Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on March 7, 2008

Transcript

DATE March 7, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

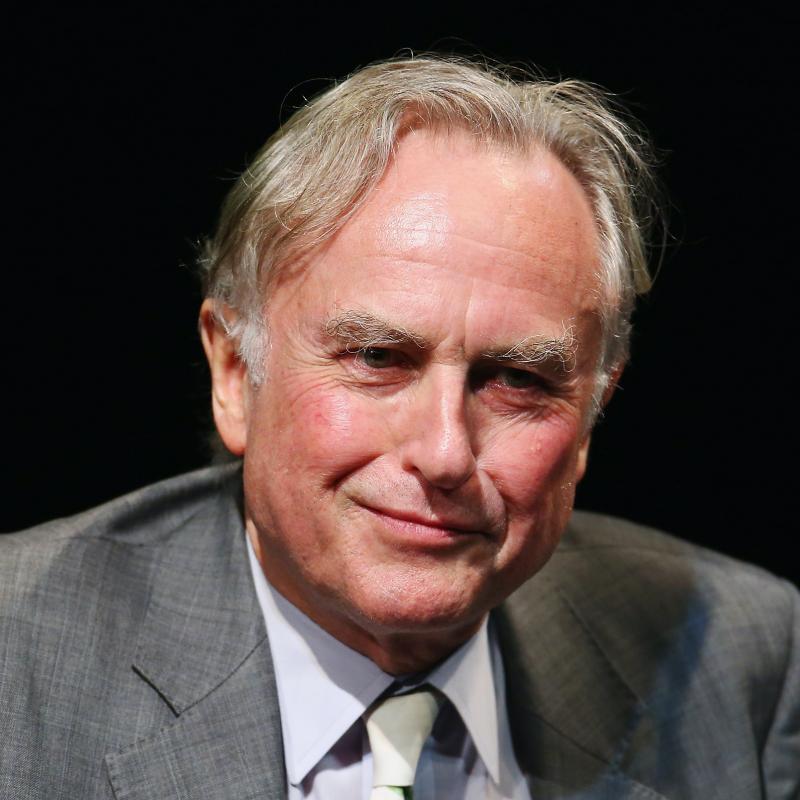

Interview: Richard Dawkins, evolutionary biologist and author of

"The God Delusion," on his atheism, creationism vs. evolutionary

biology, and the logical unnecessity of a sentient God

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Can you be a scientist and believe in God? Are science and religion

compatible? We're going to get two very different responses to that question

from two scientists. On the second half of our show, I'll speak with Francis

Collins, who headed the human genome project, which mapped the genetic code of

human beings. He's an evangelical Christian and believes that, in studying

DNA, he is finding God's code.

But first we'll hear from Richard Dawkins, a British evolutionary biologist

and the author of the controversial best seller "The God Delusion," which has

just come out in paperback. He's an atheist and proud of it. He says the God

hypothesis--that there is a supernatural intelligence who deliberately

designed the universe and everything in it--is a scientific hypothesis that

should be analyzed as skeptically as any other. Dawkins is a professor of the

Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University.

Do you feel particularly strongly about atheism because your branch of

science, evolution, has come under attack by certain Christian fundamentalists

who think evolution violates their religion?

Mr. DAWKINS: Yes. My subject of biology is quite difficult for people to

teach in America now at the school level. I think it's not so bad at

university because at university, I mean, most universities take evolution

seriously and seem not to be under the control of local school boards.

However, there are constant rumors, and more than rumors, of teachers all

throughout the United States being intimidated by parents, by local school

boards, even by the children they're trying to teach, and prevented by

intimidation from teaching their own subject, from teaching their science, the

science of evolution. And that obviously is very disquieting to any

biologist, and I'm no exception.

GROSS: Now, of course, not all religion and not even all Christian

fundamentalists disapprove of evolution or teaching evolution.

Mr. DAWKINS: No. Yeah, it's very important to say that, and I'm glad you

raised that because it's one of the unfairnesses that religious people who are

sensible--I mean, relatively sensible religious people who of course accept

evolution just as much as I do and get very annoyed at being tarred with the

same brush as the fundamentalists, many of whom actually literally believe the

world is only 6,000 years old, and which is--I mean, it should be a joke but

for the fact that some 50 percent of the American population believe it. But

it is important, as you say, and as I often say, to stress that not all

Christians are of that dotty opinion.

GROSS: Now, compare that opinion with yours, where those two figures come

from.

Mr. DAWKINS: Oh, do you mean the true age of the universe?

GROSS: Exactly. Yes.

