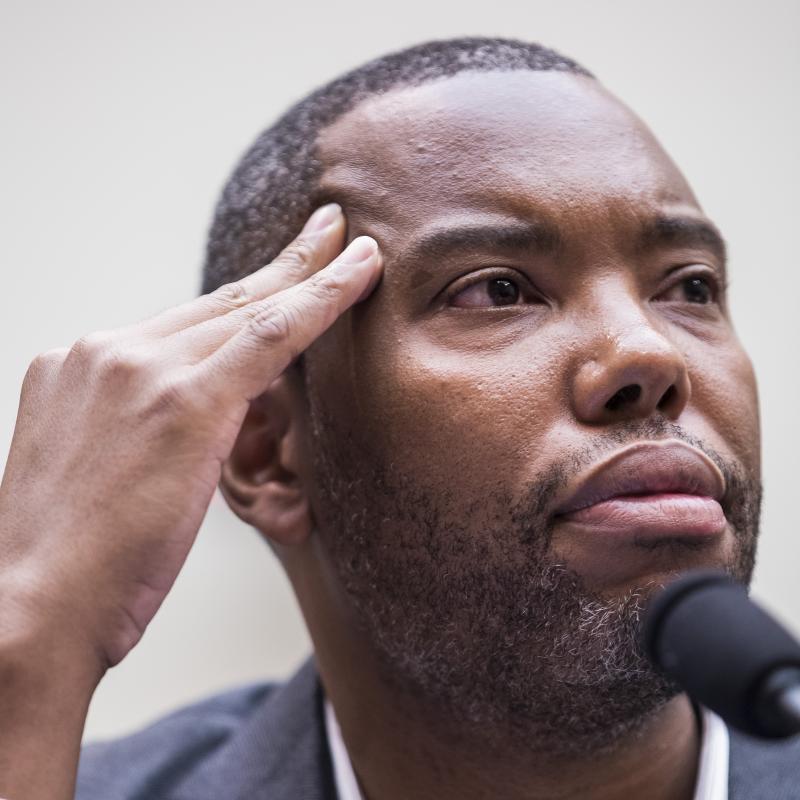

Journalist, Author Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates grew up in the post-civil rights era, son of a publisher and former Black Panther; he's a contributing editor and blogger for The Atlantic magazine and author of the memoir The Beautiful Struggle: A Father, 2 Sons, and An Unlikely Road to Manhood.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on January 19, 2009

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090119

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Congressman, Civil Rights Icon John Lewis

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross. On this Martin Luther King Day, the day before the inauguration of America's first African-American president, we hear from a leader of the civil rights movement who risked his life marching for the right of African-Americans to vote. From 1963 to '66, John Lewis chaired the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, mobilizing students to protest against segregation and for voting rights. He was a leader of the now-famous voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, which ended soon after it started when Alabama state troopers attacked the demonstrators on the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma in what became known as Bloody Sunday.

Lewis was a close associate of Martin Luther King. He was the youngest speaker at the 1963 march on Washington, which ended with King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Since 1987, Lewis has served in Congress representing Georgia's 5th District, which includes Atlanta. He recorded our conversation from his office. He told me he grew up in Alabama at a time when there was one county whose population was 80 percent African-American, but there wasn't a single registered black voter.

Congressman Lewis, welcome to Fresh Air, and thank you so much for joining us. When you were a young man, were you ever challenged at the polls? Did you have a hard time registering or did anyone ever try to prevent you from voting?

Rep. JOHN LEWIS (Democrat, Georgia): When I was growing up in rural Alabama, it was impossible for me to register to vote. I didn't become a registered voter until I moved to Tennessee, to Nashville as a student.

GROSS: Why was it impossible?

Rep. LEWIS: Black men and women were not allowed to register to vote. My own mother, my own father, my grandfather and my uncles and aunts could not register to vote because each time they attempted to register to vote, they were told they could not pass the literacy test. And many people were so intimidated, so afraid that they will lose their jobs, they will be evicted from the farms, and they just - they almost gave up.

GROSS: Your parents were sharecroppers. Now...

Rep. LEWIS: My mother and father and many of my relatives had been sharecroppers. They had been tenant farmers like so many people in the South. They knew the stories that had occurred. They knew places in Alabama where people were evicted from their farm, from the plantation. They read about, they heard about incidents in Tennessee where people were evicted from the farms and plantations back in 1956, in 1957 in West Tennessee between Nashville and Memphis, Tennessee.

