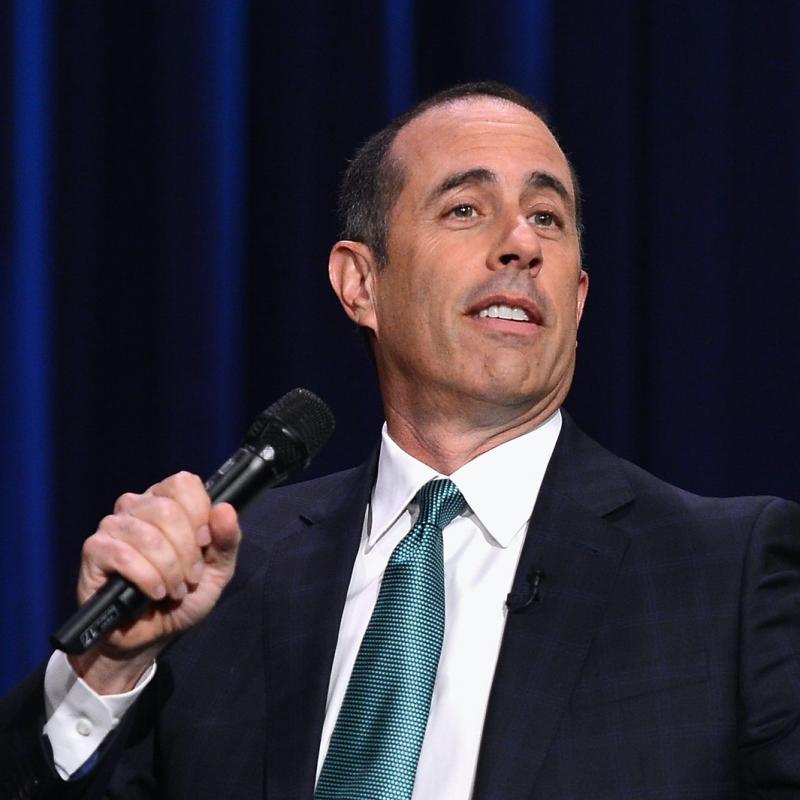

A-List Comedian Appears in a 'Bee' Movie

Comic and actor Jerry Seinfeld's latest project is the animated film Bee Movie, which he wrote and starred in. Seinfeld is best known for his work on the self-titled NBC series, which ran for nine seasons, earning the actor a Golden Globe Award and an Emmy Award.

Other segments from the episode on April 25, 2008

Transcript

DATE April 25, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Actor Casey Affleck on his two latest films, "Gone

Baby Gone" and "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward

Robert Ford"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, senior writer for the Philadelphia Daily

News, filling in for Terry Gross.

Casey Affleck has appeared in 22 films over the last dozen years, but he's

often been referred to as "the other Affleck," a reference to his older

brother Ben Affleck. But that's changing now, thanks in part to Casey

Affleck's starring roles in two films now out on DVD: "The Assassination of

Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford" and "Gone Baby Gone." Both performances

have won critical praise. "Gone Baby Gone" is the directorial debut of Ben

Affleck. Among Casey Affleck's other films are "To Die For," "Good Will

Hunting," "Gerry" and "Oceans 11," "12" and "13."

"Gone Baby Gone" is based on a novel by Dennis Lehane, who also wrote "Mystic

River." Affleck plays a small time private detective who's asked to help find

an abducted child. In this scene, he's visiting a drug dealer and is willing

to help the dealer out with a problem in return for help finding the missing

child named Amanda McCready.

(Soundbite of "Gone Baby Gone")

Mr. CASEY AFFLECK: (As Patrick Kenzie) We found what you were looking for in

Chelsea.

(Soundbite of pool balls clacking)

Mr. EDI GATHEGI: (As Cheese) What do I care about Chelsea?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: (As Kenzie) Because one of the idiots that robbed you lived

there.

Mr. GATHEGI: (As Cheese) What idiot?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: (As Kenzie) The one that you and Chris beat with a pipe and

shot in the chest.

Mr. GATHEGI: (As Cheese) I don't know about nobody getting killed. But if

somebody robbed me and end up dead, well, you know, life is a...(censored by

network).

Unidentified Actor #2: (In character) Cheese, we got your money. It was

buried in Ray's backyard. We want to give it back to you in exchange for

Amanda McCready. The two police outside are the only other people who know.

Mr. C. AFFLECK: (As Kenzie) No one gives a...(word censored by

network)...about what you did. I mean, I didn't even like Ray that much.

You're going to get your money, m mother gets her daughter back, and we'll say

we found the kid in the bushes or whatever. It's either this, real quiet, or

it's a thousand...(word censored by network)...cops kicking your door in,

putting their fat knees in your neck.

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: I spoke to Casey Affleck last fall, when "Gone Baby Gone" was

released in theaters. The film is set in Boston, where Casey and Ben Affleck

grew up.

