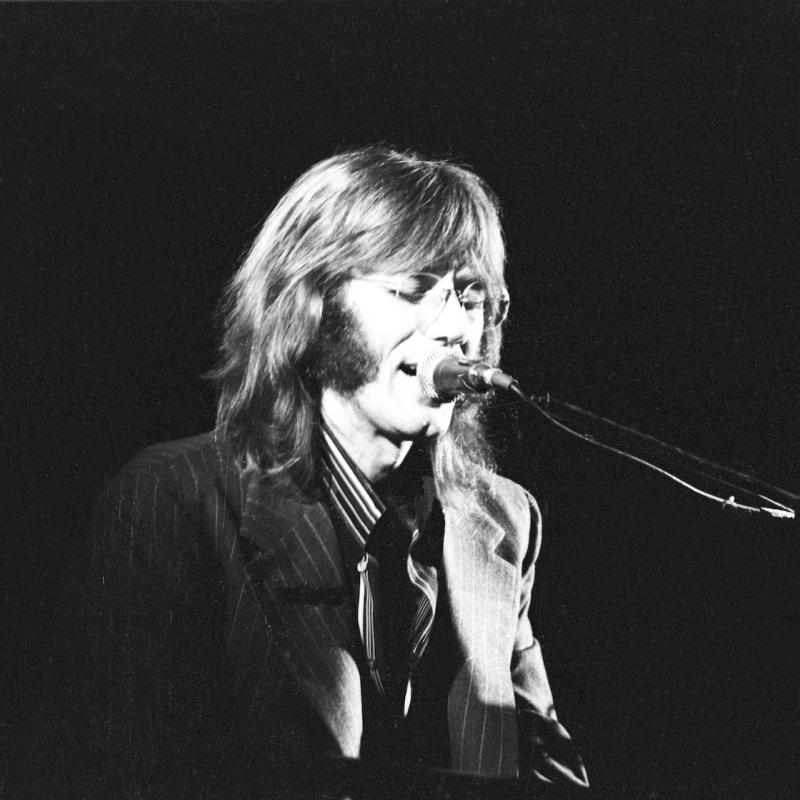

Ray Manzarek of 'The Doors'

Keyboard player and record producer Ray Manzarek was part of the rock band The Doors, which broke up after the death of lead singer Jim Morrison. This month marks the 40th anniversary of the band's formation. There's a new book out next month called, The Doors that gives an inside look at the band. It includes interviews with the three surviving members. Never before seen photos and previously untold stories are revealed.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 20, 2006

Transcript

DATE October 20, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Ray Manzarek talks about Jim Morrison, how the band

group The Doors was formed and his being the band's keyboardist

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Our executive producer Danny Miller has told me he thinks one of the smartest

moves I ever made was convincing Ray Manzarek of The Doors, who played all

those now-classic organ solos to do our interview at the piano. With The

Doors yearlong 40th anniversary celebration about to begin, what a perfect

opportunity to listen back to Manzarek!

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. JIM MORRISON: (Singing) "Yeah!"

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: The mythology surrounding The Doors has mostly centered around its

lead singer, Jim Morrison, who died under mysterious circumstances in 1971 and

is still considered one of rock's tortured poets and sex gods. But

instrumentally, The Doors' distinctive sound was based on Manzarek's keyboard

playing.

(Soundbite from The Doors' "When the Music Is Over")

Mr. MORRISON: (Singing) "When the music's over, when the music's over, yeah.

When the music's over, turn out the lights, turn out the lights, turn out the

lights. Yeah. Yeah."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: I spoke with Ray Manzarek in 1998 after the publication of his book

about The Doors.

Mr. RAY MANZAREK: Biblically, 40 days and 40 nights after we said our

goodbyes after graduation, I'm sitting on the beach wondering what I'm going

to do with myself. Who comes walking down the beach but James Douglas

Morrison, looking great, lost 30 pounds, was down to about 135, six feet tall,

Leonardo--Michelangelo's "David." He had the ringlets and the curly hair

starting to kind of fall over his ears in gentle locks. And I thought, `God,

he looks just great!' And I said, `Jim, Jim, come on over here, man. Come on.