GROSS: Now because of that did you - did your parents tell you not to bother to try to vote because it would be dangerous, they might lose their farm? I mean, you were - you were educated, you could certainly pass the literacy test.

Rep. LEWIS: My parents told me in the very beginning as a young child when I raised the question about segregation and racial discrimination, they told me not to get in the way, not to get in trouble, not to make any noise. But we had people that were educated. We had teachers, we had high school principals, we had people teaching in colleges and university in Tuskegee, Alabama. But they were told they failed the so-called literacy test.

GROSS: So did you go to the registration place and try to regist er or did you not even bother?

Rep. LEWIS: I didn't bother in Alabama. I didn't seek to get registered until I moved to Tennessee.

GROSS: One of the more dramatic moments of the civil rights movement was a march that you helped lead in 1965 of about 600 people. The march was supposed to be from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama demanding voting rights but the marchers were stopped soon after you started marching, and you were beaten by the police. Would you talk first a little about the goal of that march?

Rep. LEWIS: In 1965, the attempted march from Selma to Montgomery on March 7th was planned to dramatize to the state of Alabama and to the nation that people of color wanted to register to vote. In Selma, you could only attempt to register to vote on the first and third Mondays of each month. You had to go down to the courthouse and get a copy of the so-called literacy test and attempt to pass the test. And people stood in line day in and day out failing to get a copy of the test or failing to pass the test.

So after several hundred people had been arrested and people had been beaten and one young man had been shot and killed, we decided to march. And on Sunday afternoon, March 7, about 600 of us left a little church called Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, and started walking in an orderly, peaceful, nonviolent fashion through the streets of Selma. We were walking in twos, no one saying a word. We came to the edge of the bridge crossing the Alabama River, we continued to walk. We came to the highest point on the Edmund Pettis Bridge. Down below, we saw a sea of blue - Alabama state troopers. And we kept walking, and we came within hearing distance of the state troopers, and a man identified himself and said, I'm Major John Cloud of the Alabama state troopers. This is an unlawful march. You will not be allowed to continue. I give you three minutes to disperse and return to your church.

In less than a minute and a half, the major said, troopers advance. And you saw these men putting on their gas masks. They came toward us beating us with bull whips, night sticks, trivving(ph) us with horses and releasing the tear gas. I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a night stick. I thought I saw death. I thought I was going to die. I had a concussion there at the bridge, and almost 44 years later, I don't recall how I made it back across that bridge through the streets of Selma.

But I do recall being back at the church that Sunday afternoon. The church was full to capacity, more than 2,000 people on the outside, and someone said to me, John, say something to the audience. Speak to them. And I stood up and said something like, I don't understand it - how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam but cannot send troops to Selma, Alabama to protect people who only desires to register to vote.

GROSS: What was the impact, do you think, of that march on the actual passage of the Voting Rights Act?

Rep. LEWIS: The march created a sense of righteous indignation among the American people. When they saw the photographs, when they read the stories, when they heard the news on the radio, watched it on television, they didn't like it. A few days after Bloody Sunday, there wasdemonstration in more than 80 American cities. At the White House, at the Department of Justice people were demanding that the government act.

President Johnson didn't like what he saw. He called Governor Wallace, the governor of Alabama at the time, to come to Washington and tried to get assurance from the governor that he would be able to protect us if we decided to march again. The governor could not assure the president, so President Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard, called up part of the United States military, and eight days after Bloody Sunday, President Lyndon Johnson spoke to a joint session of the Congress and made one of the most meaningful speeches any American president had made in modern time on the whole question of voting rights, and he introduced the Voting Rights Act.

And I was sitting in a home in Selma, Alabama that evening when President Johnson spoke to the nation and spoke to the Congress, sitting with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. And at one point in the speech, before Dr. - before President Johnson, rather, concluded the speech, he said, and we shall overcome - and we shall overcome.

I looked at Dr. King, tears came down his face, and we all cried a little to hear President Johnson say, and we shall overcome. And he said to me and to others in the room, we will make it from Selma to Montgomery, and the Voting Rights Act will be passed.

Finally, two weeks after Bloody Sunday, we started on the third effort to make it from Selma to Montgomery. And 300 of us marched all of the way, but by the time we walked into Montgomery there were more than 25,000 citizens. And that effort led the Congress to debate the Voting Rights Acts and pass that act, and President Johnson signed it into law in August of 1965.