Mr. DAWKINS: The true age of the--the currently established age of the earth

is 4.6 billion years. If you compare that with 6,000 years, it's equivalent

to believing that the distance from, say, Philadelphia to San Francisco is

about seven yards.

GROSS: And the 6,000 years comes from?

Mr. DAWKINS: It comes from the Bible. It comes from looking up all those

begats. So-and-so begat so-and-so who begat so-and-so, and their ages are

given. Add the ages up together and you come up with a date of 4004 BC for

the origin of the world--indeed, of the universe.

GROSS: Do you think that religion and evolutionary biology ask a lot of the

same questions, but come up with different answers?

Mr. DAWKINS: Well, I do think that, and not all my scientific colleagues do.

There is a movement among scientists to say that religion and science are

about totally different things and they sort of don't impinge on one another

and they're both equally true in their own sphere. I don't hold to that view.

I think they're about the same thing, in the sense that they both aspire to

explain the universe. They both aspire to explain why we're here. What's the

meaning of life? What's it all about? What's the role of humanity? And so

on. I think that all those questions are susceptible of a scientific

explanation. Traditionally, religion has always given the explanation for

those--the answer to those questions, wrongly, and so my attitude is rather

different from that voguish scientific attitude that there's no overlap. I

think there's plenty of overlap, it's just that religion gets it wrong.

GROSS: What do you mean by that, that religion gets it wrong?

Mr. DAWKINS: Well, I mean, obviously in the case of evolution, but as we've

seen, that doesn't apply to all Christians. My point, when I try to say that

religion and science are about the same thing, is that a universe with a God

would be, scientifically speaking, a very different kind of universe from a

universe without a God. It is a scientific question whether there is a

gigantic intelligence somewhere at the root of the universe. Either there is

or there isn't. It's not a sort of poetic matter, it's a scientific matter.

Either there is or there isn't a God. It may be very difficult to decide the

question. I make an effort to look at the probability. I'm quite convinced

you can't disprove the existence of God, but I think you can put a probability

value on it, and I think the probability is very low.

GROSS: You know, some people see God as a more mystical, like unknowable,

invisible, unnameable presence that somehow holds the universe together and

gives it meaning and expression and beauty and everything else that it has,

but would be invisible to the tools that science has to investigate the world.

Mr. DAWKINS: Let me make a distinction between two versions of what you've

just said. There's what I would call the Einsteinian version, which pays

homage to the mysteries that lie in the universe at the base of physics, the

mysteries that physics has yet to solve and may never solve. Einstein had

immense reverence for that, as do I. Einstein used the word "god" for the

deep problems, for those fundamentals which we don't understand and may never

understand.

But I would want to make a distinction between that Einsteinian view and the

one that says there is a spirit which has some sort of intelligence; there is

a supernatural, intelligent, creative being who created the universe and made

up its laws. I think that's radically distinct from the Einsteinian view that

the laws of physics are renamed God. And I have no quarrel with somebody who

wants to use the word God for the fundamental laws of the universe. My only

quarrel would be that it's confusing to everybody else. But once we've set

confusion on one side, then I have no quarrel with that.

What I do have a quarrel with is people who confuse that with God in the sense

of some kind of supernatural intelligence or creator who worked it out, and I

think there really is a big distinction there.

GROSS: Well, since you brought up Einstein, and since you quote Einstein

several times in your book "The God Delusion," let me ask you to read a few of

the things that you quote by Einstein about religion.

Mr. DAWKINS: Right, well, from page 15 of "The God Delusion":

(Reading) "It was, of course, a lie, what you read about my religious

convictions, a lie which is being systematically repeated. I do not believe

in a personal god and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly.

If something is in me which can be called religious, then it is the unbounded

admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal

it."

And further down the same page, I quoted Einstein as saying, "I am a deeply

religious nonbeliever. This is a somewhat new kind of religion.'

GROSS: So do you consider yourself religious in the Einsteinian sense?

Mr. DAWKINS: Yes, I do consider myself religious in the Einsteinian sense,

and obviously with great humility. Einstein was the greatest scientist of the

20th century and maybe ever, and so I humbly am happy to be classed as in his

camp in this respect.

GROSS: Now, you were saying before that you think religion and evolutionary

biology ask a lot of the same questions but come up with different answers and

approach the whole thing, of course, differently. You think that all life

forms on the planet can be traced to a single ancestor, and that was the

subject of a previous book called "The Ancestor's Tale." Would you just give

us like--this is asking a lot--but a brief kind of layman's explanation of

tracing all living organisms to one creature or organism?