It's Ray. Hey, come on.' He said, `Ray, oh, man! Good to see you.' And, you

know, we did, `Hey, buddy,' `Hey, pal,' you know, high-five and all that kind

of stuff that guys do. And I said, `Well, what have you been up to?' And he

said, `Well, I decided to stay here in Los Angeles.' I said, `Well, good, man,

cool. Tell me, so what's going on?' And he said, `Well, I've been living up

on Dennis Jacobs' rooftop, consuming a bit of LSD and writing songs.' And I

said, `Whoa, writing songs! OK, man, cool! Like, sing me a song,' you know,

and he said, `Oh, I'm kind of shy,' because I knew he was a poet. He knew I

was a musician.

And I said, `Sing me a song.' So he sat down on the beach, dug his hands into

the sand and the sand started streaming out in little rivulets, and he kind of

closed his eyes and he began to sing in a Chet Baker haunted whisper kind of

voice. He began to sing "Moonlight Drive," and when I heard that first

stanza, `Let's swim to the moon, let's climb through the tide, penetrate the

evening that the city sweeps to hide,' I thought, `Ooh, spooky and cool, man.

I can do all kinds of stuff behind that. I could do kind of...'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Sort of like, let's swim to the moon, you know. Let's climb

through the tide...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...penetrate the evening that the city sweeps to hide.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I thought, `Ooh, I can put all jazz chords and I can put

some kind of bluesy stuff.'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: I thought, `Yeah.'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I could do my Ray Charles, you know, and my Muddy Waters,

Otis Spann influences, and I could do just all kinds of bluesy, funky stuff

behind what Jim was singing. And then he had a couple of other songs, "My

Eyes Have Seen You" and "Summer's Almost Gone," and they were just--they had

beautiful melodies to them that would just allow for chord changes and

improvisations. And I said, `Man, this is incredible. Let's get a rock 'n'

roll band together,' and he said, `That's exactly what I want to do.' And I

said, `All right, man. But one thing, what do we call the band? It's got no

name. We can't call it Morrison and Manzarek. I mean, you know, M&M or, you

know, Two Guys from Venice Beach or something.' He said, `No, man, we're going

to call it The Doors.' And I said, `The what? That's ridiculous. The

Door--oh, wait a minute. You mean like the doors of perception, the doors in

your mind.'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And the light bulb went on and I said, `That's it, The Doors

of Perception.' He said, `No, no, just The Doors.' I said, `Like Aldous

Huxley.' He said, `Yeah, but we're just The Doors,' and that was it. We were

The Doors.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's how the band got formed.

GROSS: So when you and Jim Morrison decided to create a band, that left--the

lead singer and keyboard player, you still needed other musicians.

Mr. MANZAREK: Yep.

GROSS: So you ended up finding the drummer, John Densmore, and guitarist

Robby Krieger, but you became not only the keyboard player, but the bass

player, too. It was kind of...

Mr. MANZAREK: Well, it was of necessity.

GROSS: Tell us that story.

Mr. MANZAREK: We had the four of us. I found John and Robby in the

Maharishi's meditation...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and kind of an Eastern mysticism. We were into the same

kind of yoga that The Beatles were into.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that came out of--the song "This Is the End" comes out of

that. So we were all seekers after spiritual enlightenment, and so was Jim,

of course. But we didn't have a bass player, so I applied my boogie-woogie

background, my rock 'n' roll boogie-woogie, because when I discovered

boogie-woogie...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...that was the whole thing. And you just keep that left hand

going. You don't do anything with it. It just goes and goes and goes and

goes.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And the right hand does the improvisations.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So I had done that over and over and over as a kid, so it was

very easy for me to--once we found the Fender Rhodes keyboard bass, 32 notes

of extra-low sounding low notes, it was very easy for me to do...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So that's what I did on the piano bass.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Or like "Riders on the Storm"...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's what I did. I just over and over, repetitive bass

lines that are just like boogie-woogie, just keeps on going.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And it becomes hypnotic, and that's why Lefty here is--thank

you--he did a very good job. He's not too quick.

GROSS: So...

Mr. MANZAREK: He's a bit of a slow-witted fellow, Lefty, but he's really

strong and solid and plays what he has to play, so Lefty became our bass

player.

GROSS: So your left hand and right hand were playing separate keyboards.

