The Man Working To Reverse-Engineer Your Brain.

Our brains are filled with billions of neurons. Neuroscientist Sebastian Seung explains how mapping out the connections between those neurons might be the key to understanding the basis of things like personality, memory, perception, ideas and mental illness.

Other segments from the episode on February 29, 2012

Transcript

February 29, 2012

Guests: Nick Flynn & Paul Weitz â Sebastian Seung

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, in for Terry Gross, who's off this week. Imagine working in a homeless shelter and finding one day that your father has come in from the street for a bed. That happened to writer Nick Flynn when he was in his 20s, and he wrote about it in a memoir with a title we can translate as "Another BS Night in Suck City."

The story is now a movie called "Being Flynn," starring Paul Dano as the young Nick Flynn and Robert De Niro as his father Jonathan. Jonathan Flynn spent most of his life as an alcoholic who worked odd jobs and spent time in prison, but always considered himself a great writer.

Our guests today are Nick Flynn and Paul Weitz, who directed "Being Flynn." Weitz directed the film "American Pie" with his brother Chris. They also directed and wrote the screenplay for "About a Boy," adapted from a novel by Nick Hornby.

Nick Flynn is a successful poet and has written a second memoir called "The Ticking is The Bomb." Here's a scene from "Being Flynn," in which Nick's father, played by Robert De Niro, meets Nick, played by Paul Dano.

(SOUNDBITE OF MOVIE, "BEING FLYNN")

PAUL DANO: (As Paul Flynn) Wait, so you drive a taxi?

ROBERT DE NIRO: (As Jonathan Flynn) Well, it's an extra way of learning about all different kinds of people. And what's your vocation?

DANO: (As Paul) My vocation, uh, I've done lots of different jobs.

NIRO: (As Jonathan) I always thought you'd end up a writer like your old man.

DANO: (As Paul) Actually, I do write, you know, sometimes. I try.

NIRO: (As Jonathan) Well, there's no such thing as trying to write. One writes or one doesn't, and you have to take every opportunity to practice your craft. Anyway, I know you've inherited some writing talent from me because I am a truly great writer. I'm going to show you something, a letter from Viking Press. You've heard of Viking Press, haven't you?

DANO: (As Paul) Yeah.

NIRO: (As Jonathan) Look at this. Look at that phrase there.

DANO: (As Paul) Your book is a virtuoso display of personality, unfortunately its dosage would kill hardier readers than we have here.

NIRO: (As Jonathan) Virtuoso display - Viking Press.

DAVIES: Well, Paul Weitz and Nick Flynn, welcome to FRESH AIR.

NICK FLYNN: Thanks for having us.

DAVIES: Nick, let's begin with you. You grew up without really knowing your dad, right? He left when you were a baby. What was your image of him, growing up?

FLYNN: There wasn't much image. I barely saw a photograph of him. My mother didn't talk about him. There would be occasionally - on Christmases, there would be - a gift would appear, somehow, maybe in the mail or maybe left at my grandmother's house. And - but slowly, when I became a teenager, he sort of came more into my life because he got sent to federal prison for something like robbing banks and began writing me letters from prison.

So that's sort of - when I was about 15 I began to know a little more about him.

DAVIES: And what were those letters like?

FLYNN: Occasionally they were, sort of, profound and kind of filled with a certain kind of insight. There - advice on how to be a writer, even though he knew nothing about me and didn't know I wanted to be a writer, and maybe I didn't, even at that point. And just about how to live in the world.

But also they were a little loopy, too, a little delusional and crazy, and they got crazier as they went on, just in - he would Xerox a lot of letters. He would send the same letter, sometimes, to some famous people like Ted Kennedy. He was someone who wrote to a lot, and he would Xerox that letter and send it back to me.

So there began to be sort of Xeroxes of Xeroxes. He sent me Ted Kennedy's letter to him, which were, sort of, form letters.

DAVIES: The idea was to impress you with his importance?

FLYNN: I believe so, yeah, yeah. Many of the letters did end with or begin with, you know, soon, very soon I shall be known. Like he really sort of put all his chips into the idea of becoming famous, and he's be famous through his writing. I mean, that was what - where his fame would rest, would be in his writing.

DAVIES: Did you write him back?

FLYNN: I never did. No, I never wrote him back. I wrote him back once, once when he was homeless. You know, years later, I was in my late 20s, and I wrote him a letter once, and it - he ended up promptly Xeroxing it and sending it around the country. So I felt kind of awkward about that.

DAVIES: Now, I know from the memoir you were long interested in writing. I mean, you had projects with friends of yours. Why didn't you think of writing your dad back?

FLYNN: It was mostly out of respect for my mother, I believe. She - there was clearly, you know, a deep river of bad blood between them, and I think if I expressed interest in him, it felt like it would somehow hurt her in some way. So it was more to protect her, I think. I think to suggest that I needed or that I somehow - that that presence was lacking in my life, which I don't even know if that would be true, that it was, I felt somehow would hurt her, I think.

I think that's why, the main reason.

DAVIES: I guess you were about 16 when he went into prison. He served a couple of years, and then when he got out, did the letters keep coming? Did you have any contact or sense of where he was?