Mr. DAWKINS: Right. The evidence that all living organisms that have ever

been looked at are descended from a single ancestor is mainly biochemical.

It's mainly biochemical genetics and the genetic code. The genetic code by

which DNA is translated into protein--you could call it the machine code of

life--is universal. With very, very tiny differences, every single creature

that's ever been looked at--mammals, birds, spiders, insects, worms, oak

trees, amoebas, bacteria--they all have the same machine code. They all have

the same code that translates from DNA into protein. Now, that, I think,

conclusively demonstrates that they have a common ancestor, which was probably

something, not really a bacterium, but a bacterium might be nearest approach

to it still alive today. It probably lived some four billion years ago.

That's not to say that life has not originated more than once. But if there

have been other origins of life, they have left no descendants. All surviving

life forms are descended from a single common ancestor. That is as certain a

fact as any in biology.

GROSS: Now, I want to quote something that you wrote in "The Ancestor's

Tale," a previous book about evolution. You wrote, "My objection to

supernatural beliefs"--and by that, you mean religion--"is precisely that they

miserably fail to do justice to the sublime grandeur of the real world. They

represent a narrowing down from reality and impoverishment of what the real

world has to offer." In what way do you see religion as an impoverishment over

what the real world has to offer?

Mr. DAWKINS: First of all, I think I should say that "The Ancestor Tale" is

an extremely long book, and I believe that that page that you just read from

is the only place in the entire book where religion is mentioned. I just say

that because I'm sometimes accused of dragging religion in everywhere, so it

is--there's very, very little of that in the book.

Now, dragging down--I think that the understanding of life, and indeed of

science generally, the understanding of the universe generally that we now

have at the beginning of the 21st century, is an astoundingly rich, poetically

valuable, truly wonderful achievement of our species, something that we have

every right to be proud of. You could spend a lifetime imbibing and learning

and understanding and increasing understanding of this view that we now have.

It is incomparably richer than anything that our ancestors in past centuries

could have. It is an enormous privilege to have it. No one individual could

possibly comprehend it. It's a lifetime's worth just to understand bits of

it. And I think it is demeaning to retreat from that to a medieval worldview

which simply says, `God done it,' which is so trite, so cheap, so over simple,

so parochial and so impotent in the face of the huge phenomena which need to

be explained and which now are being explained.

GROSS: Now, I think there are some scientists who are both religious and

scientists and find the two compatible, and I'll give as an example Francis

Collins, who is the head of the human genome project and feels that his

investigation of the genetic code is basically a way, also, of investigating

God's design, that the genetic code is an example of God's intricate design.

Mr. DAWKINS: It's so superfluous, isn't it? I mean, here we have a

beautiful explanation for how life comes about, starting from simple

beginnings, and that makes God redundant, and then Francis Collins and others

want to smuggle God back in and say, `Oh, well, natural selection was God's

way of doing it.' And what's that's saying is that God the designer chose as

his method of design a method which would look exactly as though he wasn't

there. He chose a method which would make himself redundant. He chose the

method that made him superfluous. Why bother to postulate him at all in that

case?

GROSS: My guest is evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, author of the best

seller "The God Delusion." We'll hear more from Dawkins after a break. This

is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. He's an atheist

who finds science and a belief in God incompatible. His best seller, "The God

Delusion," is now out in paperback.

You feel a sense of awe from science and from trying to get to the bottom of

what science has to tell us about the history of the world and every creature

on it. Now, some people would argue that science can help explain how the

species evolved but it can't give meaning to existence, that only religion is

the kind of--the worldview, the lens that you can see life and the world

through that is inherently about giving meaning to life and existence. How

would you answer that?

Mr. DAWKINS: I think the first thing I'd say is that the universe doesn't

owe us meaning. There's no reason why there should be any meaning. It might

be comforting if there is, it might be consoling. It would be nice to think

that there's meaning in everything. But we are not owed meaning. If there

isn't any meaning, there isn't any meaning; and that's just tough.

However, you can make your own meaning in two different ways. One way is a

personal one, and each one of us living our lives can give our lives meaning.

Our lives may have meaning in terms of the work that we do, the art that we

create, the music that we create, the science that we do. All our family

life, our love for our spouse or our children, our love for nature, our love

for some sport. There are all sorts of ways in which we can give our own

lives meaning. That's the personal way and that's the first way.

The second way is that we can give meaning to life in a scientific sense,

where we actually say, `The meaning of life is,' and I've tried to do this in

many of my books such as "The Selfish Gene," "The Blind Watchmaker." The

meaning of life is how we understand, how we interpret the existence of life.