Mr. MANZAREK: Oh, of course. Yeah. I had a Fender Keyboard Bass sitting on

top of a Vox Continental Organ, and the Vox Continental Organ was what I

played with my right hand and the Fender Keyboard Bass with my left hand.

(Soundbite The Doors' "Love Me Two Times")

Mr. MORRISON: (Singing) "Love me one time, could not speak. Love me one

time, baby. Yeah, my knees got weak. Love me two times, girl, last me all

through the week. Love me two times, I'm going away. Love me two times,

babe. Love me twice today. Love me two time, babe, because I'm a-going away.

Love me two times, girl, one for tomorrow, one just for today. Love me two

times, I'm going away. Love me two times, I'm going away. Love me two times,

I'm blown away.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's The Doors' "Love Me Two Times." You're listening to a 1998

interview with Ray Manzarek, who was the band's keyboard player. The Doors

history is filled with stories about the unpredictable behavior of lead singer

Jim Morrison. One of those stories is about what happened during the "Light

My Fire" recording session. The engineer, Bruce Botnick, had brought in a

television and put it in the studio, and when Morrison noticed it, he

exploded. I'll let Manzarek tell the story.

Mr. MANZAREK: Bruce Botnick has the Dodgers on. The Dodgers are in the

pennant race. Bruce Botnick's a big baseball fan. Sandy Koufax is pitching,

the king, one of the great pitchers of all time. He's recording with The

Doors. He brings his portable television set. He wants to see the game.

It's the middle of the afternoon. Dodgers are playing and he's got his

television. He couldn't put it in the control room. There's too much

electronic equipment and it just--with the rabbit ears. These are the old

days, folks. This is before cable. This is--people had rabbit ears coming

off of the television set. He couldn't do it in the control room, too much

electronic equipment, too much static. He found a good place for it off to

the side in the studio area, facing the window, the control room window. It

wasn't in anybody's way or anything. Everything was fine. So we're in the

middle of "Light My Fire," and it's solo time, and I'm about to go Coltrane...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and do my stuff and Jim comes out of the control room--or

out of his vocal booth. You put the singer in a vocal booth and he starts

dancing around. He's having a great time. Then he comes over to the TV set

and he sees the TV set, then he looks around and notices that it's on.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeow, God, he freaks out. It's like, `What is a TV set on in

the recording studio? We're making Doors music here for the first time--this

is our first recording session. First time in our lives, we're in the studio.

We're doing "Light My Fire" and a baseball game is on the TV set?' Jim picks

up the TV set, unplugs the damn thing and hurls it at the control room window.

We freak, man. Everybody just--we're in the middle of--I'm just going to

town...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and all of a sudden it's like, `Ahhhhh, Jim, whoa, no, God,

don't throw it at the...(unintelligible)!'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Hits the control room window. Thank God, the control room

window is double-thick glass. Bounces off the control room window, falls on

the floor and shatters in 500 pieces.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that was the end of the session. And Bruce Botnick comes

running out and says, `Jim, what have you done?' And Jim says, `What's this TV

set doing here, Bruce?' `I was just watching the baseball game. That's

my--you brok--that's my TV set.' And Jim said, `No TV sets in the recording

studio ever!'

GROSS: You also write in your memoir, "Light My Fire," about--you know, Jim

Morrison's period as like a sexual god and you write about how like he'd wear

his leather pants with no underwear so the contours of his manhood can be...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yes.

GROSS: ...could be seen under the leather. I'm wondering what it was like

for you to kind of be at the epicenter of this kind of like sexual adoration.

Mr. MANZAREK: Oh, it was fabulous. It was fabulous. I mean, we made our

music. That's what we did. You know, the fact that Jim attracted the little

girls was something that I knew he was going to do when I saw him at 135

pounds on the beach. `We're going to start a rock and roll band, and you're

about the handsomest guy I've seen.' I didn't say that to him. `The girls are

going to love this guy.' And the girls did love him.

GROSS: We're listening back to a 1998 interview with Ray Manzarek, who was

The Doors' keyboard player.

