

were born in America. Liam Neeson leads the Irish gang; Daniel Day-Lewis

leads the Natives. We first see the Irish gang getting ready for this battle

in this enormous underground--like a huge tunnel.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: What is this tunnel?

Mr. SCORSESE: Well, the thing is, let me put it this way. The film is not

historical documentary.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: The idea was--the film's an opera. People who are quibbling

about whether a cave exists or not--I'm telling you--you tell me--you can

argue me in terms of people have argued me about it. `Well, was there a

cave?' Yes, there are caves. Have you ever gone down in a tenement to

turn--when the fuse goes off? On Elizabeth Street in 1955, when the fuses

went out and you have to go down to the basement to put a new fuse in, first

of all, you had to be armed, because of the rats, and you found below there

were more--I think what they did, you see--I know that the Italians used the

subbasements--not just the basement, but the subbasements for storage, but

mainly for making wine, which was very important. I do know, and I actually

saw it happen, that some basements have so many kind of--How should I put

it?--secret ways, a person who was a thief, let's say, or somebody's chasing

him or her, they go into a basement on Mulberry Street and come out on

Elizabeth, somehow, or come out in the back yards down by the church.

This was all done for protection, and I think very importantly, the idea was

to at times, make the film feel as if you were witnessing a sort of fevered

dream that these people come right from the bowels of the Earth, that they

represent every group that's ever been oppressed and every group that's ever

been part of the dispossessed.

GROSS: I figure also saying you're a longtime Manhattan resident, and you

can't imagine New York without undergrounds of various sorts.

Mr. SCORSESE: It's true.

GROSS: The sewer system, the subway, the basements...

Mr. SCORSESE: The sewers alone, I mean...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: I can't even get into what that must look like down there, and

I've been below. I mean, go to the Chinese area. I tell you now that there

are places below the ground where people are working--way below the ground.

GROSS: Well, this opening fight sequence is kind of amazing. It looks almost

medieval, because, you know, people are--partially because of how they're

dressed and how it's shot.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes. Well, they have to scare the other person that's, you

know, basically screaming and they're wearing...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: ...fearsome makeup...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: ...and body paint and all sorts of things. Anybody does--they

still do today in battle.

GROSS: And they're fighting with knives and with cleavers...

Mr. SCORSESE: Right.

GROSS: And in this fight sequence, particularly like Daniel Day-Lewis, who

plays a butcher and a gang leader...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes. Yes.

GROSS: ...he's walking around with this huge cleaver...

Mr. SCORSESE: That's right.

GROSS: ...just kind of hacking away at people's legs...

Mr. SCORSESE: Absolutely, yes.

GROSS: And it's gruesome. And I'm remembering back to a previous interview

that you recorded on FRESH AIR, you had...

Mr. SCORSESE: Ah, but we didn't say it was graphic, though, like...

GROSS: No, no, no, no, but I'm interested why you wanted to make it not

graphic.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah. Because I made so many films over the years that deal

with violence in a pretty flat, straightforward way. I just didn't know how

else to do it except the way I did it in "Mean Streets" and "Taxi Driver" and

"GoodFellas" and "Casino." But by the end of "Casino," the killing of Joe

Pesci and his brother and the string of killings in Las Vegas, in my mind, I

think, you know, it's very important to depict this lifestyle, and you have to

show the downside, and this is the downside of it.

And you have to be honest with it. I just think you have to be honest in the

portrayal of violence, to not glorify it, but just put yourself in that

position and to understand the brutality of it and particularly the killing,

let's say, of Pesci and his brother at that point, by his best friends, simply

with baseball bats. The brutality is primeval, you know, and I think--I don't

want to make it stylish anymore, but I didn't want to fall into a cause and

effect of violent movement and you see the effect, graphically. I wanted to

suggest it with camera moves, camera speed--48 frames, 64 frames, 12 frames,

speeding up and down, starting a shot at 48, going to 12, then going to 24,

back and forth, reverse it, that sort of stuff--and also through sound

effects, but very little sound effects, so that I wanted to stylize,

particularly the opening battle scene, based on--well, of course you know

there's Orson Welles' the best battle scene ever in the film, "Chimes of

Midnight," and films--I just enjoy watching the Russian cinema of the 1920s,

Petovkin(ph), particularly Eisenstein, Rodchenko and a number of others.