It's due to evolution, it's due to natural selection. Natural selection

favors certain things and not other things. We develop a deep and satisfying

understanding of the meaning of life in that scientific sense. Similarly,

cosmologists may develop the meaning of their own subject, geologists may

develop a meaning of their own subject. These are very worthwhile and they

give life richness, but I return to my initial point: Even if you are not

satisfied by those things, even if you feel there's got to be some more

detailed meaning, there is absolutely no reason why there should be. The

universe, as I said, does not owe us meaning.

GROSS: As you point out in your book, religion is ubiquitous, so where do you

think it comes from? As you point out in your book, everybody has their

favorite theory about that. What's yours?

GROSS: Yes, it is ubiquitous. At least anthropologically speaking, every

culture seems to have something equivalent to religion. Not every individual

has, and that, I think's, important. So it's not ubiquitous in that sense.

I think it's not that difficult to see why ideas which are appealing are ones

that people hold. Ideas like life after death are very appealing, and it does

seem to be a psychological weakness among humans to believe things that they

would like to be true, even if there's no evidence for them. And quite often

when I'm having discussions or arguments with people, they will say, `Oh, but

I couldn't bear to believe that there's no God,' or `I couldn't bear to

have--life just wouldn't be worth living if there was no life after death' or

something like that, as though that was a reason for believing it. And I

think for them it really is a reason for believing in it. They can't see the

difference between something which you believe because there's evidence for it

and something which you believe because it would be nice if it were true.

Well, unfortunately, there are many things that would be nice but aren't true.

But it does seem to be the case, that the human psychology does suffer from

this weakness, and so that would be one approach to explaining it.

I have various approaches to it. I'm one of those--and there are quite a lot

of people now in biologists--who believe that religion evolved, not because it

had a Darwinian advantage itself but because it is a byproduct of

psychological dispositions which had an advantage. And I suppose this

psychological disposition--one example of that psychological disposition is

the one I just mentioned, which is the disposition to believe things because

it would be nice if they were true. That's one of them. Another one, one

that I particularly stressed in my book, is a disposition among children to

believe whatever they're told by their parents or other elders in the tribal

culture. So I think there is a genuinely good Darwinian advantage in children

believing what they're told because life is perilous and human children are

very vulnerable, and by far the best way for a child to decide what's the best

thing to do under many circumstances is to listen to your parents.

So I'm suggesting the natural selection, Darwinian selection, built into child

brains, the rule `believe whatever your parents tell you,' and that's why

children don't jump into fires and don't jump into the sea when they might get

drowned and that kind of thing. You obey your parents. But if you have a

built-in rule that says `Believe your parents, believe whatever your parents

tell you,' that rule has no way of distinguishing good advice, like `Don't

jump in the fire,' from bad advice, like `Do a rain dance in order to make the

rains come.'

GROSS: Richard Dawkins is the author of "The God Delusion." He's a professor

of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Our interview

was recorded last year. We'll hear more of it in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with evolutionary biologist

Richard Dawkins. In his best seller "The God Delusion," he writes about why

he's an atheist and why he thinks science is incompatible with a belief in

God. Dawkins is a professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford

University.

Now, in trying to investigate the probability that a God exists through the

lens that you have, which is evolutionary biology, you say any creative

intelligence of sufficient complexity to design anything comes into existence

only at the end product of an extended process of gradual evolution. In other

words, what you're saying there, if there was a being as intelligent as God,

that God would have had to emerge at the end of evolution, not the very

beginning of it. Would you explain your thinking on that a little bit more?

Mr. DAWKINS: Yes, that's the fundamental consciousness-raising that I think

Darwinian evolution gives us. If it were ever shown that life on this planet

was designed, if somebody came up with unequivocal evidence, say, that

bacterial life was artificially designed on this planet, then I would say,

`How tremendously exciting. Who was the designer? It must have been some

extraterrestrial intelligence, perhaps following Francis Crick's slightly

jokey suggestion of directed panspermia.' He suggested that life might have

been seeded on earth in the nose cone of a rocket sent from a distant

civilization that wanted to spread its form of life around the universe.

The point I'm making is that if there is a designer of life, the very nature

of the argument says that that designer has to be immensely complicated,

immensely intelligent, immensely improbable statistically and, therefore,

cannot just have happened, cannot just suddenly spring into existence de novo.

It must have evolved by the same slow, gradual process as we have seen in life

on this earth. So if life was created on this planet by deliberate design,

then the designer must have evolved somewhere else in the universe as the end

product of--or as a late product of some kind of evolutionary process,

probably a very different kind of evolutionary process, but some kind of

incremental process that moves step by step from simplicity to complexity.

