Other segments from the episode on October 3, 2008

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20081003

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Music On The Mind: Oliver Sacks' 'Musicophilia'

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

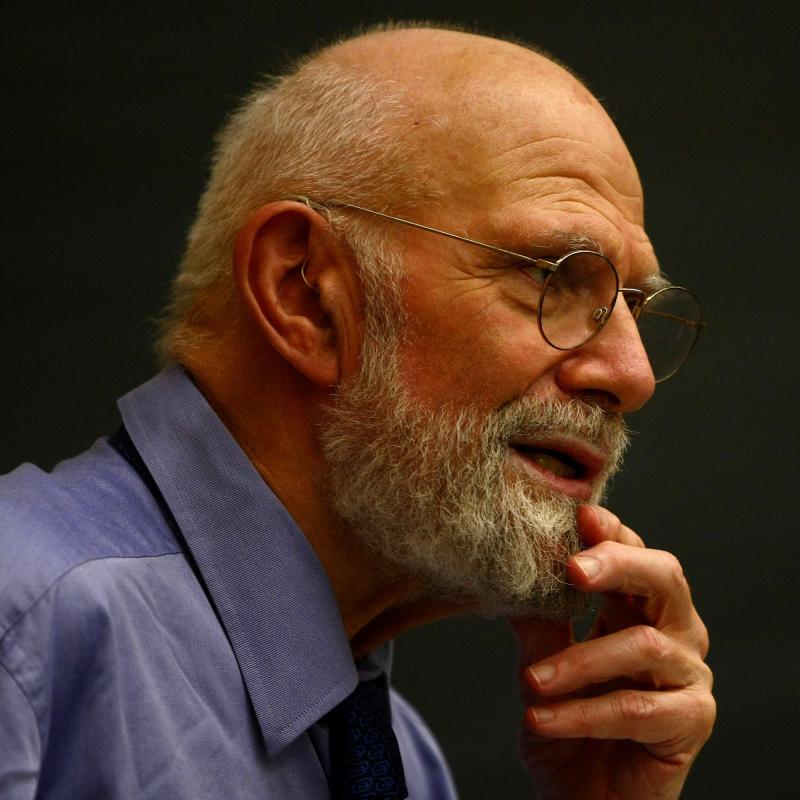

This is Fresh Air. I'm David Bianculli, TV critic for Broadcasting and Cable Magazine and tvworthwatching.com, sitting in for Terry Gross. Our first guest today is one of the world's best known neurologists, Dr. Oliver Sacks.

He's famous for his books chronicling case studies of patients with neurological disorders that have produced strange distortions of reality. One now famous example is the title story of his book, "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat." In his book, "Awakenings," which was made into a movie, he told the stories of patients awakened by medication after years of being institutionalized with a Parkinsonian sleeping sickness. Through such stories, Sacks offers insights into the brain and our experiences of reality.

His latest book updated with new information and now out in paperback is called "Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain." It's about the profound affect that music has on us and tells the stories of people whose neurological disorders have altered their perceptions of music and their musical abilities. These case studies pose larger questions such as why do some people have perfect pitch while others can't carry a tune? Terry spoke with Olivier Sacks last year, when "Musicophilia" was first published.

TERRY GROSS: Olivier Sacks, welcome back to Fresh Air. You have told many amazing stories in the book. The book opens with one of those stories of a 42-year-old orthopedic surgeon who is using a pay phone in a phone booth during a lightning storm, and his head was struck by lightning through the phone. What change did it produce in him musically?

Dr. OLIVER SACKS (Neurologist, Author): He was hurled backwards, and he was, in effect, killed for a short time. He had a cardiac arrest for maybe 30 seconds, and, of course, his brain got no oxygen during that time. And he had some immediate consequences, loss of memory and so forth.

This came back, but then he developed a sudden insatiable passion, as he put it, for hearing piano music and then for playing piano music, despite the fact that he'd been really without any particular musical taste or talent all his life. Then he started to have dreams that he was composing music, and when he woke, the music was still going through his head, and so then he wanted to be a composer as well as a performer.

And all of this happened, really, in the course of two or three days in which he was completely transformed. He continued to work as a surgeon, but he started getting up at three in the morning. He got himself a piano teacher. He learned to transcribe the music which was going through his mind. But this change has been permanent, and in 15 years now, he has become quite an accomplished musician in a way which could never have been predicted before.