Well, Casey Affleck, welcome to FRESH AIR. When you had to craft this

character, this private eye from this working-class neighborhood of

Dorchester, were there people that you knew that you grew up with that you

sort of drew on to craft this character?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, in different ways, yes. No, there is not one single

person, but I knew the accent, I knew the way that people dressed, and kind of

what music they listened to, what kind of jobs they had, what their attitudes

were towards everything from police to themselves to their children, I knew

what kind of slang that they used, you know. It's just, as an actor, it just

means that you don't have to go spend, you know, four months listening to a

dialect coach and trying to get the accent right and sort of wandering, you

know, getting to know people there just to figure out, like, when they wear

their sweats and when they put on their, like, ironed, you know, jeans.

DAVIES: Boston is a character in, you know, Dennis Lehane's novels, and it's

clearly a character in this film, and I think really evocatively drawn out by,

you know, by your brother as the director. Were there moments in the dialogue

in scenes that you kind of felt like, `This is really what I know. This is so

familiar to me'?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, I mean, just about all of it, except for the police

work. You know, any time we were shooting kind of down in the neighborhood

where the character lived and with people--you know, there's a scene in a bar,

and we go in there to talk to--we're looking for this missing girl, and this

is a place where the mother hung out. And so we go in there to talk to people

and find out, you know, see if we can get some information. And it's the

middle of the day, and there's about six or seven guys, you know, alcoholics,

you know, kind of sitting in there in the middle of the day, you know. And

it's the kind of place where my father worked when I was a kid, as a

bartender. It's the kind of place where, you know, I actually spent some time

as a kid.

And when Ben was scouting the location, he went there in the middle of the

day, and he said, `OK, all of you, I want you to just be here, you know, next

week on Monday and you're going to be in the movie.' They kind of all shrugged

their shoulders and, you know, we showed up next week and there they were, you

know, just still sitting there on their stools and probably hadn't left. And

so they ended up in the movie.

DAVIES: You know, you know the director of this film very well. It's your

brother Ben Affleck. And he happened to be on FRESH AIR right after you

finished shooting this, and we asked him about what it was like directing you,

his brother. And I thought we'd maybe just listen to what he told Terry Gross

about directing you in the film.

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Uh-oh.

(Soundbite of previous FRESH AIR)

Mr. BEN AFFLECK: It was really interesting, you know, it was kind of--it's

hard, because you have to put on a different hat, you know what I mean? You

can't have this conversation with your brother the way you'd have it with your

brother if he's an actor in your movie. You have to treat him as you would

treat an actor in the movie, which sometimes means, I mean, something as

simple as trying to swallow the urge to strangle him, you know, or to be

really curt with, like, `Just because I said to do it that way, that's why!'

You know? Instead of going like, `Well, OK, that's interesting. I hear you.

Let's process what you're talking about.' So it was an exercise in

self-discipline.

But, you know, my brother, the thing that's really rewarding is that he's a

really, really good actor, and he's typically been seen in, you know, kind of

character roles as well. So I think, you know, I have the good fortune of

being able to show an audience something kind of new and surprising that's

also really good. And that's a rarity.

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: And that's Ben Affleck speaking with Terry Gross, talking about

directing our guest, his brother, Casey Affleck.

Well, Casey, now we have to turn to you. What was it like from your end?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, let me just say, first of all, he rarely swallowed

the urge to strangle me. If he felt that urge, he usually went for it. And

what's more is, I don't think I ever heard him say, `I hear you, and let me

process that.' So it's funny characterization of how we worked, but he was--I

sort of feel sort of the opposite. I don't feel like he ever had to put on a

different hat. I kind of felt like, you know, a great advantage that we had

was that we were kind of brothers who had this relationship for 32 years, that

we kind of had had every possible kind of conversation one could have, you

know. I mean, I've asked for him for advice, he's come to me for advice,

we've fought, we've helped each other, lied to each other, kept secrets, told

the truth, and, you know, we've kind of been through it all, so.

And what's more is that, you know, on top of it all, he had a fabulous way of

talking to actors, I think just because he's been an actor. You know, he

never got the megaphone and put on the boots and the scally cap and never did

like the old director thing. `Listen, pal, you're going to say your lines,

and you're going to'--you know, it was--he just said, you know, `I think it's

like this. I think you should try it like that.' Or he just--it seemed to me

like it was Ben that I'd set on a couch next to 100,000 times, watched a movie

with and talked to him about it.

DAVIES: Well, Casey Affleck, you have another film out that's getting a lot

of great reviews, and that's "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward

Robert Ford," the assassin being yourself. And this is just a fascinating

story, where you play this man who was, you know, an obsessed fan of Jesse

James who eventually becomes close to him and then does him in. It's a

fascinating story based on a historical novel. How did you prepare for this

role?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, there was a book by Ron Hansen that I read that was

beautiful, a really great kind of character study, I thought, of Robert Ford,

mostly, and Jesse James. And then I read the screenplay by Andrew Dominik,

that was just stunningly beautiful and kind of ornate and strange in its

architecture and, you know, just dialogue that just kind of like leapt from

the page. So those two the things were kind of my blueprint, because there

was nothing available about Robert Ford. There's obviously a lot available

about Jesse James; but Robert Ford, there's very little online, very little

you can find about him anywhere. There wasn't too much research that I could

do, other than learn to shoot a gun, ride a horse, and to be really

knowledgeable about the period, you know, like reading newspapers every day.

You know, every morning read a newspaper from that morning in the 1880s, just

to kind of immerse myself in the period. And that did help.