We'll hear more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Ray Manzarek just told us some stories about Jim Morrison's

destructive behavior. So how did the head of the record company feel about

that? We're about to hear the answer from Jac Holzman, the founder of The

Doors record company, Elektra Records. I spoke with Holzman in 1998 after the

publication of his book about Elektra called "Follow the Music." Elektra

started out as a folk and ethnic music label and first made its mark with such

performers as Jean Ritchie, Theodore Bikel, Judy Collins, Tom Paxton and Phil

Ochs. Elektra's first big hit was The Doors' single "Light My Fire." What

attracted a folk and classical music fan like Jac Holzman to The Doors? Well,

one thing was "Whiskey Bar," The Doors' version of a Brecht-Weill song.

(Soundbite from The Doors' "Whiskey Bar")

THE DOORS: (Singing) "Oh, show me the way to the next whiskey bar. Oh, don't

ask why. Oh, don't ask why. Show me the way to the next whiskey bar. Oh,

don't ask why. Oh, don't ask why. For if we don't find the next whiskey bar,

I tell you we must die, I tell you we must die, I tell you, I tell you, I tell

you we must die. Oh, moon of Alabama, we now must say goodbye. We've lost

our good old mama and must have whiskey, oh, you know why. Oh, moon of

Alabama, we now must..."

(End of soundbite)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Jac Holzman, founder of Elektra Records, talks about

working with Jim Morrison of The Doors

TERRY GROSS, host:

I asked Jac Holzman about the difficulties he faced working with Jim Morrison,

who was talented, commercially successful, but often out of control.

Mr. JAC HOLZMAN: From our standpoint, the difficulties in Jim's life and the

way he expressed them were nothing as compared to the magic of the recordings.

It was more than "Light My Fire." The first Doors album was as close to a

perfect album as I've ever been involved with. That album really pushed the

envelope, and I was just so thrilled to be associated with it, and if there

was a price to pay, that was OK with me. I had dealt with some outrageous

artists before who had problems and artists afterwards who had problems, and I

found it best to keep my distance because I am the person who runs their

record company and I am the surrogate for the audience, and it's my job to

make sure that things keep moving and that the artists are given the very best

possible circumstances in which to record, and these are the issues that you

expect you have to deal with.

GROSS: So you tried to keep your distance in part so you could remain kind of

the authority figure and not get to close with anyone.

Mr. HOLZMAN: Well, it makes it difficult if at some point you have to take a

stand on something and you've been hanging out with them all the time. It

erodes the special relationship that you have with them, and I think that The

Doors appreciated that. I know Jim did. Before he went to Paris he wanted to

have sort of a farewell drinking session with me. Well, I'm smart enough not

to have more than two with Jim Morrison because Jim's big enemy was alcohol,

and he could be a prince, you could take him anywhere, but pour a few drinks

into Jim and he would go from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde, and it was a real

problem, so I would never try to match him drink for drink, but I remember

this evening so vividly because we're sitting in this bar and we've each had

our second drink, and Jim begins to taunt me. `Jac, you've got to go more out

on the edge.' And I responded, `Jim, it's great being on the edge. The trick

is not to bleed.' And he sort of paused for a moment, and then we talked about

movies.

GROSS: Now why did you decide to sign The Doors. What appealed to you about

their music?

Mr. HOLZMAN: I went to see another group called Love who was on Elektra, and

Arthur Lee, who was the essential linchpin of that group said, `Stick around

for the other group that's on the bottom of the bill.' And I did, and I wasn't

really very impressed. But there was something about the group that kept

bringing me back, and it was only later that I figured out what it was. It

was a kind of austerity in their musical line. If I were to compare The Doors

to architecture, I would say that they were the bowhouse of '60s rock and

roll, and I think that cleanliness of line and the expressive lyrics and the

sheer beautiful simplicity of it is what has made the group last for over 30

years.

GROSS: When you found out about Jim Morrison's death, what responsibilities

did you have? Did you have to take care of his personal effects or anything

like that?

Mr. HOLZMAN: No, what I had to take care of first was my own emotion. Jim

had been so special to me and the band was phenomenal, and they had played

such a vital and pivotal role in the growth of Elektra. Jim had been kind to

me and my family. He would remember my son Adam's birthday and bring him a

musical instrument and spend time with him. So I had to deal with that. But

I also realized that I had to deal with what I thought was going to be a media

circus, and indeed it had been for Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, but I was

lucky. I had two days to prepare. I knew about it on a Monday and it wasn't

public knowledge until Wednesday evening so I sent my number two man, Bill

Harvey, out to the West Coast. We had press releases prepared. We told the

staff at the appropriate time. We had to tell Paul Rothschild who had been

their producer for all the albums except the final one, "LA Woman." And we got

all of that stuff done, so when the phone calls started coming and people

wanted the radio interviews, we had determined that we were going to let The

Doors do most of the talking, The Doors and Pam, and we would speak only about

what their music meant to us and to their fans.