GROSS: What does that story tell you about what happens neurologically with music? What do you take away from that story?

Dr. SACKS: Well, I don't know exactly what has happened with him, and I hope we can sort of get some brain imaging, a functional brain imaging, and see what has happened. This sort of imaging was not available really in the early 90s, when he was struck by lightning. But there are a number of situations in which maybe a rather sudden astonishing release or emergence of heightening of musical abilities - one sometimes sees this with epilepsy, with temporal lobe epilepsy, one sometimes sees it with a rare disease called frontotemporal degeneration, when the temporal lobes get released, and music and visual patterns can play in the mind. I suspect that something like that happened with the surgeon.

GROSS: You mentioned epilepsy. You worked in an epilepsy clinic for a while, so you're exposed to a lot of people with epilepsy, and you write about how some people with seizures would hear like beautiful music, but other people would be tormented by music. The music would be horrible for them.

Dr. SACKS: Well, occasionally, music can cause a seizure. I saw a patient, I'll describe her, who told me that she had been found unconscious with a bitten tongue next to the radio three or four years ago. And all she could say was that she had heard some Neapolitan songs being played on the radio, songs which she normally loved, but these produced a queer feeling, a strange faint feeling, and then she couldn't remember anymore. And this was regarded as an unhelpful piece of history, but then she had another seizure, another convulsion, also following a Neapolitan song, and it became apparent that Neapolitan songs would give her seizures and no other music.

She came from a large Sicilian family, and Sicilian and Neapolitan music was always being played. If it was played a wedding, she had about 20 seconds to block her ears and get out of ear shot. Otherwise, she would be taken over. And she was sort of heartbroken because this was music she loved, and now, she started to dread it.

GROSS: Which part of the brain deals with music?

Dr. SACKS: Well, a great many different parts of the brain deal with the music, but the auditory parts of the brain obviously deal with music in the first place with a sound of music. Then there is analysis of the pitch and the rhythm and the tempo and the melody, melodic contours and other aspects of music in different parts of the brain. The motion of music, the tempo, and the rhythm is separately registered and so also is the emotional reaction to music. So there are really 20 or 30 different parts of the brain which are being recruited in the musical experience. And these are never quite the same in any two people.

GROSS: Is language as complex as that? Does it call on as many parts of the brain as music does?

Dr. SACKS: Language doesn't seem to call on as many parts of the brain, and this may be a reason why, if one has a stroke or something and loses language and knocks out a particular language area in the left hemisphere, one usually retains one's musical sensibility, and one can still recognize and sometimes sing songs.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is the neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks, and his new book is called "Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain." What have MRIs allowed researchers to see about the differences between musicians and non-musicians in the brain?

Dr. SACKS: Well, there have been very very striking findings here. You know, people have been looking for some sort of cerebral correlate of intelligence or of musicality or artistic gifts or literary gifts for ages. When Einstein died, his brain, in fact, was stolen by the pathologist and subsequently cut into little bits and distributed. People wanted to find out what was Einstein's secret. And nothing clear cut really came of this. And in general, if you look at a brain, either in life with an MRI or later, you can't tell whether it's the brain of a genius or fool, whether it's the brain of a visual artist or a literary artist.

But you can look at a brain and say that's probably the brain of a musician because musical training and involvement of music enlarges various parts of the brain, the corpus callosum, the great band which goes between the two cerebral hemispheres, parts of the auditory cortex, parts of the cerebellum, parts of the frontal lobe cortex. There are striking changes which can occur within a year or within a single year of musical training. And these are changes which are really visible to the naked eye, at least if one knows where to look. So the power of music to alter the brain is very very striking.

GROSS: Is this is a chicken-and-egg thing? Is there a person with a certain kind of brain and certain enlarged parts within the brain that becomes a musician, or is it that musical training that has the impact on the brain?

Dr. SACKS: Well, we don't fully know because usually, one does not do an MRI on a three-year-old or a four-year-old, a gifted three or four-year-old, before they start musical training. I think we need to do this, but what we do know is that the musical training itself can make very great changes as - though, obviously, some people are born with greater musicality and others not. Usually, innately musical people get early and intense musical training.

GROSS: Have you ever looked at an MRI of your brain and, like, analyzed your brain?

Dr. SACKS: Yes, actually quite recently - both the structural MRI, which, to my relief, did not show Alzheimer's or anything like that.