And so certain--there was one instance in "Potemkin" that I saw that was

interesting. Again, I--naturally, everybody knows "Potemkin" and particularly

the Odessa Steps sequence, but I always remembered the scene where the sailor

is washing dishes, and he comes to a dish that says, `Give us this day our

daily bread' on the dish, and the scene before had shown that they were

feeding the sailors rotten meat, and the sailors were about to mutiny because

of this, and he was washing this dish, he's wearing a striped T-shirt, and he

just looks at the dish, and it cuts back to his face, looks at the dish, and

then he smashes the dish, and I think maybe in the smashing of the dish,

there's maybe 12 cuts, but the cuts I was interested in were the cuts on his

arm, elbow, having had completed the motion of the breaking of the dish, the

power in his arm, but it was after the action and so this gave me an idea of

different aspects of different parts of--let me put it this way, stunt moves,

battle moves. In other words, I was more interested in not necessarily

showing the...

GROSS: The knife going into the wound, yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah, exactly, but I also wasn't that interested--I mean,

basically, if it was all hand-to-hand combat, it...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: ...it should be done in another way. In other words, there was

no big surprise. The big surprise, ultimately, is when Bill the Butcher

finally finds his way to Priest Vallon. That's the surprise. Everything

else, I was interested in the movement, the movement and the creation of a

kind of confused, futile, primeval world, everything--just the futility of the

fight itself. You add to that the music that we put on that--it was a piece

by Peter Gabriel called "Signal to Noise," which is pretty interesting--and I

think you got a sense of what I was trying.

GROSS: Yet now that music is pretty contemporary, and the scene...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: ...takes place in 1846, but as you were saying, it looks more

medieval...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...than 19th-century, so why use contemporary music?

Mr. SCORSESE: Well, I didn't want to be--there's no reason to be kind of

literal. I didn't want to be literal at all in the movie. Originally, back

in 1979 when I wanted to make the film, but I really didn't make a serious

attempt to make the film at that time, but I had envisioned The Clash doing

the music, and the three boys there at the time being in the film in some way

or another, and it was going to be even more contemporary, the music, but in

this case I didn't want to make it literal at all. There are times when I do

go--throughout the picture, all the--How should I put it?--source music, in a

way, is very, very accurate, as much as possible. Sometimes it may slip into

blues a little too soon for the period, you know, just a little, but I

couldn't help it.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: I couldn't help it, because it was happening. That was the

idea. It was all coming together, so every now and then, we slip in a little

something. But in terms of the Gabriel piece at that point, it's more like a

dirge, more like an elegy, in a way, the scene, rather than a battle scene.

GROSS: My guest is Martin Scorsese. We're talking about his new film, "Gangs

of New York." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Martin Scorsese, and we're talking about his new movie,

"Gangs of New York."

Now in addition to that opening fight sequence that we're talking about,

there's a long and fascinating series of fight sequences at the end of the

film...

Mr. SCORSESE: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: ...as part of the draft riots, and these are the riots after the first

draft in the Union was created during the Civil War...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: ...when 25,000 men from New York City alone were going to be drafted,

so there were riots throughout Manhattan, and even...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: ...even the military is coming in with cannons firing onto the city.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: And you're showing that. Now it's not exactly a cast of thousands

epic, you know, like "Spartacus" or something, but this is pretty big battle

scenes. I'm reminded of, when you were talking about "The Last Temptation of

Christ" and you were complaining...

Mr. SCORSESE: Uh-huh.

GROSS: ...that it was such a cheap film...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah.

GROSS: You had like four extras, and you had to keep moving around.

Mr. SCORSESE: Well, I panned the camera. It was the same four guys

constantly.

GROSS: Exactly. Exactly. So here you are, working with actually a lot of

extras...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...in these battle sequences. Are there things you had to learn how

to do, that you hadn't done before...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes. Communicate.

GROSS: ...to choreograph these scenes? Yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: Communicate, basically. Let them all know what you wanted, you

know? But again, I had a very strong second unit director, Vic Armstrong, who

really helped me a great deal. A lot of the fight scenes in the beginning of

the film, and particularly the ending at one point, these were shots that were

drawn on paper and then they were actually drawn in an edited order. Shot one

would go to shot two, two to three, three to four, four shots, and I designed

it in such a way--and I gave those shots, while I was doing other stuff,

because we controlled the whole area, you see. We had all those sets that

were our sets. It was our little city. Vic Armstrong was able to go off and

literally get me those frames.

But at the end, we handled that battle scene differently. And it was a matter

of the explosions in the square and ultimately the Union troops coming in, and

those wide shots, which we did in a more traditional way, I think, with six or

seven cameras, and then we found quickly that, although we knew it, that

howitzer shells exploding in the square would hit the dust, and people would

just find themselves locked in some limbo, just dust and white smoke all

around them. And so we utilized that to isolate Bill and Amsterdam, and that

went on and on like that, so I was very much helped by Vic Armstrong, and also

Joe Reidy and Michael Hausman and all these people who helped put this scene

together. In fact, the big fight scene at the end was--the biggest shots were

done only in one day.

GROSS: Wow.