DAVIES: You know, there's one review of your performance in this that said

your metamorphosis from doormat to predator is a devastating feat of

self-transformation. I mean, it is a fascinating character you play, a guy

who is a hero worshipper, wants to be close to Jesse James, gets there, and

then eventually betrays him. And it's an interesting, I think, question,

whether Ford becomes someone different or whether the assassin and the hero

worshipper are really all part of the same package. Tell us a little bit

about this character, how you saw him. What made him want to do in this guy

he admired so much?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, it might sound strange, but I loved Robert Ford. I

read the book and I loved him, and I read the screenplay and I loved him, and

I loved playing him. There were times when I felt I hated him, and things

that he did that were really hard to do, but that's kind of like life. I find

that's true with myself. I do and say things every day that I think, `Why did

I do that? Why did I say that? You're an idiot.' So, you know, I really felt

for him. I don't think that he was an obsessed fan. I don't think that he

was a kind of celebrity-obsessed predator. I don't think that he was any of

those things.

I think he was a 19-year-old kid, grew up on a farm reading comic books about

Jesse James, who's the youngest in a big family. And no one ever thought that

he would sort of amount to anything. And he kind of felt like he had an

enormous amount of potential, that he was capable of doing something great,

that he was--and specifically, you know, he thought that he could be just like

Jesse James. And when he read these comic books, which he thought were real

stories--obviously they weren't--he thought, `Well, if I can get close to

Jesse James, you know, he's great, and he's smarter than everyone in my family

and all these people around me who tell me I'm nothing. He will recognize in

me my potential. He will make me his partner. And then there'll be comic

books written about both of us.' He just had this immature fantasy. That's

all it was.

DAVIES: Let's listen to a cut from this. This is from "The Assassination of

Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford," and our guest, Casey Affleck, you're

sitting around with Jesse James and some of the gang at dinner, and the

conversation comes up about your character, Robert Ford's, worship of Jesse

James. And you're provoked to talking about it. Let's listen.

(Soundbite of "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford")

Mr. C. AFFLECK: (As Robert Ford) Well, if you'll pardon my saying so, I

guess it is interesting the many ways you and I overlap and whatnot. I mean,

you begin with our daddies. Your daddy was a pastor of the New Hope Baptist

Church and my daddy was a pastor at the church in Excelsior Springs. You're

the youngest of three James boys, and I'm the youngest of five Ford boys.

Between Charlie and me, there's another brother, Wilbur here, with six letters

in his name. And between Frank and you, there's another brother, Robert, also

with six letters. And my Christian name is Robert, of course. You have blue

eyes, I have blue eyes. You're 5'8" tall, I'm 5'8" tall.

Mr. BRAD PITT: (As Jesse James) Ain't he something?

(Soundbite of laughter)

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: And that was Brad Pitt laughing at the end, playing Jesse James. Our

guest, Casey Affleck, was the Bob Ford, a member of his gang at the time.

What led Robert Ford to assassinate Jesse James, I mean, if he seemed to

worship and seemed to know so much about him?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, that scene that you just played is a bit of a pivotal

moment in the movie. It's funny to hear it. I've seen the movie twice. I've

never just listened to it, and it seems like a different scene to me. I just

hear different things. It's such a halting delivery of that speech, and kind

of weird. I mean, I'm smiling in that scene a little bit, kind of smirking

and shy.

DAVIES: Yes.

Mr. C. AFFLECK: And seemed like a kind of a, like, I don't know, little

girl in love or something, and just listening to it just sounds bizarre. But,

you know, I think what happens, what follows that scene is they make fun of

him. He sort of confesses that he, you know, thinks that he's just like Jesse

James, and he's embarrassed. And he gets his feelings hurt. And the next

day, he goes to the police. You know, it's just a kind of young, rash,

impetuous, silly decision because he's got such hurt feelings, that he just

lashes out by getting on his horse and going to town and telling the police

that he knows where Jesse is and he could turn him in. Now, that decision is

something he just can't undo.

Now, you know, the police know who he is, and they kind of trap him. They

don't leave him alone. You know, they say, basically, `If you don't capture

or kill Jesse James, you're going to jail.' And kind of, you know, they just

keep pressuring him and pressuring him. And he has to do this thing he never

wanted to do. He didn't want to kill Jesse James. It's not Mark David

Chapman. He's not crazy. He didn't want or think he was replacing him. You

know, he just put himself in a spot he couldn't get out of. Of course what

happens is that after he does kill him, he gets sort of the thing that he

always wanted. The whole country sees him. He's more recognizable than the

president of the United States of America. It's a really, really big deal in

the country.

DAVIES: If it's not giving away too much of the story, tell what happens in

the years after he assassinates Jesse James.

Mr. C. AFFLECK: Well, he becomes very famous. Everyone knows who he is,

mostly from this one photograph that's taken of him, and he goes around the

country. He does 800 performances reenacting the killing of Jesse James, in a

kind of theater production with him and his brother, who was there at the

murder. And his brother plays Jesse James and he plays himself. They go on

Broadway, and they reenact the murder over and over. And at first the

audiences just eat it up; you know, they love it in the way like you kind of

watch it like some of these reality shows. And then they turn against him.