GROSS: So what did you learn from your own MRIs about your brain?

Dr. SACKS: Basically, it seems similar to other people's brains.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Dr. SACKS: Although, having said that...

GROSS: Uh huh.

Dr. SACKS: You know, as one examines this in more detail, you do, in fact, find that MRIs, and especially functional MRIs, are as individual as fingerprints, and this is especially so with musical responses. No two people are exactly the same, and sometimes, you know, an individual's functional MRI with music may change over the years as they change, as perhaps, you know, as you described earlier, when perhaps, say, a tune which didn't move you much, heard years later is strangely familiar and gets you, something must have happened. And I think that, you know, that could probably be showing up if one had an MRI of the earlier hearing and then the functional one of a later hearing.

GROSS: You know, you described somebody who has perfect pitch in your book, and who wonders why is it that people are mystified at perfect pitch. Yet everybody seems to be able to describe a name - to see and name colors. Now, to me, being able to identify a G or, you know, a G above C or an A sharp or something is completely different than being able to say that's turquoise.

Dr. SACKS: I take it that you don't have absolute pitch then.

GROSS: I sure don't.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Dr. SACKS: Well, nor do I. It's - but to people who do have it, it seems to be as natural to say G sharp as to say turquoise. And they don't have to make any explicit comparison with, you know, with any other pitch, just as we can say something is turquoise without having to compare it to pink or green.

There's some suggestion that all of us may have absolute or perfect pitch in the first year of life, but then the vast majority of us then lose it. Although with intensive musical training, it's more apt to be retained, so absolute pitch may occur in something like one in 10,000 people in the general population, but it's closer to one in 10 or one in 15 with professional musicians.

GROSS: But do you think it's - notes like G and A and B flat, they're just kind of like human constructs, like they don't exist. That scale doesn't exist in nature. It was created by humans, so...

Dr. SACKS: Well, I mean, I suppose one might say that blue and green don't exist in nature. I mean, they're obviously - there is a continuous spectrum of wave links, but we arbitrarily pick out a certain segment to that and say, we'll call this blue, or we'll call this green. And similarly, I think out of a tonal continuum, we will pick out a particular thing, and, you know, we will divide an octave. An octave is a universal - is a mathematical universal and is a physiological universal. Middle C has double the frequency of the C below it, half the frequency of the C above it. And if a human being can tell an octave, and if we then divide an octave arbitrarily into, say, 18 steps or whatever, then we get our particular scale. The Hindu scale is different. I mean, obviously, culture comes into it, but there is something natural, as well.

GROSS: You know, one thing I often wonder is why are familiar melodies so special to us? You know, like you can go to a concert and really like the new songs a performer does, but when the performer does the song that you already know and like, the familiar song, there's just a different feeling that overcomes you. And I have found that even songs I might not have liked in their own time, when I hear them now, this isn't always true. But it's sometimes true that the familiarity of it kind of overtakes me. Do you wonder, like, what causes that? Why is there, like, a special groove in your brain that seems to resonate with familiar melodies?

Dr. SACKS: Yeah. Well, I mean, familiarity always goes, I think, for the feeling of a particular memory, a particular place, a particular mood, a particular emotion, and there's a very, very intense relationship between music and memory and emotion. I think music has a tremendous mnemonic power, which, of course, Proust writes about. I think nothing, you know, it's almost as powerful as taste or smell. Music brings back things, but as you say, familiarity alone can do it and can sort of give one goose bumps, bring back one's early years.

GROSS: You write not only about music that we hear, but you write about music hallucinations, music that only exist in our minds, and you said that you became interested in musical hallucinations when your mother at the age of 75 started hearing patriotic songs from the Boer War playing incessantly in her mind. First, you should tell us what the Boar War was and why your mother would know those songs?

Dr. SACKS: OK. Well, my mother herself was surprised because she was only seven at that time, and the Boer War was going in South Africa. And in general, a seven-year-old child is not that interested in a remote war. But there were lots of patriotic songs that were being sung in England at the time.

But my mother was intensely surprised. She said that she, you know, she thought these songs had never meant anything much to her in the first place. And secondly, she hadn't given them a thought, a conscious thought, in nearly 70 years. And now, suddenly, they were erupting inside her. She knew that it was going on in her head. She didn't feel that, you know, the songs were actually being played, and so she wondered what had happened. She herself had been trained in neurology. She wondered if she'd had a little stroke. She wondered if it was the medications she was taking for high blood pressure. Whatever it was, it's sort of - the songs died down in a week or so, and they never recurred. And it was just a strange little episode.