Mr. SCORSESE: The detail stuff went on for a couple of weeks. That was

stronger. But you know, this was a period the Union troops did have to come

in and--to make it even more interesting in a way--I never was able to get

this in the picture; I tried a few times, but there's so many things I had to

sort of limit myself. I wanted to do so much with it. But the troops did

come in from after having won the battle of Gettysburg, and so, you know, this

was a major issue. I mean, they were hard-bitten troops and they had just

gone through hell, and it was the first major battle, I think, that began to

turn the war towards the North. And they were using howitzers in the streets.

GROSS: Daniel Day-Lewis plays Bill the Butcher. He's literally a butcher,

but he's metaphorically a butcher, too. He's the leader of this gang of

Natives, and he runs around with this cleaver, butchering people...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah, not all the time.

GROSS: Well, not all the time, but...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah. Just when it...

GROSS: ...enough of the time, and he seems to get a great deal of pleasure

from it as well.

Mr. SCORSESE: He enjoys it, yes. Yes.

GROSS: Anyways, it's quite a performance. The last time you directed Daniel

Day-Lewis, it was in a very reserved performance in your film...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: ..."The Age of Innocence." Can you describe at all what you told him

you wanted from him in this movie, and how you worked with him on his

performance?

Mr. SCORSESE: Well, I think, you know, what it was, was that we got to know

each other somewhat in "Age of Innocence," and he became Newland Archer in

"Age of Innocence," and so we were able to talk, and I sort of felt a bond

with him, and then of course, I'd seen him in "My Left Foot," and then after

"Age of Innocence," I saw him in "In the Name of the Father" and films like

that, and of course, "The Last of the Mohicans," so I knew he was capable of

the other side of Newland Archer, let's say, and the key thing was to convince

him to be in the film, and that was done by myself and Leo DiCaprio and Harvey

Weinstein in New York. And ultimately I think what I was really hoping for,

and I think we got, is a man of that period, a man who's a warlord of that

period, let's say.

And many of these men were ex-pugilists--most of them were--ex-fighters,

butchers, whatever. The butcher was looked upon by the working class and the

lower classes as a sort of king of merchants in a way, and so he already had

some power going in as a showman. And this was what I wanted, the theater

piece, the showman, the man who, as he later says, conducts--Or how should I

put it?--commits fearsome acts, with a sense of theatricality and a sense of

humor, a charismatic leader, and this is what I wanted. And I knew that he

would be able to find that, although with him, he had pointed out--last week

we were talking--he pointed out that usually the character has to find him,

has to let himself be known to him, and so he just becomes--after about two or

three weeks, you find that whatever moves he's making, suggestions for an

improv or something, is coming from the character, who's now sort of

permeating his being, in a way.

So when he talks to you, and when he talked to me like off-camera, or just

even on the telephone, it's no longer as Daniel, and it's not some magical

process. It just happens to be the way he goes through it, and I...

GROSS: But he starts talking to you as Bill the Butcher?

Mr. SCORSESE: Oh, constantly, so even if it's a telephone on the holidays, at

dinner, and sometimes would make comments, particularly when he was in costume

and off-camera, he was definitely Bill, and comment about the--of course, you

know, Daniel's Irish, but he would comment about the Irish, make comments

about them on the set, stir up trouble that way to keep the energy going.

GROSS: Well, how do you respond to that, though, when you know somebody's

talking to you in persona, and it's in fact...

Mr. SCORSESE: It's easier.

GROSS: ...a persona you created. It's easier?

Mr. SCORSESE: Oh, much easier. Much easier.

GROSS: What do you mean?

Mr. SCORSESE: You're dealing with the real thing. You're just going, `OK,

Bill, what do you think of this?' `Well, if he did that to me, I would have

to do this.' `I see, uh-huh. True, but what if he went this way?' And I

mean, it goes on, it goes back and forth. It's actually cutting out a

middleman.

GROSS: Oh...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah, it's cutting out Daniel.

GROSS: ...that's funny.

Mr. SCORSESE: It's going straight to Bill. It was fine with me.

GROSS: Yeah, but what if he starts talking to you about like the weather as

Bill the Butcher, or, you know...

Mr. SCORSESE: That's what he did.

GROSS: Yeah?

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah. That's OK.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah.

GROSS: Anybody else you've worked with do that?

Mr. SCORSESE: A couple of people, yeah. To a certain extent. I don't think

as much as I encountered with Newland and Bill, let me put it that way.

GROSS: And his accent--where does that come from?

Mr. SCORSESE: Well, we started working on the accents--Tim Monich is our

dialect coach, you know, from "Age of Innocence" on all my movies. And Tim

got together with me, and we did some research with Bill--I mean, with Daniel.

And one of the first things he found was, of course, there's no recordings.