GROSS: Can you talk a little bit about how your mindset changed to go from what your parents told you, which was don't make trouble, it's too risky, to making a lot of trouble, to leading marches, to be willing to get beaten on the head and knocked unconscious to stand up for what you felt was right?

Rep. LEWIS: When growing up, I saw segregation. I saw racial discrimination. I saw those signs that said white men, colored men. White women, colored women. White waiting. And I didn't like it. I would ask my mother and ask my parents over and over again, why? They said, that's the way it is. Don't get in the way, don't get in trouble. I was so inspired by Rosa Parks in 1955. I was 15 years old. I was inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr. I heard his words on all radio. It seemed like he was saying to me, John Lewis, you too can make a contribution.

GROSS: What was he saying on the radio?

Rep. LEWIS: He was saying...

GROSS: Was this a sermon or something or a speech?

Rep. LEWIS: It was a speech but also a sermon. He was speaking at a church in Montgomery. And he was saying, in effect, that we must not just be concerned about the Pearly Gates and the streets with milk and honey. We have to be concerned about the streets of Montgomery and the doors of Woolworth. That we have to be concerned about jobs, about blacks working as cashiers, of people being able to try on clothing and bring down those signs. And I said to myself, if I ever got a chance to strike a blow against segregation and racial discrimination, I'm going to play my part or do my part.

I was so inspired by Dr. King that in 1956, with some of my brothers and sisters and first cousins - I was only 16 years old - we went down to the public library trying to check out some books, and we were told by the librarian that the library was for whites only and not for colors. It was a public library. I never went back to that public library until July 5th, 1998 - by this time I'm in the Congress - for a book signing of my book, "Walking with the Wind."

GROSS: Your memoir.

Rep. LEWIS: And they gave me a library card after the program was over. And I was inspired. I studied the philosophy and the discipline of non-violence in Nashville as a student, and I staged a sitting-in in the fall of 1959 and got arrested the first time in February 1960.

GROSS: Now, you describe the difficulty your parents had accepting the risks that you were taking as a civil rights activist. As an activist, did you find it was difficult to convince the older generation to join up with the movement? Was it easier to convince younger people than older people?

Rep. LEWIS: It was much easier to convince younger people, to convince students, whether they were high school or college students. In the South during that period, there was so much fear. There were people that were afraid to be a friend(ph). But there were others who said, we'll hold the mass meetings, the rallies, the voter registration workshop in a church. It was this feeling, well, it's taking place in a church. It must be OK. It must be all right.

There was ministers, religious leaders that was afraid to say anything from their pulpits because they thought, for good reason, the church could be burned down, could be bombed. So we had to do a lot of convincing. And we would go into the fields where people were working in the fields and try to convince some of the field workers. We would go into beauty shops, the barber shops, knock on the doors of people's homes trying to get them to become participant, to get involved, to come to a rally, come to a mass meeting.

GROSS: Give me a sense of what you'd say.

Rep. LEWIS: We would said to people, you know, you've been living here for 40 years, for 50 years. Your street is not paved. You have a dirt road. You don't have clean water. If you want to change that, you must register and you must vote. You can get someone else elected. Come to a mass meeting, come next Monday. The neighbors are coming. Your uncle is coming. Your children are coming. You should be there. I tell people, we're going to have a march for the right to vote. Don't be afraid. You may get arrested, but a lot of other people will be getting arrested with you. And some people would be convinced, and some would not.

GROSS: My guest is Congressman John Lewis of Georgia. We'll talk more about his years as a civil rights activist, his memories of Martin Luther King and his thoughts about Obama's inauguration after a break. This is Fresh Air.

(Soundbite of music)

If you're just joining us, my guest is Congressman John Lewis of George, and we're talking about his years as a civil rights activist.

On this Martin Luther King Day, I'd love to hear the story of how you first met Reverend King.

Rep. LEWIS: In 1957, when I finished high school, I was 17 years old. This was two years after the Montgomery bus walkout, two years after Rosa Parks had taken a seat, and Dr. King had emerged as a national leader.

I wanted to attend a little college about 10 miles from my home, an all-white state college. I submitted my high school application. I never heard a word from the college, so I wrote a letter to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I didn't tell my mother or my father. Dr. King wrote me back, sent me a round-trip Greyhound bus ticket and invited me to come to Montgomery to see him.