Now, I don't really believe that's happened on this planet. I don't think

Francis Crick did, either. I believe that life did originate on this planet

as a simple beginning by processes that we can--what we shall eventually

understand, lying within the laws of chemistry, which kickstarted the process

of evolution by natural selection, which then went on its upward way by its

slow, steady, incremental process, producing greater complexity, greater

elegance, greater diversity until it culminated in the mammals and birds and

trees and things that we see today.

GROSS: So in that sense, you find the idea of an intelligent god incompatible

with the concept of evolution. No--go ahead.

Mr. DAWKINS: Well, put it this way. At least it's incompatible with the

kind of argument which creationists put forward. The favorite argument of

creationists is, `How could you possibly explain the chance existence of

something like an eye or a brain?' And of course you can't. You have to have

a gradual, slow, incremental process to do it, and by the very same token, God

would have to have the same kind of explanation. You can't use the argument

on the one hand to say, well, `Eyes can't have evolved,' and on the other

hand, use the argument to say God--evade the argument, which will say, `God

can't have just happened.' What I want to say is that God indeed can't have

just happened. If there are gods in the universe, they must be the end

product of slow, incremental processes. If there are beings in the universe

that we would treat as gods if we met them because they very likely may be so

much more advanced than us that we would worship them almost as gods, but they

must have come about by an incremental process, gradually.

GROSS: If you look at like the human sense of morality, can you ask the

question why haven't we evolved more morally as human beings? I mean, we

still have wars and there's still like violence and rape and decapitation and

all of that.

Mr. DAWKINS: Yes.

GROSS: So like--yeah.

Mr. DAWKINS: Well, I mean, I think in a way, the question's the other way

around. If you look at the selfish gene view of life, the question rather is

why are we as moral as we are? And we are actually quite surprisingly moral

compared to what you might naively expect on a Darwinian

nature-red-in-tooth-and-claw view. On a naive Darwinian view, we should

behave morally towards our close relatives--our offspring, our grandchildren,

our cousins and brothers and things--but not towards just anybody. Similarly,

we should behave morally towards other individuals whom we recognize as likely

to encounter us again and again through life who therefore may be in a

position to reciprocate, to pay back the favor.

Now, there are good Darwinian accounts of both those kinds of altruism, which

I suppose is a kind of proto-morality, but we are faced with the problem of

why we are as moral as we are towards nonrelatives and towards perfect

strangers--indeed, members of other species whom we're never going to meet

again and who have no opportunity to reciprocate. And that I think is a kind

of mistaken byproduct--a mistake which I thoroughly approve of, by the way;

it's a blessed mistake. But I think that we are programmed by our Darwinian

past from a time when our ancestors lived in small groups, when every member

of the group in which you lived would have been a clan member, would have been

a cousin of some sort or closer. And every member of every person that you

meet would be a clan member who you would meet again and again and who might

therefore reciprocate. And so the rule of thumb was built into our ancestral

brains, `Be nice to everyone you meet. Behave morally towards everyone you

meet.' Now, that rule of thumb goes on being played out now even though we no

longer live in these small bands.

GROSS: Would you argue that, although religion has been responsible for a lot

of war and persecution, that at the same time religion has been responsible

for a lot of good, for a lot of generous and charitable instincts that have

protected people around the world?

Mr. DAWKINS: Well, yes, it probably is true as a matter of fact that there

have been plenty of good people who are religious. Of course, we all know

them. I mean, some of the nicest people I've ever met have been religious,

and it shines through. So that I don't think is in dispute. What I think's

more interesting is to ask: Is there any general reason why religious faith

should predispose you to be good or bad. If there's a general reason why it

might predispose you to be good, I suppose it might take the form, `God wants

me to be good. I'm fulfilling God's will.' Or, `If I'm bad, God will punish

me,' something like that. And I'm sure there are people who are motivated by

that sort of consideration. I don't think it's a terribly noble reason to be

good. It sort of smacks a little bit of being good only because you're being

watched, because there's a great surveillance camera in the sky watching your

every move and listening to your every thought. I think that somebody who's

good in spite of not believing that he's watched at all, just simply good for

good's sake, that does seem to me to be a rather more noble reason to be good.

GROSS: Richard Dawkins, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. DAWKINS: It's been a great pleasure. Thank you.

GROSS: Richard Dawkins, recorded last year. His book "The God Delusion"

recently came out in paperback. This month he's giving lectures in several

cities around the US.