There's a lot written in colloquial New Yorkese, so to speak--these plays on

the Bowery about the Bowery Boys in the 1840s, and 1850s, 1860s. There's a

lot in the written page. We see the way the words are written. Boys is

B-H-O-O-Y-S or something. I might be wrong about that. But Tugalese Mag(ph)

and the names and the names of the people. And, of course, the jargon, or I

should say the--they really had their own language. It was called the

rogue's--it was written up in 1859 by an ex-police chief into a collection

called "The Rogue's Lexicon." And we use a lot of those words in the film.

And in some cases we could have done more, but it was almost--you would have

to have subtitles.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: And so what Tim Monich first discussed was listening to a

recording of Walt Whitman, the only recording of Walt Whitman I believe,

reciting four lines from one of his poems about New York. And one of the

phrases was the `ample streets of New York,' if I'm not mistaken. But I know

the word `ample' was in there. And we say ample (pronounced AM-pul); Whitman

said ample (pronounced EAM-pul) apparently on the wax disk cylinder, which

made a flat A. Then I remember Louis Auchincloss talking to me after "Age of

Innocence" and talking about the Mrs. Mingett character who's based on Mrs.

Jones, the original Mrs. Jones. And he said that they spoke in an odd way, he

said, at times. He said, for example, Mrs. Jones would have said to her

children, `Don't forget to take your pearls (pronounced POY-uls), girls

(pronounced GOY-uls).' So then you got pearls, girls, ample (pronounced

POY-uls, GOY-uls, EAM-pul) and suddenly becoming like New York cabbies in the

'30s, '40s and '50s, you know.

GROSS: Exactly, yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: The Bowery Boys, you know. And so we went with that. And he

started writing--I mean, he started reading--Daniel started reading the Bible

aloud and working with an accent that way with Tim. So we created our accent

based on what was written.

GROSS: We'll talk more with Martin Scorsese about "Gangs of New York" in the

second half of the show. Here's Daniel Day-Lewis as Bill the Butcher. I'm

Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "Gangs of New York")

Mr. DANIEL DAY-LEWIS: (As Bill the Butcher) You know how I stayed alive this

long, all these years? Fear, the spectacle of fearsome acts. Somebody steals

from me, I cut off his hands; he offends me, I cut off his thumb; he rises

against me, I cut off his head, stick it on a pike, raise it high up so all in

the streets can see. That's what preserves the order of things.

(Soundbite of music)

(Announcements)

GROSS: Coming up, the history behind "Gangs of New York." We talk with Tyler

Anbinder, author of "Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood

That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World's Most

Notorious Slum."

And we continue our interview with Martin Scorsese.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with Martin Scorsese. We're

talking about his new film "Gangs of New York," which is set in Five Points,

the notorious 19th century slum in Lower Manhattan. Last week, Scorsese won a

Golden Globe for directing the film.

It's not giving away anything about the story to say that at the end of the

film, the film kind of dissolves and we see a modern...

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes, all New York.

GROSS: ...New York skyline.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah.

GROSS: We see a couple of New York skylines as they evolve, and in the final

skyline, the World Trade Center is in it.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes.

GROSS: So that's the final image that we see. Did you think of adding a

post-September 11th, post-World Trade Center skyline?

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah, it's interesting. From way back in the very first draft,

Jay Cocks' draft in '78, '79, that was the way it ended. We knew that we were

diehard New Yorkers and it had to end with the skyline being built. It just

had to. In fact, we have a second part of the story that we wanted to do

which was building the Brooklyn Bridge and how the bridge linked Manhattan to

the rest of the country or vice versa. And so it had to end with that. We

just couldn't resist it.

The thing about it, of course, is that we did that painting and I should say

series of dissolves and paintings before September 11th. And right after it,

I thought about it and, you know, we're making a film. I felt that taking out

the towers was not the right way to go. I felt we should leave them in. The

people in the film, good, bad or indifferent, were part of the creation of

that skyline, not the destruction of it. And if the skyline collapses,

ultimately, we're aware of the struggle of humanity if there's any left

building up another one.

I think the sense of time going by, the sense of civilization changing and

primarily the idea of the city that we know now coming out of this

extraordinary struggle which not many people really know about. And so I felt

it was more--I felt it not would have been right to go in and keep revising

the New York skyline in moves, erasing the two towers. That was the way I

left it.

GROSS: You know, it's so interesting. "Gangs of New York" is about learning

about the past of Manhattan, your home. And then as you're making the movie,

September 11th happens and Manhattan gets transformed in a horrible and

shocking and totally unpredictable way. So your feelings about Manhattan must

just be so deep right now.