The mood of the country just turns kind of really quickly and people start

throwing stuff at him on stage. They hate him. They think he's a, you know,

a traitor. And it's mostly because, I think, people are still affected by the

assassination of Lincoln. And so once the idea gets out that, `Oh, Robert

Ford is an assassin,' then everything gets out of control. You know, people

just hate him and they don't really know why.

The other is that people who kind of--opinion makers, if you will, people in

the kind of Northern, Northeastern cities, those are the only people that are

writing about Jesse James. They write the comic books and they also write the

things after he's been killed. That's where Robert Ford is doing these plays,

you know, in these big cities, these big urban areas. And they don't know

anything about Jesse James. They were never affected by him. He was just

some like comic book guy. They had never been robbed by him. They didn't

have a cousin who he killed.

You know, Jesse James was terrorizing the state, Missouri. You know, it was

people weren't--they were going around it on their way out West just because

they didn't want to go near the James gang and those outlaws. So it was

ruining the economy. It was horrible. He was really kind of hated by many,

many people out West; but in the Northeast, people just thought he was fun.

You know, they just thought it was nice; it was fun to read about this guy

from a kind of already a bygone era. So when he was killed, they made Robert

Ford the kind of two-dimensional figure in the way that they had made Jesse

James, as you had mentioned, bigger. They just sort of slotted Robert Ford

into this kind of fairy tale. You know? And he, of course, had to be the

villain because he as the guy that killed the hero. And it ruined his life.

So for the next 10 years, he was plagued by, you know, that one act. And he

had to move from town to town because people would run him out of towns. And

finally he was shot.

DAVIES: Well, a lot of folks know that you and your brother, Ben, and Matt

Damon all grew up in the same neighborhood in Cambridge, Massachusetts. What

got you interested in acting originally?

Mr. C. AFFLECK: My mother's best friend in college became a local casting

director in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Our families were pretty close. She

used to bring Ben and me in with her children to be extras in movies, when we

were in school, just little kids, 10 years old. And I didn't really care much

about the movies. I just thought, like, `Well, this is a day off from school.

I can graze over, you know, the craft service table for eight hours.' There's

more candy than I'd ever gotten to eat. And, you know, you walk away with 15

bucks and which my mom let me keep. So it was a fortune, and it was a lot of

fun.

So then she would bring us in for like local, you know, commercials, like the

weather commercial at the local news station and that kind of thing, and I

kind of thought, like, `Wow, I'm incredible. I'm getting every part I

audition for.' It turns out that it was, I think she was only bringing me in.

I was the only person auditioning. I was the only kid who had a mom that

would let them like take two days off from school and go stand under a rain

machine to do an ad for the weather guy. But that gave me some confidence.

DAVIES: You were good, yeah.

Mr. C. AFFLECK: And then I--mostly, you know, the truth is, it wasn't until

high school that there was a guy named Gerry Speca, who was one of those

teachers you kind of just hope your kid gets once in his 12 years of

education. And Ben and Matt and I and a bunch of other working, professional,

talented actors--even a guy that's in "Gone Baby Gone," he plays the child

molester Corwin Earle--he had all of us as students, and he sort of inspired

us all. I was playing baseball and, you know, throwing rocks around in the

street. I didn't have any--I didn't want to be an actor. And it wasn't

until, you know, one summer I went and did the summer musical, mostly because

it was like 19 girls and it was me and that's it, and you kind of got to spend

the summer that way, and that seemed a lot better than like sitting on the

bench in the, you know, baseball summer league--because I was smaller than

everyone by that time. So I said, `Well, I'm going to go do this.' Turns out

I was tone deaf, they cut all my solos, but it was a lot of fun.

And then the next year, I signed up for the drama class, and I found that guy

Gerry Speca, and I've never really wanted to do anything else since then. And

I think that Matt and Ben kind of both feel the same way, had the same

experience with Gerry.

DAVIES: Thanks so much for spending some time with us, Casey Affleck.

Mr. C. AFFLECK. My pleasure. Thank you.

DAVIES: Actor Casey Affleck recorded last fall. His films "The Assassination

of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford" and "Gone Baby Gone" are now out on

DVD.

Here's some music from the soundtrack of "The Assassination of Jesse James,"

written by Nick Cave. He'll be Terry's guest on Monday.

I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Linguist Geoff Nunberg on the word "elite"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, filling in for Terry Gross.

Barack Obama's bowling misadventures and remarks about bitter voters, Hillary

Clinton's whiskey shots and gun stories, John McCain's family money--once

again a presidential campaign has come to who's elite and who isn't. Our

linguist Geoff Nunberg explains the history of the E word and its cultural

evolution.

Mr. GEOFF NUNBERG: People are always splitting off new meanings for words,

but every once in awhile they'll smoosh together two old ones. As with other

kinds of inbreeding, the process can produce monsters. Take the curious,

recent development of the noun elite. Until not long ago, it was a barely

nativized French word that still wore a jaunty acute accent on its E. Now

it's a word that can drive items like Iraq and immigration to the bottom of

the network's debate agenda.

Elite use to have two distinct meanings. It could be a lah-dee-dah word for

the upper crust, what people use to call the bon ton. Or, more

consequentially, it could denote the interlocking command structure of

society, that the sociologist C. Wright Mills referred to in the title of his

classic 1956 book "The Power Elite." As Mills described them, those were the

people who rule the big corporations, run the machinery of the state and

direct the military establishment.

