'The Watchers' Have Had Their Eyes On Us For Years

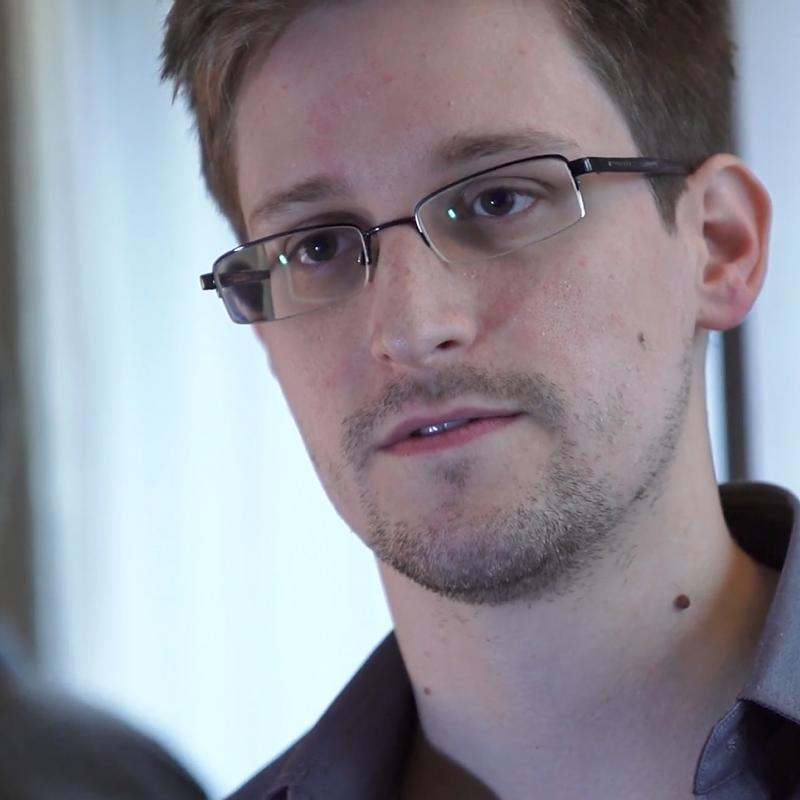

Shane Harris, an author and journalist who covers intelligence, surveillance and cybersecurity for a number of publications, says that the revelations about the NSA from Edward Snowden are nothing new, and that such programs have a significant recent history in the United States.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on June 19, 2013

Transcript

June 19, 2013

Guest: Shane Harris

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. As shocked as you may have been to learn about the secret National Security Agency programs leaked by Edward Snowden earlier this month, you may also be surprised to learn about some of the surveillance programs that were their forerunners.

My guest, Shane Harris, wrote about those programs and their architects in his book "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State." He just joined the staff of Foreign Policy magazine, where he's covering intelligence, surveillance and cybersecurity. He'd been writing about the newly revealed NSA programs for the Washingtonian magazine.

Both of those leaked programs were created to help track terrorists and their co-conspirators. The secret program, known as PRISM, allows the NSA to tap directly into the central servers of nine Internet companies - including Microsoft, Apple, Google and Facebook - enabling the agency to collect material such as email messages, file transfers, audio and video files, and search histories. The other leaked program collects metadata from phone companies. Metadata isn't the content of calls; it's phone numbers and numbers called by those numbers.

Shane Harris, welcome to FRESH AIR. You know a lot about the history leading up to where we are now. Before we get into some of that history, I'm wondering if, knowing what you know, you were surprised or not when Edward Snowden revealed these secret surveillance programs.

SHANE HARRIS: I wasn't terribly surprised. It's always interesting to get more details, and as a reporter you're always looking for things like code names and for what the legal authorities are underpinning something. But I wasn't surprised. I mean, fundamentally, what he's describing as this vast surveillance architecture that is chiefly run by the National Security Agency, is what I wrote about in my book.

And it's something that, you know, did not start just after 9/11, either. There is a decades-long history to this, up to the rise of surveillance in America. You know, what was sort of - I guess, stunning to me was just the breadth of it. I mean, I knew that this was broad, and this was a very sort of - you know, pervasive surveillance architecture. But whenever you still get individual details like the court order that Snowden leaked, ordering Verizon to hand over records of every phone call on the network, that still is sort of stunning, but it's not surprising.

GROSS: One of the things you write about in your book is how the dawn of the digital era - you know, digital phone calls, cellphones - was a real crisis for the American surveillance system. Compare for us what surveillance did in the old phone era, as opposed to what it can and can't do now technologically, with digital phones.

HARRIS: So there used to be a time that if an FBI agent, say, wanted to conduct a wiretap, he would literally go down to the phone-switching station and take a pair of alligator clips and clip on to a lug nut with a copper wire attached to it that ran to a phone line, and that's where wiretapping came from. You would literally tap the wire.

And there was a great certainty in that analog system that you knew that the number that you were, as they say, going up on, was connected to a certain phone at a certain place, and you probably had a pretty good idea whether or not it was a U.S. citizen attached to the other end of that phone.