Mr. SCORSESE: It's just part of me and, you know, I think probably was even

stronger because I spent the first six years of my life in Queens. And when

we were catapulted back on to Elizabeth Street, the tenements where my mother

and father were born, not in hospitals but in the tenements, with all that

life in the street which at first was terrifying and then I sort of found my

way to survive in it was such a strong impression. There was so many cultures

thrown together, so many religions, so fascinating, just the cuisine alone,

the different cuisines, just being near the Chinese was fascinating. So this

is--the city for me is the center of the world that way. In the film, it

represents--New York City represents a city that, according to a lot of

historians, felt that in the 19th century if democracy didn't work in New

York, it wasn't going to work in the rest of the country.

GROSS: One last quick question. There's been, you know, news coverage of the

fact that your initial edit of "Gangs of New York" was much longer...

Mr. SCORSESE: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: ...and there was a tussle with Miramax on that.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yeah, I've got news for you.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: You know, every film I made, the first edit is longer.

GROSS: Right. That's right.

Mr. SCORSESE: Isn't that something? I don't know. I don't know. Listen,

are you going to edit this program...

GROSS: Yes.

Mr. SCORSESE: ...because if you edit it, you're ruining the original version

I want you to know.

GROSS: Right. No, no, I hear you.

Mr. SCORSESE: That's what it's come to.

GROSS: I hear you.

Mr. SCORSESE: There's no doubt Harvey and I fighting all the time. It's just

the nature of our personalities, and the nature of a big movie where they have

a certain amount of money and I wanted more.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: It just goes on and on and on like that.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SCORSESE: And then the nature of the cutting of the film. I kept a track

of every screening and how long the film was. Normally, Thelma Schoonmaker

and myself screened the picture eight, nine times and the rest...

GROSS: She's your editor. Yeah.

Mr. SCORSESE: Yes, Thelma Schoonmaker. And she's been editing everything

with me since former years, since "Raging Bull," 1980. And some films go a

little faster. Bigger films go a little longer. And we kept revising and

working on the picture, writing dialogue, things like that, all the way

through the editing process which I did in "Casino," too. Not in

"GoodFellas," in "Age of Innocence" somewhat and in "Casino" definitely.

"Kundun" was a very, very difficult edit that took almost a year to do. We

had to revise and restructure the picture from the original script, but in a

case like that, you can say, `Well, the original cut.' Well, yeah, but we

didn't think that was the movie, you see?

So here we have "Gangs of New York." Cut number one I believe was--I forget

the date, but it was three hours and 38 minutes. That was our assembly. That

was everything we knew and the kitchen sink thrown in, you know? But did it

work? No. So two days later, I recut it and it came down to three hours and

37 minutes. I cut out one minute. So now we begin a long, arduous process in

which I will have to take everybody's opinions because I want to see where

we're going, not only the studio's going to give opinions through Harvey and

other people with him, but the writers, our friends who come to see these

films. We have all that listed. There were 18 screenings ultimately of the

film. Eighteen screenings and there's not one version that I would say,

`That's my original version.' This is all a series of changes and rewrites

and restructuring at times till finally, finally--it's like a giant

sculpture--it's come down to the movie you see in the theater.

As far as putting new scenes on the DVD, yeah, there are some scenes I cut up,

but there's--How should I put it?--nothing I'm really fond of, that I like,

that I thought belonged in the picture ultimately and that's about it.

GROSS: Some people think they're eventually going to see your definitive

director's cut. That's not going to happen?

Mr. SCORSESE: I'm afraid not. I'm afraid not. Sorry to disappoint everybody

because I know that--you know, I do a lot with film restoration and film

preservation and, you know, there were directors' cuts of Sam Peckinpah's

"Wild Bunch" and "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid" and films like that. And

they finally were saved. Those are still around. There are directors' cuts

of, you know, the famous "Greed" by Erich von Stroheim and so many other films

and they're gone, destroyed. But in this case, on the DVD we'll have plenty

of featurettes and, wait, I might show some alternate takes, how the actors

were improvising. That might be interesting, but ultimately, I really feel

there was nothing special that I could--How could I put it?--really regret not

going in the picture and not staying in the film.

I mean--and you could think another way and that is we should have had another

30 pages of scenes and shot another 25 days or 30 days and made the film an

hour longer but we didn't have them.

GROSS: That's right.

Mr. SCORSESE: So, you know, it would have been like--What's it like?--the

old spectaculars where you had an intermission in the middle, you know? So

that I kind of would have liked, but in this way, there's certain things I

must say I found that were slow and ponderous and repetitious and I said,

`Let's move.'

GROSS: Martin Scorsese, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. SCORSESE: Thank you. Thank you.

GROSS: Martin Scorsese's new film is "Gangs of New York." He'll receive a

lifetime achievement award from the Directors Guild of America March 1st.