Until a few decades ago, the two senses of elite rarely even nodded to each

other. The first appeared only in society pages and the names of pastry

shops. The second showed up only in political dispatches and sociology

journals. The blurring of those two senses was first audible in the 1960s,

when Spiro Agnew first put the phrase "media elite" into wide circulation and

joined it with descriptions like "effete snobs," which suggested the social

meaning of the word.

But the new meaning of elite didn't really start to emerge until the summer of

1992, when Vice President Dan Quayle sparked a national controversy by

denouncing Candice Bergen's TV character Murphy Brown for having a child out

of wedlock. Quayle put the blame on a cultural elite who were mocking

ordinary Americans in newsrooms, sitcom studios and faculty lounges all over

America. `We have two cultures,' he said, `the cultural elite and the rest of

us.'

Those attacks weren't sufficient to save the Bush-Quayle ticket in the fall

elections, but they did put the E word at the center of national attention.

When he was asked who exactly made up the cultural elite, Quayle answered

coyly, `They know who they are.' But Newsweek obligingly provided a list of

its 100 most prominent members, which evenhandedly included both poster child

liberals like Bill Moyers, Frank Rich and Oprah, and conservatives like

William Bennett, George Will and Lynne Cheney.

By any reasonable measure of cultural influence, those were all

uncontroversial calls; but by then the noun elite had been sent spinning

inexorably leftward. It wasn't just that it was now exclusively prefixed by

"liberal" and that it suggested a seditious taste in cheese and beverages;

even the job descriptions of the elite had changed so that the qualifier

"cultural" had come to seem redundant.

In the British media, you still see elite used predominantly to refer to

economic and business leaders, whether you look at the left-wing Guardian or

Rupert Murdoch's Times of London. But on Murdoch's Fox News, references to

the media elite outnumber references to the business and corporate elite by

40-to-1. And the disproportion's only slightly less dramatic on CNN.

When Americans hear elite these days, they are less likely to think of the

managers and politicians who inhabit the corridors of power than of the

celebrities, academics and journalists who lodge in its outer burroughs. It

remained only for the noun elite to undergo its final democratization, where

it was emptied of its last connections to social position or to actual wealth

or power. All that was left of its original meanings was the implication of

insufferable pretension and an unwarranted sense of entitlement.

As the conservative radio host Laura Ingraham explains it in her book "Shut Up

and Sing," elite Americans are defined not so much by class or wealth or

position as they are by a general outlook. Their core belief is that they're

superior to we, the people. They think we're stupid. They think where we

live is stupid. They think our SUVs are stupid. They think our guns are

stupid.

That broadened meaning of elite can create some confusion for liberals who

haven't quite cottoned to it. They're apt to get indignant when they hear

elite pronounced with a sneer by people who would have unquestionably

qualified for the label under its traditional definition. And they may be

puzzled by the expansive use of "we," that modern critics of elites tend to

fall into when they're talking about nonelite Americans.

How does a Connecticut-raised, Ivy-educated lawyer like Ingraham get to share

a first person plural pronoun with a working-class deer hunter from western

Pennsylvania? For that matter, what are we suppose to make of that pronoun we

when we hear the quintessential blue state conservative David Brooks asking,

`Is Barack Obama somebody who doesn't know anything about the way the American

people actually live, or does he actually get the way we live?' I mean, if you

give Brooks that we, who's the "they" suppose to be? But then if you don't

have to have money, power or influence to qualify as elite, it follows that

having those things doesn't necessarily disqualify you from being one of the

rest of us, so long as you can knock back a shot occasionally and don't stop

channelling your inner...(unintelligible).

The crucial thing, as Barack Obama learned, is not to be caught seeming to be

out of touch, a phrase that Google News paired with his name in more than 3500

stories after the "Bittergate" episode. Summer wherever you like; but if you

don't want to be described as elite, you'd better know who Dale Earnhardt Jr.

is.

DAVIES: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist who teaches at the School of Information

at the University of California at Berkeley.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Jerry Seinfeld discusses career and new movie "Bee

Movie"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

It's been nine years since Jerry Seinfeld made the last episode of his hit TV

series. At 53, he's now married and has three children, and last fall he

unveiled the project he had spent much of the previous four years developing:

the animated film "Bee Movie." "Bee Movie," which Seinfeld co-wrote and stars

in, along with Renee Zellweger and Matthew Broderick, is now out on DVD. But

even before "Bee Movie" was released, Seinfeld had returned to his original

love, stand-up comedy. He has upcoming dates in nine cities. I spoke to

Jerry Seinfeld last fall, when "Bee Movie" was released in theaters.

When you do stand-up, I mean, nothing is more autonomous than the stand-up

comedian. It's his act and the feedback is immediately.

Mr. JERRY SEINFELD: Mm-hmm. Right.

DAVIES: I mean, you go in, you bomb, whatever. You kill.

Mr. SEINFELD: Maybe doing stand-up alone, by yourself, could be more

autonomous.

DAVIES: Possibly. And the feedback would be even more immediate. Right?

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. That's right.

DAVIES: But, you know, a movie takes years. It begins with endless meetings.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: There's endless editing.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. Endless.