GROSS: What do you make of it?

Dr. SACKS: Well, I was intrigued and also slightly frightened by this. I mean, I'm now in my 75th year, and it doesn't seem that old. But, you know, but at the time, I thought of my mother as very old, and I wondered whether, you know, in my end is my beginning, whether the mind was somehow preparing to go, preparing to depart, and regurgitating very early memories.

But I was also very much reminded of something which I had read a few years earlier when the - about people with temporal lobe epilepsy who would sometimes suddenly have songs come into their head and has been found that particular part of the brain responded to that. Although that was different, because they would have, as it were, a seizure with a song going through their head for two minutes and maybe some twitching movements, maybe unconsciousness where, as what my mother described, was a sort of a kaleidoscope of songs going on continuously for hours on end.

And I didn't know what to make of it, but I was intrigued. And later, in the 1970s, I was to encounter this in several of my patients, most of whom were rather deaf, although at that time, I noted that they were deaf without making any explicit connection between the auditory hallucinations and the deafness.

And in some of these cases, people were really very uncertain as to what was going on. One old lady was woken in the middle of the night by hearing Irish songs played tremendously loudly. You know, a hallucination is quite unlike imagery. You feel a musical imagery as your own. You think of a song where the hallucination startles you. You look around. You wonder what's going on. Has someone turned on the radio? Was there a band outside?

And this woman wondered why music was playing loudly in the middle of the night in a nursing home. She wandered out. She was amazed that everyone else was asleep. She thought they'd all been sedated. She couldn't find a radio. She wondered whether a filling in her tooth was acting as a crystal radio, as a transistor. And then finally, she had to infer that something was occurring in her brain, what she called a radio in her brain, which was behaving autonomously and convulsively.

This could be very frightening to people. They - you know, one associates hearing things, people wonder, are they going mad? You know, is their brain rotting? And, in fact, there's been a great underreporting of musical hallucinations. I think, it looks - people are afraid to mention them.

GROSS: Well, as I say, I hear much more about visual hallucinations than auditory ones, though, you know, people who hear voices...

Dr. SACKS: Yeah.

GROSS: Have auditory hallucinations, but I guess that's different from music hallucinations.

Dr. SACKS: Yeah. It's completely different because, you know, the voices are accusing, persecuting, humiliating, seductive, whatever. The voices seem to be addressed to one. They seem to be moral agencies. They make one acutely uncomfortable, and none of this is the case with a musical hallucination, which is like a sort of automatic replay of music one has heard in early life, which may not mean anything in particular to one.

Typically, people with musical hallucinations never get voice hallucinations. And one of the first things, you know, if people have these, is to, you know, is to listen carefully to their story and reassure them that this is not psychotic, that it's completely different from a psychotic hallucination.

GROSS: Dr. Sacks, it's been great to talk with you again. Thank you so much.

Dr. SACKS: Lovely talking with you, Terry.

BIANCULLI: Oliver Sacks speaking to Terry Gross in 2007. His latest book "Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain" is now available and updated in paperback.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

95336672

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20081003

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

J.L. Chestnut, Campaigning For Rights In Selma

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is Fresh Air. I'm David Bianculli in for Terry Gross. Pioneering Civil Rights activist, Attorney J.L. Chestnut, died earlier this week of kidney failure, the result of an infection following surgery. He was 77. J.L. Chestnut was a significant figure in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1958, he became the first black lawyer in Selma, Alabama and stayed in the South to fight injustice and represent needy clients. He represented Martin Luther King, Jr. and other Civil Rights activists when they needed help in Alabama. And he was part of the pivotal protest in March 1965, when men and women gathered to march from Selma to Birmingham to demand voting rights. The marchers were attacked by state troopers and white posies on a day now remembered as Bloody Sunday.

The Voting Rights Act was passed in part as a result of that protest, and J.L. Chestnut was there working with the NAACP. He fought for equality ever since and turned his Selma legal practice into the largest black law firm in Alabama. Terry spoke with J.L. Chestnut in 1990, when he and Julia Cass, a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, had collaborated on his memoirs, "Black in Selma." In his book, Chestnut writes about growing up in Selma in the years before the Civil Rights Act. To help him get ahead in the world, his mother had him use a cream to lighten his skin.