Coming up, we talk with historian Tyler Anbinder about his book "Five Points,"

about the 19th century slum in which "Gangs of New York" is set.

This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Tyler Anbinder discusses the New York City neighborhood

known as Five Points from his book "Five Points"

TERRY GROSS, host:

The film "Gangs of New York" is based on a 1928 book of the same name by

Herbert Asbury. It's been republished and is currently on the best-seller

list. Historian Tyler Anbinder says many of the most sensational stories in

the book are based on the unreliable press coverage of the time and aren't

true. Anbinder is the author of the book "Five Points: The 19th-Century New

York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became

the World's Most Notorious Slum." Anbinder is an associate professor of

history at George Washington University. He consulted with Martin Scorsese on

the screenplay of "Gangs of New York." Five Points was located about a

half-mile north of the Brooklyn Bridge. The area is now the lower part of

Chinatown just south of Canal Street at the foot of the Bowery. I asked Tyler

Anbinder what made Five Points notorious.

Professor TYLER ANBINDER (Author, "Five Points"): Living conditions for the

predominantly immigrants who lived in the neighborhood were as bad as anywhere

in the United States and perhaps anywhere in the Western world. The

neighborhood had been built over what had been a lake in the south central

part of Manhattan. They filled over the lake, but they didn't do a very good

job of it. And so the buildings they built over the lake began to sag and

droop almost immediately. As a result, the wind and the winter poured in, and

so it was very cold. And the immigrants who were coming to Five Points were

the poorest of the poor immigrants coming to the United States, people who

literally could afford to go not farther once the boat dropped them off in New

York. And so these tenements were terribly overcrowded. And once they became

overcrowded, the sanitary conditions in the tenements became really

horrendous. You had outhouses in the back yards that overflowed and people

who got terrible diseases like cholera as a result of those poor sanitary

conditions.

GROSS: In Martin Scorsese's film, "Gangs of New York," the conflict revolves

around the Irish immigrants and the group known as the Natives which are

American-born people of Protestant Anglo-Saxon descent who hate all the new

immigrants coming in, thinking the new immigrants are ruining New York and

ruining America. Was that real conflict that was going on in Five Points?

Prof. ANBINDER: Not so much in Five Points. You've got a neighborhood

that's, in terms of adult population, 80 or 90 percent immigrant. And so a

nativist gang is going to get pummeled in Five Points. And so the idea that's

portrayed in the movie that there's this nativist gang led by Daniel Day-Lewis

that controls Five Points could never have happened because simply the Irish

were too numerous in Five Points. So the nativists were going to be in other

parts of the city, were rarely going to show their faces in Five Points

because they knew they would not be welcomed there.

GROSS: So the butcher character played by Daniel Day-Lewis, there's no

historical person who that character's based on?

Prof. ANBINDER: Oh, no. The Bill the Butcher character is based on really

two people. The one he's named after was a real New York City politician

named Bill "The Butcher" Poole who had started as a butcher. He was not a

nativist gang leader. He was a Whig politician, a member of the Whig Party

uptown not down in Five Point and became famous really overnight because he

had gotten into a fight with an Irish-American politician. And that

politician's friends then came and shot Poole and Poole supposedly said as he

lay dying on this salon floor on Broadway, `Goodbye, boys, I die a true

American.' And the movie has Daniel Day-Lewis saying that when he's killed at

the end of the movie.

The other character that the Daniel Day-Lewis figure is based on is Isaiah

Rynders. And actually more of what's portrayed in the movie matches this

fellow Rynders. He was a gang leader more so than Bill Poole was. He had a

gang made up mostly of ex-prizefighters, bare knuckle prizefighters who he

would lead to the polls to intimidate people from voting for Rynder's

opponents. And that was very much a common thing in the 19th century. If you

wanted to win an election, you put muscle at the polls to stop people from

voting for your opponent. And Rynders actually did try to go to Five Points

and try to take over Five Points' politics and he brought his gang with him.

The Irish came. This was at a primary meeting and the Irish came and opposed

him. And they had a big brawl, and in the end, the Irish had won and Rynders

was kicked out of the neighborhood and that was the end of it.

So Scorsese has taken those two stories, the one of Poole and the one of

Rynders, that are both told in the Asbury book "Gangs of New York" and made

those into the character of Bill Cutting in the movie.

GROSS: Let's talk a little bit more about what life in Five Points must have

been like. You write about one building called the Old Brewery, which you

describe as `the most repulsive building of its day; a vast dark cave, a black

hole into which every urban nightmare and unspeakable fear could be

projected.'

Prof. ANBINDER: The Old Brewery was, as the name implies, once a brewery

sitting on the shores of the old Collect Pond, using the water from there to

make the beer. It was closed down and converted eventually into a tenement.