Coming up, Francis Collins, a geneticist and a former

atheist-turned-evangelical Christian. He finds his belief in God perfectly

compatible with his scientific research. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Renowned geneticist and former atheist Francis Collins

explains his belief in God and why his scientific research deepens

his faith rather than challenges it

TERRY GROSS, host:

When trying to comprehend the universe and our place in it, do you turn to

science, religion, or both? We just heard from Richard Dawkins, an atheist

who finds science incompatible with a belief in God. Francis Collins, a

renowned geneticist, gave up atheism to become an evangelical Christian.

Collins headed the human genome project, which in the year 2000 completed the

mapping of the human genome, the hereditary code of life which includes all

the DNA of our species. He's currently the director of the National Human

Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Earlier in

his career, Collins and his team of researchers identified the genes for

Huntington's disease, cystic fibrosis and a form of adult leukemia. In his

book "The Language of God," Collins explains why he believes in God and why

his scientific research deepens his faith rather than challenges it.

When you look at genetic material and when you were mapping the human genome,

how did you see the intricacy of the genetic material that you were analyzing

as being related to your belief in God?

Mr. FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, whether you're a believer or not, looking at the

intricacy, the complexity of the human genome, our own DNA instruction book,

has to give you a sense of awe. As you page through letters A, C, T and G,

three billion of them, recognizing that this is the instruction book that's

capable somehow of carrying out all of the steps that have to happen for a

human being, from a single-celled embryo to a very complex organism, you can't

help but marvel. For someone who's a believer, as 40 percent of scientists

are, it has an added feature. And that is that you're glimpsing God's

creative genius, and in the process of uncovering this instruction book maybe

you're getting just a hint of what God's mind is all about, which is a pretty

amazing thing to contemplate.

GROSS: When you say that the human genome is our instruction manual, what do

you mean?

Mr. COLLINS: I think it's a pretty good metaphor. DNA is this information

molecule. It's a particularly simple one in a certain way, in that it only

has four letters in its alphabet. They're actually four chemical bases, but

it's the order of those letters, A, C, G and T that carries out all the

instructions that we as human beings and every other organism, too, have to

do. And can be written out in a linear fashion. If you printed it out on

regular font size and regular thickness of paper and piled the pages on top of

each other, it would be as high as the Washington Monument. And you have all

that information inside each cell of your body. So it's a very large book,

but you can think of it as a book, and I think you're probably on the right

track. And a misspelling somewhere in that book could cause you to fall ill

with some problem. And your book and somebody else's book are not going to be

identical, but they're going to be 99.9 percent the same because that's how

similar we humans are to each other. And I guess you could say we're still

beginning readers. We're trying to figure out how to make sense of these 3.1

billion letters in our book in order to begin to apply it more effectively for

medical purposes.

GROSS: You say in your book that a literal reading of Genesis would lead to

the complete collapse of the science of physics, chemistry, cosmology, geology

and biology. What do you mean?

Mr. COLLINS: Well, if you look at the evidence that comes to us from things

like the rate at which galaxies are receding or the radioactive dating of

rocks or the study of DNA and the relatedness of living beings, there is no

way you can backtrack the origins of all this to a period 6,000 years ago,

which is what an absolute, literal reading of Genesis would require. You just

can't tweak around the edges of the consequences of those scientific

investigations to get to 6,000 years instead of 13.7 billion. You just can't

do it.

When it comes to the evangelical Christians, obviously Genesis 1 and 2 is a

serious issue for them. I would just point out the story of creation in the

first two chapters of the Bible is actually two different stories. If you

look at what's in Genesis 1 and then what's in Genesis 2, there are two

descriptions of how humans came to be. And they're not entirely consistent

with each other, which might be a tip-off that one should not assume that

every single word there is intended to be a literal historic description.

GROSS: And Richard Dawkins made the case that science and God are not very

compatible because science is something that is based on empirical evidence.

Science is based on evidence; and religion is based on faith and, for most

people, faith in a supernatural being. So how do you reconcile the

empiricism, the evidence that science requires with the faith and sometimes

supernatural belief of religion?

Mr. COLLINS: Well, a scripture in Hebrews says "Faith is the substance of

things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen." Evidence, interesting,

right there in the definition. I think this is a common misconception, that

faith is something you arrive at purely by emotion and not something where, in

fact, one can assemble evidences that point in the direction of God's

existence and make that more plausible than the denial of his existence. At

least that's what I learned in my 20s. And basically...

GROSS: What evidence would you put in that category?