GROSS: Jac Holzman founded Elektra Records, which recorded The Doors. We'll

hear more from Doors keyboard player Ray Manzarek in the second half of the

show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite from The Doors' "People Are Strange")

THE DOORS: (Singing) "People are strange when you're a stranger, faces look

ugly when you're alone. Women seem wicked when you're unwanted, streets are

uneven when you're down. When you're strange, faces come out of the rain.

When you're strange, no one remembers your name. When you're strange, when

you're strange, when you're strange. People are strange when you're a

stranger, faces look ugly when you're alone. Women seem wicked when you're

unwanted. Streets are uneven when you're down."

(End of soundbite)

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Filler: By policy of WHYY, this information is restricted and has

been omitted from this transcript

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: The Doors keyboard player Ray Manzarek talks about

how the group started doing "Light My Fire"

TERRY GROSS, host:

We're getting a jump today on The Doors' 40th anniversary celebration which

officially begins next month. Let's get back to the interview I recorded in

1998 with Doors keyboard player Ray Manzarek. He sat at our piano.

In your memoir, you write a lot, really, about how The Doors developed their

sound and how you developed your sound as the keyboard player with the group.

Let's take an example...

Mr. RAY MANZAREK: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...of one of those songs. Why don't we look at "Light My Fire"...

Mr. MANZAREK: Sure.

GROSS: ...which is probably the most famous or one of the most famous...

Mr. MANZAREK: The most famous Doors' song. Yeah.

GROSS: Sure. Yeah.

Mr. MANZAREK: The most famous Doors' song. You know, it's that worldwide

popular appeal, most famous. And Robby Krieger's actually the writer of

"Light My Fire." So the way we would work on songs is somebody would bring a

song in, and then everyone would go to work on it. It would be like little

bees just--or little things spinning and working and weaving. So Robby came

in with a song. He said, `I've got a new song called "Light My Fire."' The

first song Robby Krieger ever wrote. What a genius he is! He's just the

greatest guy. Great guitar player and great songwriter. `I've got a song

called "Light My Fire."' so he plays the song for us, and it's kind of a Sonny

and Cher kind of, `Dun, da, dun, da, dun, da, da, da, da, dun, dah, light my

fire.' And I was like, `OK, OK, good chords. You know, what are the chord

changes there?' and he shows me, an A-minor...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...to an F-sharp minor.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's like, whoa, that's hip.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: That's cool. And then...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's when he went into the Sonny and Cher part.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Da, da, da, da, da, da, da. And we said, `No, no, no, no, no,

no, we're not going to do this Sonny and Cher kind of song here, man.' And

that was popular at the time. Densmore says, `Look, we've got to do a Latin

kind of a beat here. Let's do something in kind of a Latin groove.'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I'm doing this left-hand line. So John's doing

ka-ka-chooka-chooka doo-dah, you know. And we set up this Latin groove and

then go into a hard rock four...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And Robby's only got one verse. He needs a second verse, and

Morrison says, `OK, let me think about it for a second,' and Jim comes up with

the classic line, `And our love becomes a funeral pyre.' You know, `You know

that it would be untrue, you know that I would be a liar if I were to say to

you, "Girl, we couldn't get much higher"' is Robby's, and Jim comes, `The time

to hesitate is through.' In other words, seize the moment. Seize the

spiritual LSD moment. `The time to hesitate is through. No time to wallow in

the mire. Try now, we can only lose.' Whoa! That's kind of heavy. `Try now,

we can only lose,' meaning the worst thing that can happen to you is death,

`And our love becomes a funeral pyre.' Our love is consumed in the fires of

agony. And it's like, `God, Jim, what a great verse, man!'

So we've got verse, chorus, verse, chorus, and then it's time for solo. So

anyway, the verse goes, `Time to...'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...eh, ah, doo, dah--you know how that goes. You've heard it

a million times.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And then into the chorus, `Come on, baby, light my fire.'