FLYNN: Yeah, letters came - they began, once he got out of prison, the letters became - they came out now on letterhead. He somehow created a fake corporation for himself while in prison, something called the Fact Foundation of America, where he was - now he was writing about his experiences in prison and comparing himself to Solzhenitsyn's experience in the Russian gulag.

And, you know, it almost became - he became almost more self-aggrandized after prison with this fake company called the Fact Foundation of America. So yeah, the letters kept coming, yeah.

DAVIES: OK, so as you get into your 20s, you're in Boston, and you start working at a homeless shelter. Why do you think you found yourself working there?

FLYNN: Yeah, I began working at the Pine Street Inn, you know, a homeless shelter in Boston, when I was 24. And it was about two years after my mother took her own life, and I was young and quite lost, grieving. And I'm not sure exactly why working at a homeless shelter made sense to me, why that would be the place to go, except that I think I needed to be, you know, perhaps to immerse myself in some sort of larger real-life situation, to get me out of the sort of the cage of my mind, in some way, and, you know, however I was torturing myself. To be around other people who were struggling and to sort of maybe find a purpose for my life.

DAVIES: And when you were 24, when you started working with the homeless, did you know that your father was then on the street?

FLYNN: Yeah, when I was 24, my father wasn't on the street. He - when I began working at the shelter, my father was driving a cab and paying his bills, and he wouldn't end up homeless for three years after I'd been at the shelter, so...

DAVIES: So Paul Weitz, you read Nick Flynn's memoir about his experiences. What made you want to adapt it for a film?

PAUL WEITZ: Aside from the beautiful, poetic details of the story and its presentation in the book, it boiled down to a couple of themes, which were really central to me. One of which was whether we're fated to become our parents and eventually how much of their flaws do we have to own in order to move on with our lives. And the second of which was the relation between creativity and ego, in that it's about Nick's father, Jonathan Flynn, played by Robert De Niro, states in the beginning of the movie that he's one of three great writers in America has produced: Mark Twain, J.D. Salinger and Jonathan Flynn.

He had this vision of himself as a great artist. And while that ego must have consumed him in some way, also it was also interesting that Nick later on said that that sense of self and differentiation from the people who he was eventually living with in the shelter, probably is what helped him survive and not end up either living in a shelter permanently or dying out on the street.

DAVIES: Robert De Niro plays Nick's father, Jonathan Flynn, in this film. Paul Weitz, how did De Niro get involved in this project?

WEITZ: He got involved very early on, and then stuck with the film over the course of six or seven years, when it was sort of bouncing from studio to studio. His attitude towards the film was so pure, I feel, throughout, and it was kind of exemplified by a month before shooting, there was a section of the film where - after Jonathan has been kicked out of Pine Street Inn for essentially being out of control, he is out on the street.

And I needed some sequences with De Niro walking around in the snow. And we were shooting in New York - about to shoot in New York, and you never know when it's going to snow. And a month before we were supposed to start shooting, I got a weather report that it was going to blizzard the next day.

So I called De Niro up, and I said: What are you doing tomorrow? And he said: Why are you asking? And I said: Well, how do you feel about jumping in a car and getting whatever costume we have and going and shooting with me?

So, very similar to a student film, I went out with Robert De Niro and a cameraman, and we hopped all around the city during this blizzard, largely in the financial district, because I knew people would pay no attention to the camera or to Robert De Niro, they just wanted to get to work.

And we shot something that was very integral to the film. And it happened to be Nick's birthday, Nick Flynn's birthday on that day, and he was - he flew back that afternoon from Houston, where he teaches, and arrived as we were doing our last stolen shot with De Niro.

DAVIES: You know, it's interesting you mention the scenes where he's walking around, you know, and the snow is beginning to fall. It's a fresh snow, you can tell. You have a sense that it's like the first serious snowfall of the winter. And I think one of the things that the film really captures so vividly is the transition of somebody who's an alcoholic, from being employed and functioning to somebody who is on the street, who, you know, loses a job, loses an apartment and eventually accepts the fact that he is going to have to sleep outside tonight.

Do you want to just kind of explain how you shot that and got that?

WEITZ: Actually, having the script for so long, and De Niro having the script for so long, was really beneficial. Because literally, you're - you can be hop-scotching between a scene from the end of the movie and the beginning of the movie, but everybody has to know exactly where they are in the characters' journey.

I felt like Bob locked down on the character in a way that was quite moving to me, because I was very conscious of working with somebody who was one of the pillars of an art form on a character that was extremely complicated. And it was a huge benefit to me and to De Niro to have Nick around because Nick, we could look over at him and say, is this hogwash what we're doing?

So Nick would give us very specific things, such as how Bob ought to duct-tape his sleeves to keep the cold from getting in or how he would go into a bus shelter and grab wads of toilet paper to stuff under the ears of his hat for added warmth.

De Niro clearly worshipped some idea of reality or truth. Also, there was a very telling moment when De Niro and Nick and I went to visit Nick's dad in Boston. And when we sat down to meet him, the real Jonathan Flynn, as opposed to being at all intimidated by meeting Robert De Niro, looked over and said: So, do you think you can pull this off?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

WEITZ: And Nick said: Well, dad, he's a very well-respected actor, he was in "The Godfather," et cetera. And Jonathan said: I hear you're quite good, but are you going to be able to play me?