In the meantime, I had been accepted at a little college in Nashville, Tennessee, so in September 1957 I went off to school to Nashville. And after being there for two weeks, I told one of my teachers that I had been in contact with Dr. King. This teacher informed Dr. King that I was in school in Nashville, so Martin Luther King, Jr. got back in touch with me and suggested when I was home for spring break to come and see him. So my father drove me to the Greyhound bus station. I boarded the bus to travel from Troy to Montgomery.

And a young lawyer by the name of Fred Gray, who was the lawyer for Rosa Parks, for Dr. King and the Montgomery movement, met me at the Greyhound bus station and drove me to the First Baptist Church and ushered me into the office of the church. I saw Martin Luther King, Jr. standing behind the desk. I was so scared I didn't know what to say or what to do. And Dr. King spoke up and said, are you the boy from Troy? Are you John Lewis? And I said, Dr. King, I am John Robert Lewis - I gave him my whole name. And that was my meeting of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., for the first time.

GROSS: So what did he do? Did he try to encourage you to keep trying to get into that white college, or did he say, forget college, just come join the movement, work with me?

Rep. LEWIS: No. Martin Luther King, Jr. said to me, we want to help. If you want to go to Troy State, we will help you. We would hire Fred Gray as the lawyer to file a suit against Troy State. But he went on to say, if you really pursue this effort, your family home can be bombed or burned down. They could lose their jobs. You may be beaten. Things can happen to you but you must be willing to do it. And I told him I was willing to do it. But he said, you must go home and talk to your mother and talk to your father and get them to be willing to file the suit.

So that afternoon, I went back to Troy, Alabama, met with my mother, met with my father, told them about the discussion I had with Dr. King. And they were so scared, they were so frightened, they didn't want to have anything to do with me pursuing my effort to enter for a state college. So I continued to study in Nashville.

GROSS: And did other things in the civil rights movement instead.

Rep. LEWIS: Well, I continued the sit-ins, got on the Freedom Rides and became an active participant not just in Nashville but throughout the American South.

GROSS: What impact did his assassination have on you?

Rep. LEWIS: The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. made me very, very sad, and I mourned and I cried like many of our citizens did. As a matter of fact, when I heard that he was - that he had been assassinated, I was with Robert Kennedy in Annapolis, campaigning with him. But somehow I said to myself, I'm not going to become bitter or hostile. I'm not going to give up or give in. I threw myself more into the campaign, and I made a commitment to myself that I would do what I can to continue the work of Dr. King, and later, after Bobbie Kennedy was assassinated two months later, to continue his effort to make our country a more just, a more fair country.

GROSS: Congressman John Lewis of Georgia will be back in the second half of the show. He was a leader of the civil rights movement and a close associate of Martin Luther King. I'm Terry Gross, and this is Fresh Air.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross, back with Congressman John Lewis of Georgia. In the '60s, he was a leader of the civil rights movement and a close associate of Martin Luther King. He risked his life leading a voting rights march that was planned to go from Selma to Montgomery but it ended quickly when the demonstrators were attacked by Alabama state troopers. Just a few months after that march and partly as a result of it, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, outlawing discriminatory practices. It was signed by President Johnson in August 1965.

Do you think that there have been incidences where the African-American vote has been suppressed in recent years in spite of the Voting Rights Act?

Rep. LEWIS: There have been efforts in recent years and as recently as this past election with it being a deliberate and systematic attempt to suppress the African-American vote. We had a case in some parts of Virginia where people tried to say to African-Americans - to would-be Democratic voters, you're not supposed to vote on Tuesday, November 4th. You're supposed to vote on Wednesday, November 5th. They were saying, in effect, that there's going to be such a big turnout, such a massive turnout, and you don't want to stand in these long line.

This is not necessarily a state, a political party doing it, but it's individuals. And there have been cases where people go to the polls planning to vote, waiting in line, and you see people standing, taking names, taking the license plates on cars of how law enforcement people are standing nearby and telling people that if you go and attempt to vote, you cannot vote becase you owe a bill - you haven't paid your taxes. And people are intimidated. They're harassed.

GROSS: I want to quote something that you wrote in an op-ed piece in October of 2003. And this was about gay rights and the right for gay people to marry. You wrote: I have fought too hard and too long against discrimination based on race and color not to stand up against discrimination based on sexual orientation. I've heard the reasons for opposing civil marriage for same-sex couples. Cut through the distractions, and they stink of the same fear, hatred and intolerance I have known in racism and in bigotry.