And it was particularly notorious, first, because it was a huge building, an

industrial building. And when they subdivided it, many of the apartments had

no windows at all. And so, of course, there aren't too many people who are

going to voluntarily live in an apartment with no windows and no light. So

only the poorest of the poor residents of Five Points lived there, the most

desperate people, the people with hardly any money.

And as a result, conditions there became quite terrible. The darkness,

disease was rampant there because of the lack of ventilation, the lack of

proper sanitary facilities, because you've got this huge building with

hundreds of inhabitants and not nearly the outhouse facilities to accommodate

them. It was a favorite hideout for thieves from the neighborhood who would

run in there, hide their loot from the police for a later time. So because of

the crime, because of the destitution, because of the overcrowding, the Old

Brewery became the most notorious tenement probably that New York ever had.

GROSS: In "Gangs of New York," fighting and brutality become sport and

entertainment. I mean, you see this in theaters as well as on the street.

What was entertainment like in Five Points?

Prof. ANBINDER: Fighting was definitely a form of entertainment in 19th

century New York. You had bare-knuckle prizefighting, not done in the city

itself because it's illegal, not done on a barge as is portrayed in the movie,

either, but you'd go to a rural place like Staten Island or some other place

where these fights would be held. But you did have sparring in bars as a

spectacle. People would come to these bars to see the sparring that went on.

There were all sorts of favorite modes of entertainment in Five Points, in

particular, dancing was a favorite. The neighborhood was famous for its dance

hall. These tended to be basement dance halls, tiny plays by modern

standards, you know, a room maybe 25 feet wide and at most 50 feet long. And

that had to include, of course, chairs and a bar as well, and a tiny dance

floor. And you'd have a fiddler in the corner maybe with someone playing a

tambourine as well or harmonica. And people would dance.

And, in fact, it appears that it was in these Five Point dance halls that tap

dancing was invented as the Irish came to the neighborhood bringing their

native dances such as the jig, those kind of high-stepping dances. They met

the neighborhood's African-American inhabitants whose dances included things

like the shuffle. And it's said that in these competitions, friendly

competitions that developed amongst the Five Pointers, that tap dancing is

invented.

GROSS: "Gangs of New York" climaxes with the Draft Riots of 1863. What set

off these riots?

Prof. ANBINDER: The Draft Riots were set off by a number of things. First,

New Yorkers had never really accepted the idea of going to war against the

South. The New York economy was very much tied to the Southern economy. Much

of the cotton that was produced in the South came through New York on its way

to the mills of New England or Europe. New Yorkers saw their economy very

much as linked to that of the South through its financing, through the

merchants who handled the cotton and so forth. So New Yorkers were not that

thrilled to have to go to war to fight the South in the first place.

That became even more so when Lincoln, in the middle of 1862, announced the

preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, that beginning in 1863, if the South

did not give up, that the slaves would be freed. And that turned the war from

a war to save the Union into a war to end slavery. And New Yorkers were

especially not interested in fighting a war to end slavery. Most New Yorkers

did not see slavery as such a terrible institution, and were not willing to

lay down their lives to end it.

Then finally, in mid-1863, the Lincoln administration decided that because

volunteering for the Army was declining that a draft was necessary. Both the

South and the North instituted a draft in the middle of the war. And so now

for the first time, Americans might have to fight against their will, might be

dragged into the contest even if they objected to it. Part of the draft law

said that if you could pay $300, a drafted person could be exempted from the

war. And Five Pointers and poor New Yorkers, in general, hated that aspect of

the draft law. They thought that that turned the war into a poor man's fight,

and allowed the well-to-do to stay out of harm's way. So all those factors

combined to cause this terrible outbreak of violence when the draft begins in

July of 1863.

GROSS: So who rioted, and what were their targets?

Prof. ANBINDER: The rioters were predominantly Irish-American New Yorkers who

saw themselves as the target of the draft law and those who would be unfairly

singled out to serve in the Army. Their targets were really everything that

they saw as representations of the Republican Party. So they attacked the

homes of famous Republicans. They attacked the newspaper offices of those

newspapers that supported the Lincoln administration, and especially those

that supported emancipation. And they attacked New York City's

African-American population, pretty much attacking blacks anywhere they found

them all over the city, lynching many, burning down the city's black orphan

asylum. And so blacks in particular and symbols of Republican power, in

general, were the targets of the mob's rage.

GROSS: Military troops were called in to put down the riot. When were they

called in?

Prof. ANBINDER: After about the second day of rioting when it became clear

that this was not just a typical New York riot, troops were called in. And

the Army decided to send soldiers who had just been fighting at Gettysburg

days before, send them north to New York to help put down the civil unrest

there. And it was only after four or five days that finally the city calmed

down again.