Atty. J.L. CHESTNUT (Civil Rights Lawyer): I never agreed with that. I want along - my mother is a very strong woman, and she felt that black people couldn't help anybody. They needed all the help they could get in Selma or in the South when I was growing up in 40s. And so she cultivated white people, and she noticed and told me that, if you look about you, all of the prominent black people are light skinned, the postman, the doctor, the better known preachers, those who pass at the larger churches, and so she would use this skin lightening to help her only child get ahead. That is the way she saw things. I never really believed in it, but she's such a strong woman, you go along with it.

GROSS: What was in the cream by the way, do you know?

Atty. CHESTNUT: I don't know, but it worked because I'm brown, and I turned kind of reddish to her absolute delight.

GROSS: So it really changed the color of your skin?

Atty. CHESTNUT: It really did.

GROSS: Huh. Do you regret that?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, I think it makes you think about a nation that would cause people to develop so much self-hatred that you could really have a product on the market commercially successful to try and change one's appearance. And then I'm really sad that my mother would have to stoop to that to try to, in her view, to get her son ahead in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

GROSS: You went to law school at Howard University, and then you returned to Selma, Alabama. Why did you go back home?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, Martin Luther King, Jr., who's one year older than I am, had, with Rosa Parks, started virtually a revolution in Montgomery, which is just 50 miles east of Selma. And other things were developing in Selma and in the South which indicated to me that the action likely to come would come in the South rather than in Harlem or in the north.

Now, I did not anticipate any action on the scale as a Civil Rights Movement. We had some very modest goals in mind. If you remember the Montgomery bus boycott, Martin and the group were not asking for integrated buses. They were just asking for the right to sit from the back up half way and have white sit from the front half way. They were not even seeking integration of the buses because that was almost fantasy land back then. So I didn't anticipate anything like what did happen.

GROSS: When you returned to Selma as a lawyer, what kind of cases did you get, being the first black lawyer in Selma?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Yeah, let me give you some flavor of what was going on there. There were only 150 blacks registered to vote out of a pool of about 15,000. Not one black, not one in the entire state of Alabama, had ever served on a jury, no blacks had jobs downtown except as delivery people or janitors, and a black person could literally lose his or her life for not yielding a sidewalk or saying sir or ma'am to white person.

Fear was everywhere. It engulfed Selma, and it engulfed the South. Now, that is the Selma, the South that I went back to to practice law. And the white lawyers there were not only the rulers of the town, they were the country club sophisticates and all of that. They didn't associate with ordinary white people, and they certainly didn't want any part of some black coming in talking about he was a lawyer in the Dallas County Bar Association.

Selma is a county seat of Dallas, promptly passed a resolution and took it to each bank and asked the banks not to lend me any money so that I could open an office. And I had no intentions of trying to borrow any money in any event because I didn't have any collateral. But everybody was hostile, the judge, the officers of the court, the jury because these seemed to be the same white males all serving in every case. And I had to ask myself many, many times whether or not my client really would be better off with a white lawyer, one who didn't know anything, didn't know as much as I did.

GROSS: You make an interesting point in your book. You said that we know, when you started as a lawyer, there was no Voting Rights Act, there was no Civil Rights Act, so a lot of injustices couldn't be taken to court.

Atty. CHESTNUT: What we hoped to do was to make new law. We didn't expect to win at that level. The NAACP at that point were financing a lot of criminal cases which were pregnant with the possibility of establishing some of the laws we have on the books now, the Miranda thing, where the police had to read to you your rights and all of that.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Atty. CHESTNUT: And the South was fertile territory for that because just being black in the South made one vulnerable to the police and all of their excesses, and many of them were untrained in their relationships with blacks, unrestrained. So we were trying to get cases to the United States Supreme Court that would deal with the vol - whether confession was voluntary. Eventually, we did and changed the law in that subject. A lot of things which are now the law came about through some of our efforts and the court, just with the passage of time, got where we were trying to push them way back in, you know, 1958, 1960.