Mr. COLLINS: I would certainly point to this knowledge of right and wrong

that we humans uniquely have, which asks us to behave in certain ways that

sometimes are an absolute scandal to evolution. Because evolution only cares

about propagating your DNA. What's that all about? It seems like a sign

post. And, of course, the evidence is about the amazing fine tuning of the

universe, which seems to have been put there for some purpose so that we could

exist as beings of complex chemistry. Those seem to be crying out for an

explanation. They're not proofs. Don't get me wrong.

But a scientist who says, well, science is sufficient to disprove God because

we haven't caught him in our microscopes or our other means of measurements,

is committing a logical fallacy. If God has any meaning, God is outside of

nature, at least in part. Science is only really valid in investigating

nature. So science is essentially forced to remain silent on the subject of

whether God exists or not. And that is sometimes forgotten, I think, by the

very strong atheistic viewpoints put forward by some scientists, particularly

those working in the field of evolution.

GROSS: Has mapping the human genome bolstered your view of evolution?

Mr. COLLINS: Absolutely. And this is one of the reasons I wrote this book

called "The Language of God," was to try to put forward what, for me, is a

very comfortable and happy synthesis of being both a believer in God and also

one who studies DNA and sees within it the absolutely incontrovertible

evidence that Darwin's theory of evolution was correct in terms of the common

descent of all living things from a common ancestor.

There's been much disagreement, of course, about this, and great anxieties

have been expended on the question of whether this is a correct theory, and

particularly whether it can be compatible with interpretations of the Bible.

From my perspective, God gave us the ability to look at the details of his

creation. He gave us the ability, with intelligence and with the instruments

that the human mind has managed to put together to read out, not only the

letters of our own DNA booklet, but also that of many other organisms,

including our closest relatives, the chimpanzee.

When you look at that information and you see the precise similarities between

our own DNA and that of other species', and particularly when you look at the

details, not just the general similarity, which might after all be considered

as use of common themes in multiple acts of special creation, you can't help

but come to the conclusion that there is in fact a common ancestor of all

living organisms on this planet, including ourselves. I have no trouble with

that as a believer who also looks to the Bible for answers to important

questions. I don't think Genesis 1 was intended as a scientific textbook. I

think it was intended to teach us something about who God is and who we are in

relationship to him. And just as St. Augustine in 400 AD studying Genesis 1

and 2 was left puzzled about exactly what was being described there, I think

we all, if we're honest, have to be a bit puzzled, too. And, therefore, when

you put together what we see in that description of creation with what God has

given us the chance to learn through science, there's really no conflict. It

was all his plan. He just carried it out using the tools of evolution.

GROSS: Is that what you mean when you use the term "theistic evolution" to

describe your belief?

Mr. COLLINS: Most scientists who are biologists who are also believers have

come to this same kind of synthesis, often without knowing what name to put on

it. I arrived at this same kind of conclusion after becoming a believer in my

20s and trying to figure out how that fit together with the science I was

learning of genetics. It all suddenly made sense. Well, sure, if God had the

intention of creating life, this wonderful diversity of life that we see all

around us on this planet, and ourselves, special creatures with whom he could

have fellowship, in whom he would imbue the soul and the knowledge of good and

evil, and the ability to practice free will, who are we to say that evolution

was a way we wouldn't have chosen. It's an incredibly elegant way to achieve

this.

GROSS: Francis Collins, thank you very much for talking with us.

Mr. COLLINS: It's been a real pleasure talking with you, Terry.

GROSS: Francis Collins headed the human genome project, which mapped the DNA

of our species. His book is called "The Language of God: A Scientist

Presents Evidence for Belief." Our interview was recorded last year. Earlier

in the show we heard from scientist and atheist Richard Dawkins.

You can download a podcast featuring both of these interviews on our Web site,

freshair.npr.org.

Coming up, "Paranoid Park." David Edelstein reviews the new film from director

Gus Van Sant. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: David Edelstein reviews the film "Paranoid Park"

TERRY GROSS, host:

"Paranoid Park" is a new film directed by Gus Van Sant based on a young adult

novel by Blake Nelson. At the Cannes Film Festival last May the jury awarded

Van Sant with a special prize for the film. "Paranoid Park" is set in the

world of teenage skateboarders in Portland, Oregon. Film critic David

Edelstein has this review.

Mr. DAVID EDELSTEIN: Gus Van Sant embodies the notion of the director as

conceptual artist. He regards everything he does as some kind of experiment.

His first film, "Mala Noche," was a tale of romantic obsession that played

like an expressionist fever dream. Then came "Drugstore Cowboy," outrageous

in its premise, the addict as Western outlaw, but conventional in technique.