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So it's time then for some solos. We've done a verse, chorus,

verse, chorus. Now what do we do? We've got to play some solos. We've got

to stretch out. Here's where John Coltrane comes in. Here's where The Doors'

jazz background--John's a jazz drummer. I'm a jazz piano player. Robby's a

flamenco guitar player. And we all said, `You know, we're in A-minor. Let's

see, what do we do?' Da, da, da, da, da.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: It ends up on an E, so how about...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: "My Favorite Things," John Coltrane. It's "My Favorite

Things," except Coltrane's doing it in D-minor...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: But the left hand is exactly the same thing.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: It's in three, one, two, three, one, two, three, A-minor. The

Doors' "Light My Fire" is in four. We're going from A-minor to B-minor.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So it's the same thing as...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And that's how the solo comes about, and then we just go...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So it's John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things."

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And Coltrane's "Ole Coltrane" and then...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: That's the chord structure. Then I would solo over it.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Robby would solo over it, and at the end of our two solos,

we'd go into a...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...three against four...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and I'm keeping the left hand going exactly as it goes.

That hasn't changed. That's the four. On top of it is three.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And into the turnaround.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And we're back at verse one and verse two.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And we're back into our Latin groove, so it's basically a jazz

structure. It's verse, chorus, verse, chorus, state the theme, take a long

solo, come back to stating the theme again. And that's how "Light My Fire"

came about. The only thing left to do was to come up with that little

turnaround thing. I hadn't had that yet. And we said, `Now how do we start

the song? Do we just jump on an A-minor to an F-sharp? You know, are we

going to do that? Vamp a little bit?' I said, `No, no, no. We need something

more. We can't just vamp a little bit.' And I started--I put my Bach back to

work, put my Bach hat on and came up with a circle of fifths.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So I started like this...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Like a Bach thing, like...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: So same kind of thing.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. B-flat, so I'm in G, D,

F, up to B-flat...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...E-flat...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...A-flat to the A to A-major, A-major. Yeah. That's it.

And then we'll go to the A-minor. I'm thinking all this to myself. So that's

how the introduction came about.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: F, B-flat, E-flat, A-flat, A...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and the drums and everything. Jim comes in singing.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And the Latinesque and then into hard rock. So that's how

"Light My Fire" goes. That's the creation of "Light My Fire."

GROSS: And you come up with this great organ solo in the middle...

Mr. MANZAREK: Oh, that was just luck.

GROSS: ...which is, of course, cut out of the single.

Mr. MANZAREK: Right, exactly.

GROSS: Because your producer figured, we've got to get this on the radio.

Mr. MANZAREK: Right.

GROSS: So we've got to do a singles version...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah. We had to cut down six...

GROSS: ...and it was--what?--six or seven-minute track.

Mr. MANZAREK: ...seven minutes--we had to cut down seven minutes to two

minutes and--under three minutes, you know, two minutes and 45 seconds, 2:50

would be ideal.

GROSS: So he calls you into the office, plays you his version...

Mr. MANZAREK: Yeah. Well...

GROSS: ...his edited version.

Mr. MANZAREK: ...Paul Rothschild, a brilliant genius, producer, and Bruce

Botnick was our engineer. Those two guys were--those were Door number five

and Door number six. Without those two guys--there were six Doors in the

recording studio, the four musicians and Paul Rothschild and Bruce Botnick.

Without them, we never would have done nearly what we did. Paul said, `I'm

going to make an edit here. I'm going to do some edits. I'm going to cut

"Light My Fire" down from seven minutes to 2:45, 2:50,' and I said, `Good

luck, man. I don't see how you're going to do it.' There's solos, Robby's

solo, my solo, all this stuff. I mean, you're gonna have to do--I figured

he's going to have to do little bits and cuts and here and there and just

little tiny, little incisions, like the Chinese torture of a thousand cuts is

what he was going to have to do. You actually had to cut tape in those days.

No computers, so you actually cut the tape. Two days later, Rothschild calls

and said, `OK, man, I got it.' I said, `You got it? How did you do it so

fast? You've got a thousand cuts.' And he said, `No, no, no. Just come on

in. I'm not going to tell you what I did, how I did it. I just want you to

listen to it.'