GROSS: What was your reaction as a, quote, "local" when Martin Luther King came to organize in Selma in 1965?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, I had been somewhat ambivalent about all of the Civil Rights leaders there. I felt that what they were saying was directed more at the masses than at me. After all, I had two degrees, too, and I was educated, and Martin had views which ran counter to everything I'd learned in law school. For an example, he insisted that he had a high moral right to disobey an unjust law, and he would make the determination when the law was unjust. That is not what I learned in law school. That was not what I believed in. I felt that you go to court to get a law declared unconstitutional. I wasn't quite sure about all this unjust businesses. That's not the terminology that lawyers used.

In addition to that, Martin was always trying to get me to give up my weapon and calling me a man of little faith. And I was telling him that, you go ahead and preach to the masses, but I'm not paying you any attention. I'm going to keep my weapon because it can bark here and bite way down the street, and Martin would laugh.

But I knew that his presence in Selma meant that more people like my mother, middle class blacks, would become involved, that Martin's presence gave a legitimacy to the movement that it otherwise would not have. Also, as long as he was involved, important and powerful white people in Washington would be watching. So he meant everything to the movement.

GROSS: Did you ever get more comfortable with civil disobedience as a tactic for Civil Rights?

Atty. CHESTNUT: I was finally convinced that Martin was correct, and the people who were paying me were incorrect. It is not generally known, but you take Bloody Sunday. That started out of a situation where a young man, Jimmie Lee Jackson, was shot dead by the state trooper. People were so frustrated and all that. They came out with a grotesque idea of just taking Jimmie's body and marching 50 miles to Montgomery and putting the body on George Wallace's desk.

And, of course, that was not done, but it was agreed to make the march to Montgomery. And Martin was not involved in the first march. But he came on, I think, the day following. And then Martin - what is not generally known is, while they were putting the people in the streets, they were not paying for that. The NAACP Legal Defense fund in New York was financing that.

And they were a legalistic organization. That's who I worked for. Their view was that you take two or three obviously qualified people, send them down to get registered, and when they are turned down, you go into court. You've got a perfect case. Martin was repudiating all that by sending 500 people down. Because he said he wanted to win in the court of public opinion. He was not interested just in adding a few more voters to the voters' voting roles in Selma. So I eventually came around to the point of view that he was correct and my bosses were not.

GROSS: Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965. It happened during a march from Selma to Montgomery to petition George Wallace for the right to vote. The march was broken up violently by state troopers. Would you share some of your memories of that day?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, I had come over from Mississippi. I had gone across the river early, across the bridge, because they would not let lawyers march. You know, you had enough foot soldiers. What we didn't have were enough lawyers. It didn't make sense to have lawyers in jail. So I had gone across the river early and not knowing whether there would be a march. And I get to a telephone because once a march started, you have the FBI, the press, and everybody fighting over the one telephone. So I went over early to tie it up in case there would be a march. And I'd have to describe to the NAACP what was happening because they were paying the bill.

And I was over there tying up the telephone, and I looked up, up toward the bridge, and there was John Lewis, who is now Congressman John Lewis from Georgia, Atlanta, and this group of marchers coming toward this great line of state troopers and possies. And I began to describe the scene over the telephone to New York, and then John and the group came face-to-face with the troopers, and I heard some voice, a state trooper, who said, stop; this will be as far as you will be permitted to go. Turn around and go back to your churches.

And then John and the others began to kneel and pray. And then I heard something that sounded like a tear gas canister hit the pavement. And then there was smoke, bedlam, confusion, blood, tears, cries, and there were these big hefty posse men swinging billy clubs the size of baseball bats and coming down across the heads of women and children. My eyes were hurting. My head was hurting, and New York was screaming over the telephone, what's going on? What's going on? And I tried to pull some women back out of the street, and it was just awful.

It was one of the lowest days of my life. At that day, I lost all faith in America. I lost all faith in white people. I said, my God, black people will never be citizens. We will never be what we ought to be in this land. And what is this? I have gone to Howard University. I'm a lawyer and an officer in the white man's court, and here these people are trampling on my folk in the streets, blood everywhere. And they are trampling on the Constitution, and nobody does anything about it because these people are black, and I was just almost in tears.

And two days later, I had to revise and make a new assessment because white people and black people came from all over this nation. They'd watched it on television, and they were thoroughly upset at what they saw. You know, it's easy to send a check down from New York and say I'm with you. It's something altogether different to come down and lock hands with a black person and say I'm ready to go to jail, I'm ready to die if necessary. And I saw hundreds and hundreds of people come from all over this land to join with us in this little town of Montgomery, and I had to look and reassess all over again. And my faith in this nation, my faith in the human race was restored.