DAVIES: Wow.

WEITZ: And I kind of feel that that was license for Bob to pay due respect to this character's utter self-confidence. And it was a very odd irony that while Jonathan Flynn never had this masterpiece he was working on for decades published, he has now had a memoir written largely about him and is being played in a movie by Robert De Niro. So there's a point at which one can't tell whether his delusions have been borne true or not.

DAVIES: Right. What was it he kept saying, soon I will be known? And now he is.

WEITZ: That's right.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

DAVIES: I thought we would hear a - we have a little bit of sound of Jonathan Flynn, the real Jonathan Flynn. And this is from an episode of "This American Life," which, you know, Nick Flynn, you participated in some years ago. And I know that, Nick, you went and shot a lot of video of your father. And so this is from one of those videos. So I thought we would just hear a bit of this.

This is - I believe the context here is that he's talking about himself, which I guess is probably his favorite subject, and he's listing places where he has been imprisoned, you know, and kind of comparing himself to other famous writers who wrote from prison. Again, Jonathan Flynn, let's listen.

(SOUNDBITE OF "THIS AMERICAN LIFE")

JONATHAN FLYNN: Leavenworth; Lewisburg; Atlanta; Marion, Illinois, which was built to replace Alcatraz. I mean, I was there, and I had the pleasure - I mean, the pleasure speaking as a Solzhenitsyn. I mean, I wanted to know what the (beep) I was writing about. I'm thinking, Jesus, Solzhenitsyn's going to jump with envy when he sees this (beep) story. Well, he and Dostoevsky both wrote about their adventures in Russian prisons, heavily.

DAVIES: And that is Jonathan Flynn, the father of our guest, Nick Flynn. That tape comes to us courtesy of "This American Life," from WBEZ in Chicago.

So Nick, let's talk about your father actually becoming a client, or I guess a guest you would call him, at the Pine Street homeless center where you were working. You were aware at some point that he had lost his job, lost his place and was on the street. Did you think he would show up there eventually?

FLYNN: You know, it's almost - that's one of the big questions of the book, whether when I began working at the shelter, even, when I was 24, you know, even though my father wouldn't get evicted for three more years, until I was 27, whether I went there in some - for some deeper reason that was unknown to me, to be around men that were like him, that were sort of - you know, my father was always marginal.

And he probably had slept on people's couches a lot. He probably had slept in his cab on occasions. You know, he was an alcoholic and kind of wild and not that grounded.

But, you know, I didn't go there on any conscious level. I didn't begin working there on any conscious level to meet my father. And so that's sort of the great cosmic joke is that, you know, even if I went to find people, to be around men that were like my father, like you'd never expect actually the real father to show up.

But then - and, you know, the movie, I think, you know, Paul's script and the movie, you know, tracks it pretty well or accurately, that at one point I got a phone call that - from my father who I hadn't talked to in years - saying that he was getting evicted. And I went to meet him, and that's when I went to meet him, and we sort of had that in the film, you know, going to meet him in his apartment on Beacon Hill.

And then helping him move his stuff into storage and then, you know, some months later, he ends up coming through the doors. And I think, you know, once he got evicted, I'm sure it was in the back of my mind, or somewhere, maybe it was - I can't exactly remember, but maybe it was in the forefront of my mind - that he could walk through the door at any moment.

I don't think we put it in the film that in the middle - after two months or so, I actually saw him sleeping outside. It's in the book. I don't believe that's in the film. I see him sleeping outside, and then maybe a couple months after that, he shows up at the shelter.

So I sort of - you know, there were beats along the way that, you know, led him into the shelter.

DAVIES: That's Nick Flynn. His memoir is being republished as "Being Flynn." That's also a movie starring Robert De Niro and directed by our other guest, Paul Weitz. We'll talk more after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: We're speaking with Paul Weitz, who directed the new film "About Flynn," based on a memoir by our other guest, Nick Flynn. When we left off, Nick was explaining that when he was working at a Boston homeless shelter in the 1980s, his father Jonathan walked in looking for help.

Take us back to that moment if you can. I mean, what was your reaction when you saw your father there to get a room?

FLYNN: When I showed up to work the day that he appeared at the shelter, he'd already been there. He had been there and signed up for a bed. So my supervisor took me aside and told me that someone had come to the door, claiming to be my father, looking for a bed.

And, you know, I knew that it was really my father. And the supervisor, you know, asked. He said: You can just take the night off. You don't have to be here. But, you know, I chose to stay there that night. You know, so I sat in his office for a little while, I waited, I went back to - I went to work.

A couple hours later, you know, we opened the doors, people come in. We give them dinner. They get their bed tickets, and they go to bed. And at some point my father came in. And so, you know, there was many steps along the way. I mean, so the emotions I felt, they were sort of more of a river of emotions.

DAVIES: Can you take a moment in, like, the days that followed when he became a regular there that you remember, that captures something about where the two of you were at that time?