Now, I've heard some African-American leaders say that it's wrong to make - I'm not quoting you here, I'm saying this part myself. Your quote has ended. And I'm saying, I've heard some African-American leaders say that it's wrong to make any connection between the civil rights movement and the gay rights movement because discrimination against African-Americans and discrimination against gays are completely - completely different things, and being gay and being black are completely different things. What's your take on that?

Rep. LEWIS: Well, I do not buy that argument. I do not buy that argument. And today, I think more than ever before, we have to speak up and speak out to end discrimination based on sexual orientation. Dr. King used to say when people talked about blacks and whites falling in love and getting married - you know, at one time, in the state of Virginia, in my native state of Alabama, in Georgia and other parts of the South blacks and whites could not fall in love and get married. And Dr. King took a simple argument and said, races don't fall in love and get married. Individuals fall in love and get married.

It's not the business of the federal government. It's not the business of the state government to tell two individuals that they cannot fall in love and get married. And so I go back to what I said and wrote those lines a few years ago, that I fought too long and too hard against discrimination based on race and color not to stand up and fight and speak out against discrimination based on sexual orientation.

And you hear people defending marriage. Gay marriage is not a threat to heterosexual marriage. It is time for us to put that argument behind us. You cannot separate the issue of civil rights. It one of those absolute, immutable principle - we got to have not just civil rights for some but civil rights for all of us.

GROSS: When you say not just civil rights for some, you even mean not just civil rights for African-American but for gay people too?

Rep. LEWIS: Not just civil rights for African-American, other minorities, but civil rights also for gay people.

GROSS: Are you concerned that now that Barack Obama is about to become president that a lot of people might be thinking, whew, wow, solved the racism problem, glad that's over, don't have to worry about that anymore. Don't have to take that into account anymore.

Rep. LEWIS: I am concerned that there are some feelings in some quarters in some corners that - what do people of color want now? We elected Barack Obama as president. It's over. People talk about the post-racial America. I see his election not as the end but as a continuum. But we're not there yet. We have not yet created the beloved community that Dr. King spoke of. I see this as a down payment - a major down payment on the dream of Martin Luther King, Jr. Even with this election, we still have a great distance to go before we lay down the bird in the race.

GROSS: Of all the people who have passed on who you were close to, who are some of the people who you were - who you most wish were here today to witness the inauguration of America's first African-American president?

Rep. LEWIS: Oh, I wish - I truly wish that so many people, many of these just indigenous people that stood in those unmovable lines in the heart of the Deep South. Many of the people that were on that bridge on Bloody Sunday, I wish they could be here today, but many of them are gone on. Individual like Fannie Lou Hamer, sharecropper in the Delta, Mississippi who was beaten but who testified at the Democratic Convention in 1964.

I wish that Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., President Johnson, President Kennedy and others could witness what is happening in America. There's countless individuals that I wish could be on the Mall, on the steps of the Capitol and see what is happening in America.

GROSS: And where will you be on Inauguration Day?

Rep. LEWIS: On Inauguration Day I will be on the platform sitting on the steps behind President Barack Obama. I don't know how I'm going to take it all in because from sitting on the steps, I will be able to look right down the Mall and see past the Washington Monument and see the Lincoln Memorial where we stood more than 45 years ago. And during those days, during that period, many of the people who voted for him could not register and vote.

GROSS: Congressman John Lewis, thank you so much for talking with us.

Rep. LEWIS: Well, thank you very much. Thank you.

GROSS: John Lewis spoke to us from his office on Capitol Hill. He's been a Democratic Congressman from Georgia since 1987. Coming up, coming of age in the post-civil rights era. We talk with journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates. This is Fresh Air.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

99560979

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090119

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Journalist, Author Ta-Nehisi Coates

TERRY GROSS, host:

My guest, journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, came of age in the '80s in a post-civil rights era where the gains of Dr. King and our previous guest, John Lewis, were a reality. In Coates' memoir, "The Beautiful Struggle," he writes that he felt all the great wars had been fought and he was left to rummage through myths of his fathers.

Coates grew up in an Afro-centric home in West Baltimore with parents who revered black leaders like Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X. His father, Paul Coates, was a Vietnam vet and former Black Panther who ran a small publishing company out of their basement called Black Classic Press.

Ta-Nehisi immersed himself in his father's books, as well as X-men comics, "Dungeons and Dragons," and hip-hop. He's now a contributing editor and blogger for the Atlantic magazine. His article about Michelle Obama, called "American Girl," is in the current edition. Ta-Nehisi Coates, welcome to Fresh Air.