GROSS: I'd like to get back now to something you said earlier when we're talking about Martin Luther King. You said that one of the things he wanted you to do is to give up your weapon, and that you're unwilling to do that. It was a gun.

Atty. CHESTNUT: That's right.

GROSS: You write that you actually gave up your gun the night Martin Luther King was assassinated.

Atty. CHESTNUT: I did. I threw it in the river.

GROSS: But why?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, that was my deep feeling over Martin. I stayed down there on that river, under the same bridge, the Edmund Pettus Bridge, crying for about 30 minutes and reflected on it that my kind of weapon certainly had not saved Martin. It didn't save Jimmie Lee Jackson. I couldn't think of anything it had done for me, really. And I'd seen John Lewis stare down a whole regiment of state troopers and sheriffs, and he had no weapon. And the things that had been brought about, the changes that had occurred in Selma and in the South, had not come at the end of any gun. So as a tribute to my friend who had given his life in Memphis, I threw it away and watched it sink in the river, and I felt better.

GROSS: Had you ever used it? What did you want it to do for you when you had the gun?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Oh, just for self protection. I was not going to attack anybody. But if they came to get me, I would be ready. You know, Martin Luther King was preoccupied with death, foreboding all the time. And he said more than once that they are going to come for us, each one of us, and we won't be back, and I believed him. The only difference is I had a weapon, and I had intended to take some with me.

GROSS: When the Voting Rights Act was actually passed, what were the immediate effects in Selma?

Atty. CHESTNUT: The immediate effect was that within six weeks - in a six-week span, we went from about 200 registered voters to 9,000. People who could not vote, had no voice in their government, in a matter of six weeks became very important players.

But we saw immediate impact of that in the court room. Blacks began to show up on juries. White politicians had to temper what they said about blacks, and some blacks began to feel that they could run for office. Where there had been hopelessness, we now had hope. Where we felt - I certainly felt that all we could really hope for was to make some adjustments around the edges in the economic sphere or maybe get enough votes to keep - to getting the white policemen out of black Selma. I saw now that we could do much more than that, that blacks could really sit on governments and pass laws that affected both black and white people. America began to develop some meaning for me.

GROSS: Now that your memoir's complete, your autobiography, and you can see your life compressed between the covers of a book, has it led you to think about anything that you haven't thought about before or see your life in a different context than you'd seen it before?

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, when you are battling and going from one war to the next, so to speak, you really don't have any sense of the whole, and this book has caused me to see the many, many barriers that have fallen in the last 30 years that I had never really given any thought to.

I am really astounded at the progress we had made, but I'm even more astounded at the progress we haven't made. It's like talking to the white people in Selma, who were always telling me, said, look how far you've come in no time at all. And I will always say, that's true, but look how far we have to go. But I've had a chance to view for the first time because of this book. I have had the chance to look back over 30 years. And I'm not displeased with what I see.

GROSS: I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

Atty. CHESTNUT: Well, I'm glad to be here.

BIANCULLI: J.L. Chestnut speaking to Terry Gross in 1990. The Civil Rights activist and attorney, who was the first black lawyer in Selma, Alabama, died this week at age 77.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

95338969

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20081003

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-1:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

'Rachel Getting Married': Demme's Masterpiece

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

In the past decade, director Jonathan Demme, who won an Oscar for "The Silence of the Lambs," has concentrated on documentaries and concert films. His newest movie is a fictional film made with documentary techniques, featuring a hand-held camera and improvisation with a large ensemble. "Rachel Getting Married" stars Anne Hathaway and opens this week in limited release. Film critic David Edelstein has this review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN: In "Rachel Getting Married," Kym, played by Anne Hathaway, returns to her family's Connecticut house for her sister Rachel's wedding after nine months in rehab and promptly makes herself the center of attention. At the rehearsal dinner, she rises to toast to her sister, and we know from her first wayward sentences she's going to make a fool of herself. It's a familiar setup in movies and on TV these days, the exhibitionist opens his or her mouth, embarrassing confessions leap out, and the camera takes in the wreckage while we squirm or snicker or both. That's what happened in another recent marriage movie, Noah Baumbach's "Margot at the Wedding," in which nearly every encounter was engineered to make us cringe at the character's monstrous egotism.