FLYNN: You know, after he had been in the shelter for first a few days, you know, he was only going to stay there for a few days by his accounts. A few days turned into, you know, a week. A week turned into a few weeks. And, you know, initially, you know, I think there was this thing like, this has to end.

At that point, I had begun to take my job - you know, I was a little older. I'd begun to take my job working with the homeless more seriously, and really had been trying to sort of get people off the street. Like, you know, not just sort of see this, you know, working in the shelter as sort of this wild, adrenaline, circus-like experience with - filled with, you know, crazy personalities that are entertaining - but actually like, OK, we could actually do something positive here.

And, you know, you take an individual, you figure out - it's like a case study, a caseworker, and you try to get him, you know, him or - I just worked with men there - you know, connect them to services, figure out what they need and connect them to service and get them back on their feet again.

But when my father showed up, it just sort of confused all that for me. Like I didn't want to give him special treatment, and yet he was getting special treatment because of who he was, because he demanded special treatment because of his oversized ego and because no one - you know, he was my father.

And so it felt like that he would take advantage of that, it felt like. It felt like he would sort of - you know, he would ask for the private room. He would - after he'd been there for a couple weeks, he went to my supervisor and applied for a job at the shelter. He thought that he would be a good, you know, a good worker at the shelter.

Which, you know, there was a rule about that. You had to be off the streets for a year before you could, you know, apply for a job. Which is a scene that we actually improvised with De Niro and Wes Studi. I don't believe it made it in the film, but it was sort of this wonderful improvisation where De Niro was, you know, approached Wes Studi, the supervisor, and asked him for a job. And presented his - you know, that he would probably be a better worker, even, than his son.

DAVIES: Now Nick Flynn, you of course eventually stopped drinking, became a successful poet. You wrote this memoir, which was successful. You have another one out. But I wonder, earlier on, did you think of writing in some way as scary, I mean, maybe connected to your father's, I don't know, failure and self-delusion?

FLYNN: Yeah, you know, writing for me was sort of the - you know, since I was a child, writing was sort of the worst life choice you could make. I mean, to be a writer in my family, my father had always identified himself as a writer to my mother when they met. He was writing this great novel, you know, before I was born. He was going to write this - he was writing this masterpiece, there was no doubt about it.

And so, you know, and part, part of why she left him was this delusional - this delusion of greatness and identifying it very directly with being an artist. I mean, you know, we did not - we were not a family of artists with my mother and brother and I. That was not sort of a viable life choice. We were sort of - you know, I became an electrician after high school.

And - but I always had this thing in me to write. But it was always sort of a little shameful, a little - it sort of meant you were, you know, like to say you were a poet was, sort of, saying you were kind of crazy. And I, sort of, carried that around for a long time. And I still kind of carry that a little bit, and I think it might be true, actually.

As a life choice, in this society, to say I am a poet is, you know, you might as well say you're Jesus Christ. It isn't exactly a respected life choice, always. But that said, you know, I think that's actually one of the reasons I continued with, because I was able to do it in private and, sort of, under the radar for many years. And feeling like I was maybe not doing, even the - you know, even today, it was a disreputable thing to do. To be a writer was disreputable in some way. And I think that actually was some kind of fuel for me to continue writing.

DAVIES: Writer Nick Flynn and director Paul Weitz collaborated on the film "Being Flynn" based on Flynn's memoir about his relationship with his father. They'll be back in the second half of the show. I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies filling in for Terry Gross who's off this week. We're speaking with AUTHOR Nick Flynn, whose 2004 memoir is the basis of the new film "Being Flynn," directed by our other guest, Paul Weitz. The film is based on Nick Flynn's experience in the 1980s when he was working in a Boston homeless shelter and his father Jonathan, an alcoholic and self-proclaimed great AUTHOR, came in looking for a room. In the film Robert De Niro plays Nick Flynn's father, Jonathan. Paul Dano plays Nick.

Nic, I want to come back to that time when you were working at the shelter and your father came in as a client. And this was a time when you weren't in the best place. I mean you were in your 20s. You know, your mom had committed suicide earlier. You were, you know, you were drinking, using drugs at times. And I wonder if when your father came into the shelter and - if that had a different impact on the way you saw people who use served. I mean I wondered if you didn't see yourself like those folks who were struggling, who were marginal, were on the street, but then when you saw your father in that position, did it, I don't know, connect you to your own problems in a different way?

FLYNN: When he showed up, I think eventually I think I could sort of see it as a portent of what could happen if I continued drinking and using drugs, and actually that I wasn't that far from the life that my father ended up living. But at the moment he came in, I think I had to, you know, shut down psychically and steel myself against this sort of this psychic devastation in some way, to see your father, you know, on the street. It's a very different thing to pick up someone you don't know from the street than to actually have other people pick your father up off the streets. It was, you know, psychically devastating.

And so I think I just sort of steeled myself to it and did not identify with it and say like, oh, this will be me. You know, if I had I think I probably would have quit drinking sooner, you know, rather than increasing my intake. That's sort of contradictory. It's a contradictory response to it, but that was my response.

DAVIES: You write that you could have offered him, you know, room at your place to stay overnight, tried to help him in a different way outside the shelter. Did you ever think of doing that?