Mr. TA-NEHISI COATES (Contributing Editor and Blogger, Atlantic Magazine; Author, "The Beautiful Struggle: A Father, Two Sons and An Unlikely Road to Manhood"): Thank you for having me, Terry.

GROSS: Now, you were born in 1975, and you grew up in the post-civil rights era, the son of a former Black Panther. What did Martin Luther King mean to you growing up?

Mr. COATES: Well, I had a very complicated relationship with Martin Luther King. I came up among people for whom I - quite frankly, black nationalism was a much larger influence. I hesitate to call my household a black nationalist household. My dad was a very sort of critical, unpredictable sort of person. But having said that, black nationalism and Malcom X had a huge influence on my upbringing, and I think between that and between how Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement was presented to us in school - which was basically every February us seeing tapes of people being beaten and shot and water-hosed - I don't know that I had the highest opinion of Martin Luther King as a young person because to us it looked like a kind of qualification of suffering. And I was much more - being a kid of that age, you know, interested in messages of pride and that sort of thing.

As I became an older person - and I'm talking about into going to college in my later teens and my early twenties and I began reading about him - I had a much different understanding of Martin Luther King and a much greater appreciation mostly for the fact of how, you know, he was basically an intellectual prodigy, and just as a young man, you know, going through college, that was very appealing to me. And how much he achieved at a relatively young age. I mean, I'm 33 right now, and Martin Luther King was, you know, basically had lived a good portion of his life.

And then later how he evolved post-Selma, you know, taking on the Vietnam War at a point when it probably was not the best move necessarily politically, and he just sort of cast that aside and did it anyway. That was and still is very inspirational to me.

GROSS: Let me read something that you wrote in the Washington Post in an op-ed. You wrote: King believed that the lion share of the population of this country would not support the rights of thugs to pummel people who just wanted to cross a bridge.

And this is a protest that you were referring to.

King believed in white people, and when I was a younger, more callow man, that belief made me suck my teeth. I saw it as weakness and cowardice, a lack of faith in his own people, but it was the opposite.

What did you mean there?

Mr. COATES: There's a natural inclination, you know, knowing the history of African-Americans in this country. And I think this is true for any group of people who have gone through some sort of struggle, who are at one point or at any point have been an oppressed minority to - how shall I say - glorify striking back, glorify, you know, in being a sort of me-first attitude. But I think what King taught me - and this is, you know, a lesson that, again, that sticks with me and I think it came through again in this election - is what there is to be guarded in believing in the humanity of other people.

I - you know, I always say in my work that I'm always interested in African-American humanity and bringing that out as much as I possibly can. But King believed in white humanity and the humanity of people who we don't necessarily see on a daily basis. And if you think about it, given how we live America - in terms of black and white is still fairly segregated. We don't necessarily interact with each other too often.

I always felt like it was an incredible leap of faith - as crazy as this sounds to say - even though I've never met this guy, he still goes home to his family the same way I do. He doesn't, you know, like cutting on his TV and seeing kids getting water-hosed. He doesn't like seeing women being beaten - as I said, for simply wanting to cross a bridge. He may have his own, you know, racial hang-ups, he may not want his daughter marrying a black man. But he can sympathize with the mere thing of wanting to cross a bridge. It's a simple, simple human act.

GROSS: And the bridge that you're referring to there is the Edmund Pettis Bridge...

Mr. COATES: Yes.

GROSS: The bridge that John Lewis tried to lead protesters across.

Mr. COATES: Right.

GROSS: But they were trampled by Alabama state police. How does your feelings about Martin Luther King - about the fact that he believed in the humanity of white people, he believed that white people wouldn't support the thugs who were beating civil rights demonstrators - how does that connect to how you see Obama?

Mr. COATES: I'll put it to you like this. Had you told me a year before election season started that there would be a black man who would go to Iowa and win the primaries, who would go to places like the Dakotas, who would go to Washington, places where there aren't significant populations of African-Americans and be successful there, I would not have believed you.

Had you went further and told me there would be a black man running in the Democratic Party in the general election who would go to Georgia and be competitive, who would go to North Carolina and win, go to Virginia and win, go out to New Mexico, Colorado, Indiana, be successful in Ohio, that a black man would do that on a Democratic ticket knowing what had happened with Democrats in the past, I wouldn't have believed you.