Then "My Own Private Idaho," conventional in its theme of teen alienation but

outrageous in technique, a mix of Shakespeare, surrealism and urban grit.

When Van Sant made formula studio pictures like "Good Will Hunting," he told

interviewers he was working in the tradition of Renaissance artists who

strived to suppress their personal voices. I'm not kidding. A remake of

Hitchcock's "Psycho" posed the question: If you replicate a film shot by

shot, what will you wind up with? It turns out, nothing pretty.

"Paranoid Park" belongs in the series that began with Van Sant's "Gerry" and

continued with "Elephant" and "The Last Days," trance-like works in which you

drifted through time and space with nonactors, or actors behaving like

nonactors. This is the best of those free-form works, a supernaturally

perfect fusion of his art project head-trip aesthetic and Blake Nelson's

finely tuned first-person young adult novel. The protagonist and narrator,

Alex, played by Gabe Nevins, is a Portland, Oregon, teen whose father has

moved out and who gravitates toward a grotty skate park for what he calls, in

voiceover, "thrown-away kids." One day Alex gets called to the school office

where a detective, played by Dan Liu, asks about a grisly death near Paranoid

Park.

(Soundbite of "Paranoid Park")

Mr. DAN LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Let me tell you what my situation is.

I have this security guard and we find him deceased on the railroad tracks and

so we're thinking maybe he tripped or he fell, but the autopsy says he was

struck by an object. And we also have a witness that says he saw somebody

throw something over the bridge into the river. We happen to have that

object, and it's a skateboard. Now, the funny thing is there's some DNA

evidence on the skateboard that puts it at the scene of the crime.

Now, where did you go?

Mr. GABE NEVINS: (As Alex) I drove around downtown a little to Subway and

got something to eat.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) OK. There's about 1,002 subways. Which

one did you go to?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) By the waterfront.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) OK. And the one over in the World Trade

Center? That one?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Yes.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) K. What'd you get?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Turkey and ham on Italian herb and cheese bread,

toasted, tomato, lettuce, pickle, olive, mustard, oil and vinegar...

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Did you get mayo?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) No.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Got to have mayo with that.

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Mayo's sick.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Mayo's sick? What kind of bread was it?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Italian herbs and cheese.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) And you have a receipt in your pocket for

that?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) No. I don't keep Subway receipts.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) OK. How much did it cost then?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Like six-something. Subway's expensive.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Six-inch? Twelve-inch?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Six.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Six-inch for six bucks. So you must have

got the meal, then, right?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Nah, I just got a drink.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) OK. All right.

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Large Dr. Pepper.

Mr. LIU: (As Detective Richard Lu) Who'd you eat with?

Mr. NEVINS: (As Alex) Myself.

(End of soundbite)

Mr. EDELSTEIN: Based on his sandwich description, I'd believe Alex, but it

turns out via flashback that he was at the scene of the death, although guilt

or innocence are inadequate to describe what he did. Although he longs to

tell someone--his father, who seems oblivious to his needs, or even that

detective--he pulls into himself.

Nelson's book is linear, and even invokes Dostoevsky since Alex is reading

"Notes from Underground." Van Sant dumps Dostoevsky and ruptures the narrative

line to drive home Alex's inability to get at his own mixed-up feelings. The

director, and cinematographer Christopher Doyle, leap from the static and

realistic to the dreamlike and woozy with super-eight skateboard footage that

seems to bubble up from the collective unconscious of the misfits of Paranoid

Park. The soundtrack is a vivid mash-up--Beethoven, country, the melancholy

Elliott Smith capped with Nino Rota's carnival-esque Fellini music, which

drowns out Alex's cheerleader girlfriend.

Van Sant found his leading actor from a casting notice on MySpace, and Nevins

has a good soft face, a seven-year-old's head on a 17-year-old's body. There

are times when his inexpressiveness is a little too inexpressive, but the

voiceover narration keeps the movie grounded, and Alex's tumultuous emotions

are right there in the film's look and sound. In life, when you look at a

teenage boy with no expression, his clothes drooping, his long hair in his

eyes, perhaps toting a skateboard, you might construe his blank affect as a

sign of the blankness within. But in Van Sant's hands, that supposed void

turns out to be not too empty, but too full. "Paranoid Park" is a trip into

space--not outer, but inner--in ways that movies rarely are. This time the

experiment is a raging success.

GROSS: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine. "Paranoid Park"

opens today in New York and LA, and can also be seen in the pay-per-view

section of many cable systems as part of the series called IFC in theaters.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.