FLYNN: Oh, I thought about it every day, every minute of every day. Sure. And then I ended up doing it sort of â what do they call it in therapy: transference. I ended up having some other homeless people stay with me. And basically everyone I was hanging out with at that time in the building I lived in it was, you know, extremely marginal. You know, we were not like - you know, the bar for our expectations in life was basically leg in the ground. And so, yeah. I mean I was surrounded by that and so I brought other people in, other homeless people in. My friends were basically very marginal. And I thought every minute of every day that I could open the door to my father and let him in. But then I also thought, what would that do to me if I brought him in? He was a very - a dangerous, to me, psychically dangerous character. I felt, I think, that he could destroy me if I let him in too closely at that moment. And maybe it's true.

DAVIES: And destroy you in what way? By placing demands on you?

FLYNN: Well, I mean...

DAVIES: Or what?

FLYNN: Oh, well, he was, you know, it was impossible to sort of - he was very slippery. I could understand, I couldn't understand him, like who he was. You know, I was probably terrified of being him. I didn't understand how he could, I was also, you know, considering myself a AUTHOR and here was a AUTHOR who was like calling himself a great AUTHOR who was now sleeping on the streets. So, you know, my sense of like what the future would hold for me was at risk.

And part of this is, one of the reasons that I felt that Paul Dano was like the perfect person to play me, which is a strange thing to say, I guess, but you know, one of the things is that he's the right age, I mean beyond being this sort of fantastic actor. When one's in their 20s, I think one does still feel - at least I did - that one could be destroyed by your parents. It sort of almost a mythic fear, archetypal fear. And it is possibly true in some circumstances. You know, I don't know if it's real for me. I don't know if my father actually would have destroyed me if I'd brought him in, but that was the feeling I had.

By the time I was in my mid-30s I actually could go to him and offer some help to him. But at that, you know, 10 years earlier, no, no.

DAVIES: Yeah. There's a moment in the memoir where you say, if I went to a drowning man, the drowning man would pull me under. I couldn't be his life raft.

FLYNN: Yeah. Sure. And you know, my mother had, you know, taken her own life just a few years earlier so, you know, there were sort of these two poles of - there was this grandiose like I will survive anything pole with my father. And then the, you know, the darkness my mother succumbed to - you know, I was navigating those two poles or trying to.

DAVIES: There seemed to be one difference between the film and the memoir, and maybe I'm not remembering this accurately, but in the film we see the father, Jonathan Flynn, challenging his son, Nick, saying things like: I made you. You are me. And this sort of graphic representation of what we see as Nick's fear that he can easily become his father. You know, a drunk, homeless, utterly dissolute. I don't remember that so much in the memoir and I was wondering, Paul, was that your way of capturing, yeah, that fear.

WEITZ: I took certain things from letters. I was able to read through a number of the letters that his dad had sent him, which obviously were some form of internal monologue expressed to the captive audience of his son. And it's interesting. You bring up this moment, which is one of the most dramatic moments in the film. Not necessarily the moment when the characters are expressing things the most directly, but where Jonathan says to Nick, I made you, you are me. Essentially taking full ownership over his personality and identity.

It was interesting to me that Nick said that when he showed his dad the trailer of the movie, that that was the part in the trailer that Jonathan Flynn particularly got a kick out of and he made Nick rewind it over and over again.

DAVIES: You know, another thing that's occurred to me, Nick Flynn, is that, you know, it was in the '80s when your father was in the homeless shelter. I mean you were different person then. You published the memoir 2004, 2005, I guess, and you've continued to grow and mature and think about these events. You've become a father yourself. And I wonder if when you look at your father now, is he a different guy than you saw in 2005?

FLYNN: Oh, yeah. Well, in 2005 or in 1987?

DAVIES: Well, in any of it. I mean as you process these events, is your understanding differently? I mean do you feel like if you were going to write that memoir now it would be a very different story?

FLYNN: I think I sort of captured him - I feel like that book did capture who he was. And, you know, I returned to him in the following memoir, "The Ticking Is the Bomb." I pick up his life, you know, after being homeless. So yeah, I mean I think he has, you know, he has continued to grow. He was a little bit frozen in time because of the alcohol. You know, he, you know, continued to drink. When he was off the streets he continued to drink daily. And only in the last like four years, since he's now been, now, you know, I had to sort of relocate him into a long-term care facility about four years ago, which is where, you know, Paul and Mr. De Niro and I went and visited him. And only since then he's not, he doesn't drink. He doesn't drink. He's not on any, he was on some anti-anxiety medicine initially, probably to get off the alcohol, and now he just is who he is, which is sort of an amazing thing. Now I actually get to see him, it seems like, as a, you know, a full, you know, human being, and he's still just as complicated, still just as strange, still just as filled with sort of these sort of platitudes, which seem, actually, in retrospect, kind of profound.

You know, one of the themes of the film that Paul picked up on was this thing he wrote me when I was, you know, when he was first in prison, that we were put on this Earth to help other people - which, you know, you can't really argue with. It's actually a beautiful sentiment. You know, it becomes sort of ironic and twisted when he shows up at the shelter and says, well, I'm the person you should help. But that's just sort of one of the layers of the film that we sort of tried to tease up.