So the song starts. We're all in the control room on the big speakers at

Sunset Sound. The song starts...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: We're at the regular introduction and then it's into...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and it's going along and then `Come on, baby, light my

fire.' And that's going along. Now we're into the second verse. `The time to

hesitate is through, no time to wallow in the mire. Try now, we can only

lose. Our love becomes a funeral pyre.' Everything's going exactly--`Come on,

baby, light my fire.' Nothing has changed. Everything is exactly the same.

`Come on, baby, light my fire. Try to set the night on fire.' Now it's time

for the solos. I think, `Where's the edit, man?' And we're into the solos.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I thought, `I don't know where he's going to cut. This is

insane.' And, all of a sudden, where I'm supposed to go...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...you know, play my organ solo, what happens, it goes...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...it goes to the end of the solos...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: ...and then back into the turnaround, and there's like not a

solo. There's no solos--I'm out. I've got three minutes of solo. Robby's

got two and a half minutes of solo. It's all gone. It just goes, dah, dah,

dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah, and turnaround...

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And I think, `Oh, no, what's'--and then we go back into verse

number three.

(Manzarek playing piano)

Mr. MANZAREK: And then we do that exactly as the song is, and then verse

number four. `It's time to hesitate, no time to wallow in the mire. Our love

becomes a funeral pyre. Come on, baby, light my fire. Come on, baby, light

my fire. Try to set the night on fire, try to set the night on fire, try to

set the night on fire.' And it's the end of the song, and that's it. It's two

minutes and 45 seconds long, and there are no solos in the entire song, and I

thought, `I'm going to kill this guy.' Or I looked at Robby and Robby said,

`You want to kill him? Let's kill him.' And Paul said, `Hold it, hold it.

Listen, I know the solos aren't there, but just think. You don't know the

song. You've never heard the song. You're 17 years old. You're in

Poughkeepsie, you're in Des Moines, you're in Missoula, Montana, you've never

heard of The Doors. All you know is a two-minute and 45-second song is going

to come on the radio. It's called "Light My Fire." Does that work?' And we

all looked at each other and said, `You know what, man? You're right. It

does. It works.'

(Soundbite from The Doors' "Light My Fire")

THE DOORS: (Singing) "You know that it would be untrue, you know that I would

be a liar if I was to say to you, `Girl, we couldn't get much higher.' Come

on, baby, light my fire. Come on, baby, light my fire, try to set the night

on fire. The time to hesitate is through..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Ray Manzarek was recorded in our studio in 1998. Next month a new

book will be published about The Doors, written by the surviving members and

Ben Fong-Torres, and Rhino Records will release The Doors box set. This is

all part of The Doors' 40th anniversary celebration.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Film critic David Edelstein reviews Clint Eastwood's

new movie, "Flag of Our Fathers"

TERRY GROSS, host:

After Clint Eastwood won an Oscar for directing "Million-Dollar Baby" the

76-year-old screen legend began work on his most ambitious project: two

films, shot back-to-back, that revolve around the blood battle of Iwo Jima.

The first, "Flag of Our Fathers," opened today. David Edelstein has this

review.

Mr. DAVID EDELSTEIN: Some critics regard Clint Eastwood as an American old

master. His direction, like a great jazz musician's affectless cool. I find

it, with exceptions, a mixture of the limp and the hamhanded. But "Flags of

Our Fathers" is one of those exceptions. The storytelling is clunky as usual,

but Eastwood has never directed sequences as fluid and poetic and profoundly

disturbing. The movie is adapted from the best seller by James Bradley, with

Ron Powers, and it's another elegy to the World War II greatest generation.

But there's a critique of the culture built in. At its center is the immortal

Joe Rosenthal photograph of five men, their faces obscured, struggling to

raise a flag at the top of Mount Suribachi on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima,

one of the most inspiring images ever captured. Without discrediting the

power of that image, the movie, like the book, goes on to expose its petty

genesis and its dispiriting aftermath.

The film begins with a voiceover. Harve Presnell, sounding eerily like Bob

Dole, asserts, `Every jackass thinks he knows what war is.' What follows is a

scene so painful that it's hard to wrap one's mind around it. A medic, played

by Ryan Phillippe tries to keep an American soldier's innards from spilling

out. Suddenly, a Japanese soldier leaps over a ridge and the medic grinds his

own bayonet into the enemy's stomach. That mirror image nightmare isn't

carried through the rest of the film, but everything that follows is suffused

by it, and by the irreconcilability of the fact of war, with slogans meant to

sell bonds.