DAVIES: How did you adjust to the pace of it?

Mr. SEINFELD: I didn't adjust very well, to be honest with you. It kind of

goes against my natural instinct, which is, `I want to hear tonight if this is

any funny or not.' You have test screenings, and it was just like being

strapped down for four years. You know, I know a lot of other comedy writers

and comedians that would look at me and they would say, `You're still working

on that movie?'

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And I go, `Yeah, we're still going.' I mean, four years, it's

like I know people that wrote movies, got them produced, edited, released,

went on to other movies.

DAVIES: I want to talk a little bit about your stand-up, which has, you know,

been your core for years. And I thought--and I wanted to play a clip.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And this is not you at a club. It's actually a clip from an

appearance on "Letterman," and I got it from the documentary that you did,

"Comedian."

Mr. SEINFELD: Uh-huh.

DAVIES: And the context here is you've--this is after the show has been off

the air for awhile and you're coming back, and it's a TV appearance. I don't

know if you remember this. Let's listen.

(Soundbite of "Comedian")

(Soundbite of audience clapping)

Mr. SEINFELD: Thank you. Thank you, I appreciate that. I totally

appreciate what you're saying. I do. But the question is this: What have I

been doing?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SEINFELD: Everybody says to me, `Hey, you don't do the show anymore.

What do you do?' I'll tell you what do I do: nothing.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah, I know what you're thinking. `That sounds pretty good.'

You're thinking, `I might like to do nothing myself.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SEINFELD: Well, let me tell you, doing nothing is not as easy as it

looks. You have to be careful. Because the idea of doing anything, which

could easily lead to doing something, that would cut into your nothing, and

that would force me to have to drop everything.

(Soundbite of laughter and applause)

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: And that's Jerry Seinfeld, our guest, from the appearance on the

David Letterman show many years ago.

You know, you know what I love about that clip is that you got four or five

really good laughs out of--what?--one joke.

Mr. SEINFELD: It was nothing.

DAVIES: Hardly a joke.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah.

DAVIES: I mean, and it's all--it just--it shows all those years in clubs,

you've just got the pacing and the punch exactly where you want it.

Mr. SEINFELD: Thank you.

DAVIES: And I mean, I know you spent all those years--you made your first

appearance on "The Tonight Show" in 1981.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And throughout the '80s you were building a reputation as a stand-up

at a time when a lot of--there are a lot of other comedians that are out there

that are maybe getting more attention by being outrageous or profane or kind

of using props or crazy characters. And I wonder, you know, kind of gave them

an identity and a hook.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: Did you ever try that stuff or were you ever tempted to try it?

Mr. SEINFELD: No, I never was. And I always felt like I was very much a

hookless comedian and I would always be hookless. And that, I thought, maybe

that's my hook, you know, that I just don't have anything that you latch onto

as, `He's the guy who does this or looks like this.' But it wouldn't have felt

right anyway. I mean, that was kind of the joke about the show, was that it

was about nothing.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: But what it really was about was the way we executed it. And

it's the same thing as what my stand-up is about. It's the same thing as what

that joke was about. What is that joke? It's taking the word "nothing,"

"something," "everything" and "anything" and assembling it into a thought that

makes sense. And so that's really what I like to do, is I'm more into the

execution than I am anything--other aspects of it. I mean, I don't even care

about being famous or being, you know--I just enjoy the doing of the thing.

DAVIES: Well, you know, in the documentary "Comedian," which is, you know,

for those of you haven't seen it, it's you going back to stand-up after having

done the show.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: Kind of getting back into it. And there's this moment in it that I

really love where you've sort of built the act up toward you've not got a good

50 minutes.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And you do an appearance, I think, at a club in Washington, DC. And

it seems to have gone pretty well, but after it you're not satisfied.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And you're saying, `God, it's just so hard to really feel

comfortable.' And you're kind of bemoaning whether you really hit it...

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: ...as you're packing your stuff and getting into your private jet--or

what looks like you private jet.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah.

DAVIES: And so what's fascinating is we have you, who have all that money and

success, that insist on subjecting yourself to this ego-battering process of

getting back in live clubs.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: You always want to do that. Why?

Mr. SEINFELD: You know, it's just that feeling of not cheating that is the,

I think, the best feeling in life. I didn't cheat at that. And stand-up is

the only thing that I knew that I could be sure that I--if I was doing it and

audiences were responding well, that I wasn't cheating. Because there is no

way to cheating in stand-up. It's the nakedest, purest thing in the world.

But, you, you know, I could have gone into a movie. Someone would have said,

`We have a great idea for a movie for you.' And they could have put me in a

movie and promoted the movie, and the movie did this, and I would never know,

`Was that any good or not?'

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: You know, `Well, the director didn't handle you right.' Or,

`It wasn't promoted the way it should have been.' There's always a million

excuses. There's no excuses in stand-up. So after all of that experience of

Hollywood and television and everything that the show did, I just wanted to

get back to something that I knew what was right and wrong, and what was black

and white. And it's a very black and white world, and that was calming to me,

and that would make me feel--I just never wanted to feel like I was skating on

a reputation or, you know.

DAVIES: And you can't skate on a reputation at a live club?

Mr. SEINFELD: No, absolutely not.