DAVIES: Well, Paul Weitz, Nick Flynn, good luck with the film. Thank so much for spending some time with us.

WEITZ: Thanks for having us.

FLYNN: Yeah. Thanks so much, Dave.

DAVIES: Nick Flynn's memoir has been republished as "Being Flynn," which is also the title of the new film starring Robert De Niro, directed by our other guest, Paul Weitz. Flynn also has a new memoir called "The Ticking is the Bomb."

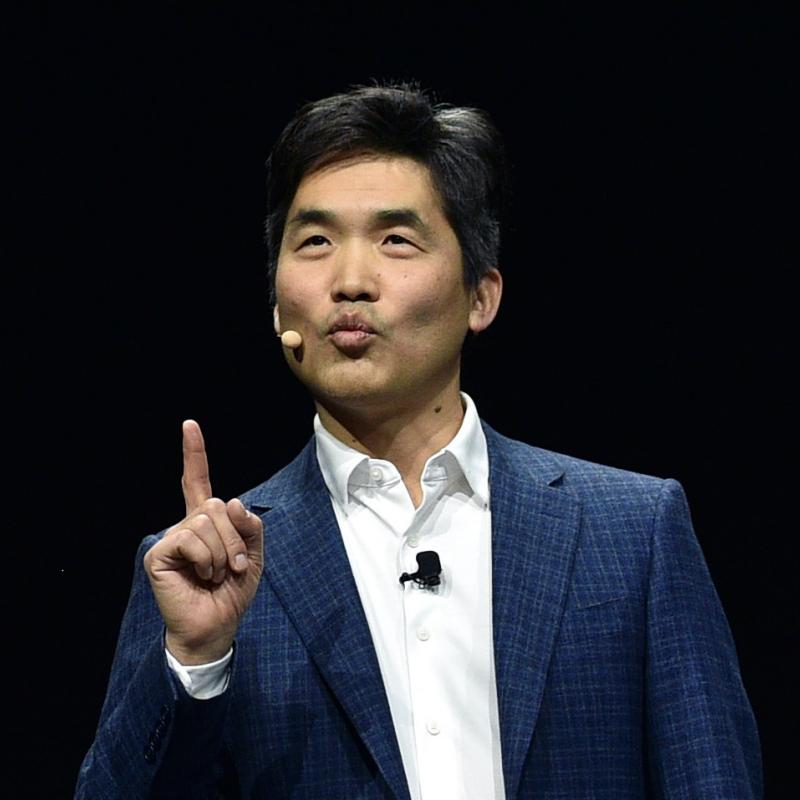

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: Scientists have known for a long time that different regions of the brain have different functions. Our guest, neuroscientist Sebastian Seung, says what really makes one brain different from another - why you have a special fondness for tacos while your spouse loves foreign films, or perhaps while some people become schizophrenics - has to do more with how our brains are wired than anything else.

The brain has billions of neurons, and Seung says the ways they are connected with one another make spying much about brain function and dysfunction. This wiring pattern, which Seung calls the connectome, changes constantly as we acquire new memories and experience emotions. It's dizzyingly complex, since every one of those billions of neurons may have a thousand connections. Sueng says everybody's wiring is different and it's at least theoretically possible to diagram it.

Sebastian Seung is a professor of computational neuroscience at MIT and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. His new book is called "Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are. "

Well, Sebastian Seung, welcome to FRESH AIR. One of the fascinating things that your book presents is the effort to actually map the neurons of the brain and their connections. I mean the human brain is enormously complex, a hundred billion neurons. But there is this case where scientists have managed to map the connectome, the connections of a very, very tiny worm. You want to just describe that effort?

SEBASTIAN SEUNG: Yes. So a connectome is a map of connections between neurons inside a nervous system. You can imagine it as being like the map that you see in the back pages of in-flight magazines. Imagine that every city in that map is replaced by a neuron, and every airline routes between two cities is replaced by a connection. There is only one organism for which the entire connectome has been mapped, and that's a tiny worm called Sea Elegance. It's just one millimeter long, and in the 1970s and '80s scientists mapped out all 7,000 connections between its 300 neurons.

DAVIES: So how did they do it?

SEUNG: You can take a worm and treat it like a tiny sausage and cut it into extremely thin slices using the world's sharpest knife, the diamond knife. These slices are a thousand times thinner than a hair. Now, take each one of these slices and put inside the most powerful microscope, the electron microscope, and image the nervous system of the worm at extremely high resolution. Once you're done, you have a whole stack of images of each of the slices. Effectively, it's a three-dimensional image. It's like a virtual worm. There's an image of every neuron inside this worm. Every synapse inside this worm has all been captured inside these images.

DAVIES: All right. So - so in contrast to this millimeter-long worm, I mean the human brain seems impossibly complex. I mean what are some of the challenges in trying to map the human connectome? Has it been tried? Can you do a piece of it?

SEUNG: Well, the simple answer is the progress in technology. First of all, the imaging of all those slices of brain can be automated now and made much more reliable. And the second point is that, remember that we have to analyze those images to find the neuron branches and the synapses.