And a huge part of that was because of my broad impressions of white people. I'll just be straight and honest as I possibly can. You tend to paint with a broad brush, almost as a survival tactic, people who you've never seen. And you write whole communities off as hostile to you. Now, I understand that that's not the same thing as somebody writing off a whole community as inferior to you. It's a defense technique almost. But at the same time, it can cause you to close off worlds that could be accessible to you.

And I think Barack Obama - the most inspirational thing about all this is that he was able to see that. And not only that, he was able to see the humanity in other communities, and quite honestly, see how it would benefit him, how it was a limitation to him to not see the humanity, to not see that certain people, once they heard him talk, would be able to evaluate him as a human being.

I understand that there are all sorts of factors - an economy, a war, apresidency that was unpopular that helped him, but you know, I'm a strong believer that the field is what the field is. You know, you play on it, and that was an object lesson for me. It really, really was.

GROSS: Let me quote you again. You wrote: The favored rallying cry of black people is that we're not a monolith. How fascinating that some of us could only belatedly extend the same courtesy to white Americans.

Mr. COATES: Right.

GROSS: So it sound like Obama's election gave you faith in white people and taught you that white people aren't monolithic.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COATES: I hate to sound embarrassing, but yes. I guess that is - I mean, what - I can't run away from that. That is sort of true. Again, I want to stress, it's kind of a defense mechanism that you take out into the world as a black person. You want to shield yourself against things you've been talking about. The thing you have to understand is we come up from a generation of people who actually dealt with real serious, direct racism. I mean, you know - and so our parents taught us a certain way to be in the world in order to be successful and in order to - honestly, to prevent a level of emotional trauma that they might have incurred that we might incur from dealing on a personal basis with racism. I'm talking about people calling you the N word, people looking at you a certain way.

Part of that is you don't go certain places. So, you've - you know, may read that North Dakota is a very beautiful state, but you think there are no black people so I'm never going there. I got no reason to go to North Dakota. They don't want me there. And you don't know anything about North Dakota but that's how it shows up for you in your mind.

I was out in Colorado for the Democratic Convention and also for some business this summer. Beautiful, beautiful state. There were times when I didn't see a black person for a whole day. And you know, under normal circumstances - and I have to admit - when I, you know, when I was at first out there, it does give you a sort of, you know, OK, anything can happen out here sort of feeling. But I think, again, the confidence that Barack Obama showed, whether he was walking into a barbershop and, you know, he approached people as human beings, or whether he was in the middle of Colorado and there were no black people around, was deeply, deeply inspirational to me.

And I connect that to Martin Luther King's ability, again, to not just believe in people who did not live next door to him but to believe in people who historically had endorsed a system that had kept people like him down. And he just had a broad belief that at the end of the day, most folks, when faced with this, would do the right thing. And that's just - I mean, he paid for it with his life, no question, and you know, we're all fearful of what can happen to Barack Obama, but that was a great lesson in courage for me and in faith.

GROSS: My guest is Ta-Nehisi Coates. He writes and blogs for the Atlantic magazine. He has a piece in the current edition about Michelle Obama called "American Girl." More after a break. This is Fresh Air.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates. He writes and blogs for the Atlantic magazine. His memoir, "The Beautiful Struggle," just came out in paperback.

You write that you grew up obsessed with having been born in the wrong year, that all the great wars had been fought and you were left to rummage through the myths of your fathers.

Mr. COATES: That's right.

GROSS: What were some of the great wars that you thought were fought and over?

Mr. COATES: Well, you know, it was only later that I realized that this is something happens with most generations. So I mean, probably my son will look back on, you know, the whole thing with Barack Obama and say, man, I wish I had been around for that.

For African-Americans, and I think particularly for African-Americans of the slice of society that I was - young folks who came up in the late '80s, early '90s, were raised on hip-hop and conscious, quote unquote "black nationalist hip-hop," who went to historically black schools - our sense was that the great wars were the civil rights movement, were the black power struggles, were - had happened with Fred Hampton and with Malcolm X and with, you know, Martin Luther King indeed. That we would never to do anything that noble. I don't want to get too much off topic here, but my Dad had fought in the Vietnam War, had come back and joined the Black Panther Party and left the Black Panther Party, got into publishing books about African-American history and that sort of thing.

He was a man who I felt had been on the frontlines at a point in American history where things just totally changed. And whatever would happen to me, I had the feeling that I would never experience anything like that. I thought I would never live to see any sort of seismic shifts. The feeling was, again, we had moved into a new era.