DAVIES: Even if you're Jerry Seinfeld?

Mr. SEINFELD: Even if you're Jerry Seinfeld. Maybe a couple of minutes.

The may give you three or four free minutes at the top, but after a while no

one laughs at a reputation. It's not funny.

DAVIES: And did you get where you wanted to be? Did you get comfortable?

Mr. SEINFELD: I did finally. It took about four or five years of working.

And I've lost it a little bit now doing the movie, and then I'm going to go

back. But it's kind of a tennis game. A stand-up act is like a tennis game.

I mean, even if you're good, you've got to keep playing if you want to keep

that game at a certain point.

DAVIES: And you're sure you want to keep playing?

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. I love the simplicity of it. I love the purity of it.

It's just--this is what, I mean, all this work that we went in the movie, I

mean--to make an animated movie, the infrastructure of DreamWorks is a billion

dollars. That's what it costs just to have the machines to make one of these

things. And then the years of work. And what is it all for? Its so that

when we put it in front of the audience, you hear a laugh.

DAVIES: Same thing as standing up and telling a joke, right?

Mr. SEINFELD: Same thing. Same thing. So, you know, I like--it's the

difference between, you know, you say you like the water, well, you can be the

captain of a ship or you can surf.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And stand-up is like surfing, you're just right there. Right

there with it.

DAVIES: Well, since you were last on FRESH AIR, you did this TV series, which

kind of took off.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. Right.

DAVIES: And as sort of a measure of its cultural reach, my wife had a career

change this year and she had about six weeks between her old job and when she

began her new life as a resident in psychiatry, which was in June and July.

And I began referring to this time, which she had looked forward to so much,

as her "Summer of George." Which, for folks who may not recall, was the

"Seinfeld" episode where George Costanza has a summer off and he buys an easy

chair with a built in refrigerator.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: And what's funny about it is that, you know, when I kind of came up

with that phrase, everybody in my family laughed and talked about it. She

would talk about it to her friends. They all knew exactly what we were

talking about.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: And in a way, that series, which you haven't made a new episode in

nine years now, but it's all over television...

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: ...is sort of this book of life. I mean, people use moments and

lines from that series to describe what's going on in their lives. You're

aware of this phenomenon.

Mr. SEINFELD: I am, but I don't get it. I mean, it mystifies me as much as

you. And I'm only happy that it's doing something for somebody.

DAVIES: It doesn't mystify me because you're capturing stuff that we all kind

of recognize.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. But doesn't--isn't every--why is it different in other

comedy shows? Why can't you name other comedy shows? You know, Larry David

said to me the other day that this was the first show where people would say,

`Well, that's a "Seinfeld" episode,' about something that, `I had a day today

that sounds like a "Seinfeld" episode.' That our show was, for some reason,

lent people to think like that about their own lives. Because I guess maybe

one of the reasons is we stayed so close to people's real lives. We tried to,

anyway, as much as we could, aside from, you know, hitting golf balls into the

blowhole of a whale.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And maybe that's why people can analogize to it or from it.

DAVIES: How did you know when it was time for the show to end?

Mr. SEINFELD: From my stage act. The stage act, you know, I had been doing

comedy, let's see, about 23 years at that time. And you start to know on

stage when to get off. There's just this feeling that you develop from years

and years of doing it. You just feel that we're getting--everyone's really

having a good time and I think in another few minutes this is going to start

to get old. `Good night, everybody.'

DAVIES: Hm.

Mr. SEINFELD: And everyone's happy. And I'm sure you've had the experience.

Everyone has had the experience of going to a movie that you love but for some

reason they just make it 15 minutes longer than it really needed to be. And

the change in your feeling about the movie because of that little 15

minutes--and it may not even be a bad 15 minutes. It's just proportions, you

know. I guess it's a function of art and economy that economy is essential to

all good art. And I thought, `Let's'--even thought we had done a lot, nine

years, 180 episodes, I thought, `We can't do one too many or it's going to

taint the whole thing.' So it was more the energy I felt around the show

itself.

DAVIES: That's what's interesting, because on stage you've got that--you said

you have that sense from the audience...

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: ...that you've honed over the years.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. It was in the office. It was in the office of the

show. The writers would come in, and the way they would look at me and when

they would say, `So I had a thought that maybe Kramer would, you know, become

friends with a penguin or something.' You know? And I just, I would hear it

in their voice, `They're not as excited. This is getting old.' And I thought,

`Well, if it's happening here, the audience is next.'

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And, you know, I had a meeting with Jack Welch and he showed

me--it was a hilarious meeting where he...

DAVIES: It was with the chairman of...

Mr. SEINFELD: The chairman of GE at the time.

DAVIES: Right. Which owned NBC.

Mr. SEINFELD: And they owned NBC. And he had these charts of the ratings

and the demographics of the show. And every chart showed the numbers going

up. He said, `You have improved your audience from the eighth season to the

ninth. The ninth is stronger than the eighth.' So it was all backwards. You

know, usually you go in there, you try and tell them why you deserve more

money and why the show should be kept on.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And it was the--everything was backwards. I'm telling him,

`No, no, no. We shouldn't go anymore.' He says, `No, no, no. You should.