GROSS: So were there a lot of Irishmen from Five Points who were

participating in these Draft Riots, and was Five Points turn apart as the

result of the riots?

Prof. ANBINDER: Five Pointers were not particularly active in the draft

riots. We know from looking at the arrest records that not a large number of

Five Pointers took place in the most serious fighting. Most of the fighting

during the Draft Riots took place uptown, and it was mostly participated in by

people who lived uptown. So, no, Five Pointers weren't terribly involved in

the most outrageous acts of violence during the fighting.

On the other hand, Five Points itself, like almost every neighborhood of New

York, was very much torn apart by the rioting because you have in the

neighborhood during the riot many of the neighborhood's black residents are

attacked probably by Five Pointers or at least with the--certainly, there's

got to be some help of the whites in the neighborhood to point out which

buildings the blacks lived in, because what the rioters tended to do was find

out which buildings housed blacks and then attacked those buildings, try to

burn those buildings down. So there was terrible violence against Five

Point's African-American population during the rioting even though Five Points

isn't usually thought of as the place where the riots took place.

GROSS: My guest is historian Tyler Anbinder, author of the book "Five

Points." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest Tyler Anbinder is the author of the book "Five Points," a

history of the notorious 19th century slum in Lower Manhattan. It's the

setting of Martin Scorsese's new film "Gangs of New York."

During the mid-1800s when "Gangs of New York" is set, which groups were

represented in the immigrant population of Five Points?

Prof. ANBINDER: The neighborhood was overwhelmingly Irish. About two-thirds

of the neighborhood's inhabitants were Irish immigrants or their young

children. But the neighborhood had other immigrants, as well. It had a

significant number--probably about 15 percent of the population, were German

immigrants. There were also significant numbers, even at this point, of East

European Jewish immigrants, especially from Poland, living in Five Points.

But it was predominantly an Irish neighborhood and it was known overwhelmingly

as an Irish enclave.

GROSS: The Irish were despised by a lot of Americans when they came here

because they were seen as, you know, the poor immigrants who were coming in

with their own culture, bringing poverty and--What else? What were the other

reasons why the Irish became so despised as an early immigrant group to the

United States?

Prof. ANBINDER: Part of it definitely has to do with the poverty. Widespread

poverty was something simply virtually unknown in America before the 1830s.

And so after especially the potato famine in the mid-1840s and you have tens

and hundreds of thousands of completely destitute people arriving in America,

many native-born Americans resented the fact that now you have widespread

poverty, that crime increases as a result, that this overcrowding of tenements

takes place. And that very much worried Americans even who didn't live in

neighborhoods like Five Points, because diseases like cholera, that they could

easily spread throughout a whole city and, you know, during various outbreaks

in the early 19th century killed tens of thousands of people in cities like

New York and Philadelphia. Cholera could spread from a poor neighborhood like

Five Points to a well-to-do neighborhood. And so for all those reasons,

immigrants' presence was resented.

The other very important factor, the one that's hard to appreciate today, is

that Americans thought of the United States as a Protestant nation. They

thought Protestantism was what made America great. So seeing so many

Catholics coming to the United States really made them fear that the very

fabric of the nation was going to change, that the Protestant values that they

thought had made America so economically prosperous and so free, that these

things were all threatened by Catholics, especially because Catholics were

stereotyped in this time to be people who pretty much followed whatever they

were told by their priests and their bishops. And so they were thought that

they could very much change American politics by creating a voting bloc that

could be controlled by a single individual or a set of Catholic leaders.

GROSS: What would you say is the legacy of Five Points?

Prof. ANBINDER: One legacy of Five Points is that Five Points, in a way,

taught Americans now to deal with poverty. It was in Five Points that many of

the things we take for granted today--substance abuse, job training, child

care, things that we now accept as the most important facets of helping people

get out of poverty--these were things that were tried for the first time in

Five Points, because Five Points--poverty was so bad that the old things that

Americans had done to try to deal with it just didn't work. And so these new

things were tried, and many of them became standard parts of the social

service system that we know today.

Another legacy of Five Points is that--as the movie portrays very well--it was

in places like Five Points that Americans had to learn to accept a multiethnic

nation. In the early 19th century, the United States was overwhelmingly

Protestant, and in Five Points, Americans for the first time had to deal with

the fact that more people want to come to the United States than just

Protestants, just English people, for example. And it was in places like Five

Points that different ethnic groups, different religious groups for the first

time had to learn to get along. And it wasn't always very easy and often

there was a lot of violence, a lot of resentment. But eventually, it was

through places like Five Points and the multiethnic nation that we know today

was created.

GROSS: Tyler Anbinder, I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

Prof. ANBINDER: It's been my pleasure.

GROSS: Tyler Anbinder is the author of the book "Five Points." He's an

associate professor of history at George Washington University.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.