GROSS: You write that many African-Americans learn to be bilingual, to be one way with black people and another way with white people. But you say, increasingly, as we move into the mainstream, black folks are taking a third road - being ourselves. Can you expand on what you mean by that?

Mr. COATES: Yeah. I think that the culture has changed in such a way that African-American culture has been blended into pop-culture in a manner that it's obvious to everyone. And not necessarily - that wasn't necessarily the case 20, 30 years ago. I don't even think it was the case 10 years ago. So when Barack Obama's on stage after that debate with Hillary Clinton and he dusts off his shoulder, everyone understands that because Jay Z is the sort of star at that point that he has more white fans than he has black fans. Everybody gets that. It's not a black thing as it would have been, I think, say, 20, 30 years ago.

When Barack and Michelle Obama give each other dap or give each other a pat - as we like to say amongst ourselves - it's not Barack and Michelle Obama who are racialized for doing that or who are scandalized for doing that, it's the people who have apparently been living in a time warp somewhere and call it a terrorist fist-stab. They're the ones who are seen as completely out of the loop because everybody knows what that gesture is. It's so mainstream now.

I think that moment and being where we are in history freed Barack Obama up, and I think it freed Michelle Obama up to talk to the country in a broad sort of way. And so they didn't have to particularly tailor messages. They could speak as they, quite frankly, would speak to African-Americans in the neighborhood. But it wouldn't be alien. Through the technology, we're all connected now. We're all - a lot of us are listening to the same music, seeing the same things, receiving the same symbols. And so I think that made things a lot easier.

GROSS: Your father for years has had a small publishing company. He used to publish in the basement when you were growing up. And among other things, he's published a lot of Afro-centric books. What does it mean to you to have a president whose father was from Africa?

Mr. COATES: You know, I've never thought about it like that. That's a very interesting statement. I have never really thought much about that. What meant more to me was to have a president whose father abandoned him because, again, as a black man, I knew so many kids who were in that situation.

There was a lot of criticism around Barack Obama's fatherhood speech, which I liked and I thought was given an extra level of credibility because he knew what that was. And that, obviously, is going to be one of the big issues that we're dealing with over the next four years or so. I thought that was really, really, especially significant and really gave him a level of insight to one of our big societal problems.

GROSS: Your father is a former Black Panther, was somebody who really stood in opposition to the government. Your son - who's how old now?

Mr. COATES: He's eight.

GROSS: He's going to become cognizant of politics in an era when there's an African-American living in the White House.

Mr. COATES: That's right.

GROSS: So, his idea of what the American government is is going to be, I think, pretty radically different than what your father's was. What do you think it might mean to your son growing up with Barack Obama as president?

Mr. COATES: Well, I think - to just put this in context - my dad was in the Black Panther Party when he was in his 20s. I don't think his idea with the government was - in his 20s - is what it is when he's in his 60s now. It's also probably true the government isn't what it was then.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. COATES: Having said all of that, that's a tough question to answer because it won't even be where I was - and this is something I think about all the time - I don't - we have a difficult time in our household even talking about race with him because you don't want to freight things. You don't want to put things on him that he doesn't actually even really have to deal with, that won't even be real for him.

I think, you know, that there's a lot of talk about what would be the effect of having a black president. And I think on people his age and actually younger, who won't enter into the world with the idea that a black president is somehow insane, I think that's the biggest effect. I think it will be a seismic shift. I did not expect to see a black president in my lifetime.

One of the differences between, I think, a lot of African-Americans who came over to Barack and, you know, some of the women who were supportive of Hillary Clinton, is there was almost an expectation of some women that there could be a woman president. It was almost like they didn't doubt it, that it could actually happen in their lifetime.

For black folks, this came out of left field, I think. We were really, really surprised. I mean, you have to remember, Barack Obama couldn't even get into the Democratic Convention in 2000. So it completely blind-sided us. I just - I didn't expect that. And so I think for him, it'll just be - it'll be completely different. It's very difficult for me to imagine, actually, in fact.

GROSS: Ta-Nehisi Coates, thanks so much for talking with us.

Mr. COATES: Thank you for having me, Terry.

GROSS: Ta-Nehisi Coates is a contributing editor and blogger for the Atlantic magazine. He has an essay in the current edition about Michelle Obama called "American Girl." His memoir, "The Beautiful Struggle," just came out in paperback. You can download pod casts of our show on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

99560982

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.