I'll give you a raise. I'll give you more money.' You know, I said, `I don't

want money. I want the audience to have this thing.' It was kind of like--and

I don't mean to compare myself in any way, shape or form to The Beatles--but

when The Beatles ended, it was so sudden and it made what they did somehow

more valuable.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: Because it just suddenly was over, and that's it. That's the

complete set. You know, nine years, 12 albums, whatever it is, that's it. So

I kind of took from that, `I want to try and do that.'

DAVIES: You know, it's funny. I can't help but think of the episode in the

series when George Costanza adopts this posture and in a meeting gets the one

funny line--cracks off a line that breaks the room up.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: And he said, `That's it. I'm done. I'm out of here.'

Mr. SEINFELD: That's where the idea came from.

DAVIES: Jerry Seinfeld, recorded in October. His animated film "Bee Movie"

is out on DVD.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Film critic David Edelstein on "Standard Operating

Procedure"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

Errol Morris, the director of "A Thin Blue Line," "Dr. Death" and "Fog of

War," has a new documentary called "Standard Operating Procedure." Morris uses

on-screen interviews, stylized reenactments and special effects to present his

perspective on the scandal over the Abu Ghraib prison photos. Film critic

David Edelstein has this review.

Mr. DAVID EDELSTEIN: Pictures don't lie. That's what Special Agent Brent

Pack tells Errol Morris' camera in "Standard Operating Procedure." And the

film suggests that he's right--and wrong.

Pack help convict several Abu Ghraib guards on the evidence of widely

circulated photos, the ones from that infamous night in 2003 in the prison

basement, when naked Iraqis were forced to touch themselves and straddle one

another in a human pyramid. And when when a close-cropped, diminutive

gargoyle named Lynndie England led a naked Iraqi on a leash--nightmare stuff

seared into the public's imagination. But the question Morris poses is just

as haunting. If those pictures exposed some truths about Abu Ghraib, did they

conceal other, even larger ones?

Morris has hold of a huge subject, one in which politics and art bleed

together. Using his own standard operating procedure--fixed camera

interviews, slow motion reenactments, a busy and hypnotic score by Danny

Elfman--the director keeps looping back to what happened outside the frame,

before and after the photos and a video were shot. Over and over he shows us

the infamous images, then effectively subverts them by giving us the context.

Lynndie England speaks, filmed like her fellow ex-soldiers, in the standard

Errol Morris style: close-up against a neutral background. You wouldn't

recognize her. Her face has filled out, and her hair is dark and abundant.

She was demonized in the media, dishonorably discharged and imprisoned, one of

a group that Donald Rumsfeld dismissed as a few bad apples. But this bad

apple is disconcertingly human. England was prodded into taking that leash by

a man she loved and whose baby she'd have, Charles Graner, the Busby Berkeley

of the Abu Ghraib dance macabre. She wasn't yanking that Iraqi, she says, the

leash is slack. And what happened that night was typical, not extraordinary.

(Soundbite of "Standard Operating Procedure")

Ms. LYNNDIE ENGLAND: We didn't kill them. We didn't cut their heads off.

We didn't shoot them. We didn't cut them and let them bleed to death. We

just did what we were told to soften them up for interrogation, and we were

told to do anything short of killing them. We'd make them stand in awkward

positions for hours at a time to stress them out and to strain them. And we

would have them crawl up and down the tier. We'd pour cold water on them.

(End of soundbite)

Mr. EDELSTEIN: In films like "Dr. Death" and "A Thin Blue Line," Morris

makes his subjects look like specimens in a jar. He lets them go on and on

until they hang themselves. "Standard Operating Procedure" has a less

detached, less ironic, more sympathetic vantage. As Morris weaves together

the accounts of the Abu Ghraib participants, it's as if he's using his own

camera to liberate them from someone else's. You can believe Lynndie England

or not, but there was more in those photos than met the lens.

Even with his disturbing reenactments, it's possible that Morris errs on the

side of sympathy. What are we to make of the guard Sabrina Harman's broad

smile astride a human pyramid? She tells Morris that when you pose for a

photo, you want to smile. Well, yes--and no. But she reads from a letter to

her partner, Kelly, in which her shame is right there on the surface.

The world of Abu Ghraib these ex-soldiers depict is morally upending. We see

photos and hear accounts of an Iraqi found dead after a brutal interrogation.

He's zipped into a body bag, iced down, then dragged to the showers so he'd

look, despite his horrific bruises, as if he'd keeled over from a heart

attack. It's the stuff of grisly farce.

Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, who had responsibility for the prison,

supplies a wider context. She recalls Rumsfeld underlings directing guards

to, quote, "treat the prisoners like dogs," and was relieved of command when

the world saw them doing just that.

But for a more overarching view of the administration's strategy, I recommend

Alex Gibney's Oscar winning "Taxi to the Dark Side." Gibney depicts the

directives as purposefully vague, relentless pressure for results, plus what

one official calls a fog of ambiguity regarding what is and is not permitted.

See "Standard Operating Procedure" for its faces, its riveting narrative and

for the monkey wrench Morris throws into the cogs of our perceptions. The

special agent who testified against the guards, Brent Pack, says, `A picture

is worth a thousand words.' Maybe so, but the movie asks, `Which words? Whose

words?'

DAVIES: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.