There's no way that any person, any single person could look through all those images and do that task for a cubic millimeter of brain. There's so much data. But now we have computers that are getting better at seeing. It's true that robots don't see nearly as well in real life as they do in science fiction movies. But the capabilities are getting much better.

DAVIES: So 100 billion neurons in my head?

SEUNG: Yes. That's the estimate.

DAVIES: And we have each of these hundred billion neurons with thousands of connections to other neurons, is that right?

SEUNG: That's right.

DAVIES: All right. So let's take an idea, an image of a flower. Or one that you use in the book is a memory of a first kiss. How is that idea or that memory physically represented in the brain?

SEUNG: Right. Great question. People have wondered about that for millennia, at least. And we have tantalizing hints that we might be close to an answer to that question. So I will have to describe some of the theories and some of the evidence that we have so far.

Let's start out with your experience of the kiss first. Not the memory of the kids, but your actual experience. As I said before, that is represented in your brain as some kind of pattern of activity of your neurons. Neurons produce electrical pulses. Those are the signals that they use to pass information throughout the brain. And so let's imagine that some configuration of neurons, some constellation of activity is evoked by the experience of the kiss. And this might represent all kinds of information, not just the kiss itself but maybe the surroundings, the person that you're kissing and so on and so forth.

So somehow that experience has to become deeply imbedded in your brain in a manner that - well, I guess most of us never forget our first kiss. So it has to stay with you for a lifetime. And so the question is: How can an experience that is ephemeral become imbedded in your brain in a way that is almost permanent?

So the hypothesis has been that all those signals, all those transient signals, somehow modify the material structure of your brain as if - I guess the metaphor that Plato used was leaving an impression on a wax tablet. There's some kind of material thing that gets changed.

DAVIES: OK. So there is some assembly of connections that cement my memory of my first kiss, and part of it is the physical sensations, part of it is the moonlight shimmering off the water, part of it was what happened that day.

SEUNG: Why, you're very - this is a wonderfully romantic description. I guess you can remember your first kiss very well.

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

DAVIES: Well, I'm embellishing a little. But I guess what I'm asking is: Is there a neuron that associates with shimmering water, and another neuron with the color of her hair and another neuron that, you know, connects to another piece of it?

SEUNG: You're getting at the question of what is the representation of perceptions, which is - you have to address before memories. And yes, the evidence would be that maybe it's not a single neuron. It might be some population of a number of neurons, but they're activated by each of these properties. So any experience is somehow represented by this kind of combination of neurons, each of which is responding to some particular feature in the particular experience.

DAVIES: And the experience sort of established connections, which then remain, and so the brain is a little different than it was before the kiss.

SEUNG: Yes. And the crucial fact here is that neural activity can lead to changes in connections, that if two neurons are activated simultaneously or in quick succession, then the connections between them are modified. That's a crucial fact. There's empirical evidence for it. But the extension of that fact to an entire experience, as opposed to one connection between two neurons, that has not been adequately investigated.

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, we're speaking with Sebastian Seung. He's a neuroscientist at MIT. His latest book is called "Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are." Let's talk a little bit about how the brain develops. When a baby is born, the wiring, if you will, is not complete. What happens in those early months?

SEUNG: So the first thing that has to happen in brain development is happening in the womb. These 100 billion neurons have to be created, and then they have to migrate to their appropriate positions in a very complex dance. Then they're sending out their branches, and the branches are intertwining with each other. And finally, those branches are forming the synaptic connections with each other. And that extension of branches and a lot of the synapse formation is still happening after birth.

DAVIES: And how long does it go on? Do we know?

SEUNG: Well, as far as we know, this kind of creation of synapses is happening throughout your life. Part of the reason that we are lifelong learners, that no matter how old you get you can still learn something new, may be due to the fact that synapse creation and elimination are both continuing into adulthood.

In the 1960s, many neuroscientists thought that this process of creating and eliminating connections actually stopped by the time you were an adult. But now there's plenty of evidence that it keeps on going.

DAVIES: You know, there's some fascinating evidence that you describe, that the wiring of the brain in the first three years is critical. And there's this phrase: The first three years last forever. Can you give us some examples of behavioral observations that suggest that, in fact, things happen in those first three years which are critical, in some cases, can't be reversed?

SEUNG: One of the most outstanding examples is patients who are born blind because of cataracts. In poor countries, they can't get the simple cataract surgery that would restore their eyesight, and they grow up blind. If you give them cataract surgery when they're adults, it turns out that they still can't see. So this suggests that - and no matter how long they practice seeing, they can never really see.

They recover some visual function, but they are still blind by comparison to you and me. And one hypothesis is that the brain didn't wire up properly when they were little babies, and so by the time they become adults, there's no way for the brain to learn how to see properly.

DAVIES: Right. And it didn't wire up because it wasn't getting the proper feedback from the, I guess, the optic nerves?

SEUNG: That's right. So here, the assumption is that brain wiring is guided not only by genes, but also by experiences, that we need experiences for the brain to wire up and connect properly. When deprived of those crucial formative experiences, the brain doesn't develop properly. That's the best explanation we have at this point.