But in this film, something unusual happens. As Kym babbles away about her 12-step program, we start to feel emotions other than discomfort. For director Jonathan Demme and first time screenwriter Jenny Lumet, Kym's humiliation isn't an end in itself. We go through it with her and come out the other side and feel for this unstable child-woman who longs to make things right but never can. There's a sense of loss in every frame of "Rachel Getting Married." It comes from a past family tragedy that's only gradually revealed.

But countering that is the movie's overflowing energy and bustle and all the wonderful performers acting their hearts out. Among them is Hathaway, who's amazingly vivid. A former teen TV star, she has a habit of telegraphing her character's emotions. But this time, her mannerisms fit. Kym was a teen model, too, and it makes sense she'd draw attention to herself by pulling faces. And what a face Hathaway has to pull - the dark eyes, the heavy mouth, the teeth like bowling pins. Kym's mood swings prompt her anxious father, played by the superb Bill Irwin, to rush in and coddle her. She's impossible to ignore. Rachel is played by Rosemarie DeWitt in her first big movie role. And although she doesn't resemble Hathaway, she meshes with her. Rachel is at long last fed up with being upstaged, and when she stands up to her sister, we like her better.

(Soundbite of movie "Rachel Getting Married")

Ms. ROSEMARIE DEWITT: (As Rachel) She's forgotten she even referenced the boundaries that even though I actually know what I'm talking about.

Ms. ANNE HATHAWAY: (As Kym) By the way, I'm not in crisis. I haven't been in crisis in a year.

Ms. DEWITT: (As Rachel) You just got out of rehab.

Ms. HATHAWAY: (As Kym) My God, why is this so difficult for you to understand? Rehabilitation. Crisis. You should really learn the difference. No, it's like - it's like you're not happy unless I'm in some kind of a desperate situation. You had no idea what to do with me unless I'm in crisis.

Ms. DEWITT: (As Rachel) You know, you are so much more involved in your suffering.

Ms. HATHAWAY: (As Kym) I'm not - who is talking about that?

Ms. DEWITT: (As Rachel) Your suffering is not the most important thing to everybody.

Ms. HATHAWAY: (As Kym) Who said it is?

Ms. DEWITT: (As Rachel) I have a life. I'm in school. I'm getting married. I'm...

Ms. HATHAWAY: (As Kym) What?

Ms. DEWITT: (As Rachel) I'm pregnant.

(Soundbite of woman screaming)

Mr. BILL IRWIN: (As Paul) You got pregnant? You are pregnant now?

Mr. MATHER ZICKEL: (As Kieran) Are you sure?

Ms. HATHAWAY: (As Kym) Oh, my God.

Mr. IRWIN: (As Paul) Oh, my God.

(Soundbite of people laughing and screaming)

Ms. DEWITT: (As Rachel) I know, I know, I know.

Mr. ZICKEL: (As Kieran) Are you OK?

Ms. HATHAWAY: (As Kym) That is so unfair.

EDELSTEIN: That is so unfair, Kym says, when Rachel plays that trump card, and the line is so pure in its child-like self-centeredness that it could be a speech balloon in a "Peanuts" cartoon strip.

Demme creates an overlapping texture that evokes the late Robert Altman's films, at once focused and bursting at the seams. And this family drama unfolds in a larger extended family in which racial and cultural barriers have dissolved. The father's second wife, played by Anna Deavere Smith, is African American, and so is Rachel's fiance, Tunde Adebimpe, the lead singer of the band "TV on the Radio."

Late in the film, there's a lengthy musical sequence featuring world musicians as well as Robin Hitchcock and Sister Carol East. I've heard people say that sequence is self-indulgent. It's indulgent, true, but the self has nothing to do with it. Shakespeare's comedies end with songs and dances, and Demme must have felt he needed the celebratory communal interlude to offset the central story, which is bleak and ragged and unfinished.

Debra Winger plays Kym and Rachel's mother, Abby, and when we see her again on screen, it's hard not to smile. She's family. But Abby turns out to be painfully limited, and with Winger on the role, we feel Kym's disappointment acutely. I don't mean Winger is disappointing. The performance is stunning with its layer of maternal warmth over a layer of fear. I mean, when Winger's face hardens and becomes mask-like, it evokes feelings we've all had when people we love didn't rise to comfort us. I don't think I've seen a movie with this mixture of desolation and fullness. "Rachel Getting Married" is a masterpiece.

BIANCULLI: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

95339811

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.