Eastwood's co-producer is Steven Spielberg, and there are similarities between

the slaughters on the beach of this Iwo Jima and the Omaha of "Saving Private

Ryan." But the way that Eastwood backs off from the splattery spectacle

strikes me as a mark of decency. The carnage is intense enough to haunt you,

but not relentless enough to punish you. Eastwood leaches the color out of

the frame, leaving a sickly green, and he's composed a melancholy score that

makes even victory seem like loss. We rarely glimpse the tens of thousands of

Japanese hidden in tunnels in that mountain so the bloodshed is disconnected.

Eastwood shot another film simultaneously, "Letters from Iwo Jima," from the

Japanese perspective. In that movie, opening in the near future, he'll take

us inside Suribachi. "Flags of Our Fathers" appears at first to be at cross

purposes with itself. It says the men who returned from war were not heroes

and then goes on to show them sacrificing themselves for one another with what

seems like superhuman heroism. That's where the photo comes in. The mystery

behind that flag planting is carried by its three surviving subjects, played

by Phillippe, Jesse Bradford and Adam Beach, none of whom feels entitled to

the adulation they receive on the homefront. There's a trace of "the right

stuff" in the depiction of so-called real men who blanch under the efforts of

their handlers' marketing. But those astronauts weren't eaten up alive by

survivors' guilt. And there's another issue here. There were two photos, and

one of the soldiers in the famous one, which is actually a recreation, has

been misidentified. That weighs most heavily on Beach's Ira Hayes as he

listens to his handler, played by John Slattery.

(Soundbite from "Flags of Our Fathers")

Mr. JOHN SLATTERY: (As Bud Gerber) So we've got a hell of a lot of money to

raise and not a lot of time. White House tomorrow, then we trot you over to

shake hands with a couple of hundred congressmen who won't pull a penny out of

their pockets. Politicians and actors--put them in a restaurant together and

they die of old age before picking up the check. Then New York City, Times

Square, dinners with various hoi polloi, then Chicago.

Mr. ADAM BEACH: (As Ira Hayes) Who are these gold-star mothers?

Mr. SLATTERY: That's what we're calling the mothers of the dead

flag-raisers. You present each mother with a flag. They say a few words.

People (censored) money. It will be so moving.

Mr. BEACH: (As Ira Hayes) But this is Hank Hansen's mom.

Mr. SLATTERY: Lovely woman. She knows how close you and her son were. He

wrote home about you. She is very, very much looking forward to meeting you.

Mr. BEACH: (As Ira Hayes) Hank wasn't in the picture.

Mr. SLATTERY: Sorry?

Mr. BEACH: (As Ira Hayes) Hank didn't raise that flag. He raised the other

one. The real flag.

Mr. SLATTERY: Huh? The real flag? There's a real flag?

Unidentified Man: Yeah. Ours was the replacement flag. We put it up when

they took the other one down.

Mr. SLATTERY: Am I the only one getting a headache here? You know about

this?

Man: It was after. It was already in the papers. The mothers had already

been told but...

Mr. SLATTERY: That's it. That's beautiful. Yeah. That's beautiful. Yeah.

Why tell me? I'm only the guy who has to explain it to 150 million Americans.

(End of soundbite)

Mr. EDELSTEIN: It's when the movie gets into the specifics of the men's

guilt that the familiar Eastwood seams show. As Hayes, a native American

whose feelings of inadequacy, reinforced by rampant prejudice against his

people, drives him further into drunken disillusionment, Beach emotes in a

vacuum. It's the sort of performance that gets nominated for awards, because

you can't escape the acting. Ryan Phillippe is a study in colorlessness, and

many of the soldiers blur together. But the infelicities don't matter

finally. "Flags of Our Fathers" fits into Eastwood's late-in-life agenda, to

make violence, even in self-defense, seem soul-killing and to expose the gulf

between the reality and myth. After this, how can we ever again make our

peace with the iconography of war?

GROSS: David Edelstein is film critic for New York magazine.

(Soundbite of music)

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of music)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.