DAVIES: And explain the feral children and what they reveal, if anything, about this.

SEUNG: Sure. The feral children are the legendary cases of kids who were orphaned, abandoned in the wilderness and raised by animals. These kids, when discovered later on - let's say in adulthood - attempts were made to civilize them, but they never learned how to speak. They never learned normal social behaviors, never learned language.

And so, again, this suggests the existence of a so-called critical period, a period during which you have to have experiences for your brain to develop properly, and after which nothing can be done.

DAVIES: Does that make sense to you, that not being around other human beings who were speaking might've affected the brain connections in such a way so that it simply isn't possible?

SEUNG: Sure. It's entirely possible. These are not really science, because they're kind of anecdotal stories. They weren't studied carefully by scientists. But it's entirely possible. On the other hand, I wouldn't want to read too much into this. So sometimes, parents get scared when they hear stuff like this: the first three years last forever, if I screw up with my kids, my kids will be damaged for life, so on and so forth.

I think that proponents of this idea have gone too far in stressing the idea of irreversible damage. And you may be aware there's another kind of popular trend in neuroscience, which is to talk about neuro-plasticity, about the amazing power of the brain to recover in adulthood. And these are actually diametrically opposed takes on neuroscience. One stresses the inability of the adult ability to change, and the other stresses the amazing unlimited power of the adult brain to change. They can't both be correct.

DAVIES: Well, where are you on this?

SEUNG: Well, the truth, of course, has to be somewhere in-between. That's a boring kind of answer. But with science, we want to rigorously investigate what kinds of changes specifically are possible in adults. And the next point I would say is that we shouldn't regard these as fundamental limits. They're not like the laws of physics. These questions have changed really dependant on the conditions.

There may be new learning methods that enable adults to change when they couldn't change before and, more futuristically speaking, there could be new drugs, new neuro-technologies that will enhance the brain's capability for change.

DAVIES: Sebastian Seung's book is called "Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, we're speaking with neuroscientist Sebastian Seung. His new book is called "Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are." I mean, one of the interesting ideas that you mentioned in the book is the notion that when a baby is born, there are certain functions that, if they don't develop in the first three years, might never come, because they were really critical to our ancestors being able to function, I mean, you know, their capacity to interpret visual signals or auditory signals, whereas a cultural kind of enrichment, you know, from reading is not something that maybe our prehistoric ancestors needed and therefore is not quite so critical in the early wiring of the brain.

SEUNG: Yes. Again, that's a cautionary note. The examples we know of irreversible damage to the brain because of deprivation all have been associated with severe deprivation, severely abnormal deprivation. For example, being deprived of sight by cataracts is an abnormal kind of deprivation. Or never being exposed to language, that is very strange and abnormal, almost never happens.

So you shouldn't jump to the conclusion that depriving your kid of the chance to hear Mozart is going to damage them irreversibly. That seems like a big stretch.

DAVIES: So if we were able to map the neural connections in the brain, what are some of the implications, say, for treating neural disorders?

SEUNG: Since an entire human connectome is far away, I'd like to emphasize that even doing small parts of the brain now is going to tell us a lot about brain function. So one kind of study we would like to do is to search for these connect-topathies(ph), these abnormal patterns of connection that are hypothesized to underlie mental disorders like autism and schizophrenia.

We can do this by taking a little piece of brain and seeing whether the neurons inside that piece are connected in a way that's different from a piece of normal brain. Now, how would you do this kind of experiment? I should emphasize that this chopping up of brains and so on is a procedure that's done on dead brains. It can't be done on live brains.

So we can do these kinds of experiments on animals, because scientists are creating animal models of mental disorders. They take the genetic abnormalities that are associated with autism and schizophrenia, and they put those genetic abnormalities in mice. And it turns out that sometimes, these mice have abnormal behaviors, indicating that they have something analogous to the human mental disorder.

The next obvious question is: What's different about the mouse brain? And we can address that by finding a connectome of a particular part of the brain that is involved in these abnormal behaviors. Now, what about human brains? Well, you can imagine doing experiments on pieces of brain that are removed during neurosurgical procedures - for example, epilepsy. Neurosurgeons sometimes remove pieces of epileptic brain tissue, and the obvious question is: What's different about that piece of brain tissue that leads that tissue to generate epileptic seizures? We could address that through connectomics.

DAVIES: So it might be at least theoretically possible, in decades, to treat an abnormal connection in some way?

SEUNG: Well, I don't want to promise too much. My goal is simply to see what's wrong. That's not, in itself, a cure, but obviously it's a step towards finding better treatments. The analogy I make is the study of infectious diseases before the microscope. Imagine what that was like. You could see the symptoms, but you couldn't see the microbes, the bacteria that caused disease.

We're in an analogous stage with mental disorders. We see the symptoms. Most of these disorders are defined only by their symptoms. But we don't have a clear thing that we can look at in the brain and say: This is what's wrong.

DAVIES: Well, Sebastian Seung, it's been really interesting. Thanks so much for speaking with us.

SEUNG: Thanks a lot, Dave. I really enjoyed it.

DAVIES: Sebastian Seung's new book is called "Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are."

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.