What happened in the digital transformation was that all of that analog technology and all of the certainty of those wires running through the ground became this vast system of ones and zeros and digital infrastructure in which everyone's communications were all mixed up together, and it was very difficult, technologically speaking, to know with certainty that the number that you were going in to tap was connected at the place that you thought it was.

So around about the early to mid-1990s, as this transition happens, the FBI and the National Security Agency start to fear that they're going to be essentially put out of the wiretapping business because the telephone system was not built at that time to let these agencies go in and quickly tap into the infrastructure and listen to the phone call and get the information that they wanted.

So they had to go to these companies and eventually had to enact - Congress had to enact the law that said you have to build this digital technology, which we all agree is great and holds great potential for commerce and communications. We're not trying to stymie that, but you've got to build it in such a way that we can get into it if we need to with a lawful order, with a court - with a warrant.

And then what happened is that as all these communications proliferate, the NSA also looks at this and says, OK, well, wait a second. Now that we can - if we can master the universe of how to go into this infrastructure, we can effectively have access to communications all around the planet.

It used to be in the early days of the NSA that the way that they actually obtained signals intelligence, as they call it, was by either boring into undersea cables or building these massive satellite dishes that had to snatch radio frequencies and transmissions as they went through the air. Now they're realizing if we can get into this digital network, and as they used to say in the late '90s, they would say to some policy documents, live on the network, they would effectively be able to monitor global communications.

And what's more, because all of this communication was transiting through lines inside the United States, and the United States was sort of the central switching station for the global communications grid, NSA could effectively tap global communications inside the United States without ever having to leave home.

They were aware of this in the mid- to late 1990s, but the law at the time really forbid a lot of that kind of intelligence gathering in the U.S. 9/11 changed all that. The laws were changed. There was a real cultural shift in the agency towards doing that kind of work in the United States.

Let's back up a little bit before we get to 9/11. Let's go back to the mid-'90s, when the FBI and the Justice Department wanted to make sure that telephone companies built their networks in a way that they could be tapped. So what were the phone networks required legally to do?

At the time, they were required, whenever an agent, a law enforcement agent, showed up with a warrant to essentially serve the warrant but to give the information that they were looking for, so let the agent go in or have a representative from the phone company go in and do the wiretap. The law changed such that in the future, whenever the companies built and installed these digital network systems for communications, they too had to be built in a way that law enforcement could execute a warrant quickly and easily.

So there was this sort of problem that was happening before this transition happened where, you know, you would take, you know, for instance a phone-switching station where ordinarily an FBI agent would show up, execute the warrant, everybody's happy. As this transition to digital was happening, there were literally so few digital ports at which you could plug in the equipment to do a wiretap that there was a backlog of requests happening from the government.

So these phone systems were turning digital, but they weren't quickly evolving to have the tapping technology built into them, as well. So the phone companies are building these modern systems, but they're still relying on this sort of antiquated way of tapping information. So they basically had to install and build in an architecture that allows for digital surveillance at a high volume and to do that for any number of orders that the government might have to issue on that day.

So essentially what you have now is a phone system that can be easily tapped and quickly tapped the way it could back when it was analog, but there was this transition period where it was not at all clear that the companies were willing to pay for the technology upgrades and the changes to their systems that they would have to do in order to make this stuff tappable.

And there was a real debate about not just who was going to foot the bill for that but about whether this would give the government even more intrusive access into communications because you can just swallow up so many more kinds of digital communication at once, rather than tapping one phone line at a time.

So this was really part of the context and the texture of that debate, and the compromise that they ultimately reached was that, OK, we the telephone companies will build this stuff in a way that you can tap it, but you've always got to come to us with a warrant and spell out exactly what it is that you're looking for. You can't just go into the system and plug in and fish around until you find something. You have to be able to specifically say what it is that you want to search.

GROSS: So let's jump ahead from the mid-'90s to the late '90s, just as an example of what was being done and how in this example it failed. And I'm thinking of Able Danger, which you write about in your book. And what was the goal of this program?

HARRIS: So Able Danger was a program run by the Army out of a small group located in suburban Virginia on an Army base. And the idea here was that this very innovative band of sort of techno-geek/soldiers got this notion that they could use the burgeoning power of the Internet and of then very primitive by our standards today data mining and search technology to go out on the Web looking for clues about terrorism.

And what they wanted to do was go out and sort of search for key words about things like, you know, bin Laden and al-Qaida and other terrorist groups, which were pretty much off the radar for most people back then but were known to people in the intelligence community, and see what they could find in this sort of big, vast public record. We would know this today as Googling.

(LAUGHTER)

HARRIS: They were effectively Googling about terrorism. But at the time, the technologies that they were using, which you would recognize today as something on your phone or on your computer, were really cutting-edge, you know, searching technologies. And the Internet at the time was, you know, probably even more of sort of a Wild West than maybe it is today, but people in the intelligence community did not necessarily regard the Internet as a source for authoritative information.

So this group got the idea that if they could go out and sort of, you know, mine the available data, what could they see. And it turns out that they found a lot of connections. You know, and you know this today. You could spend 30 minutes Googling someone and probably come up with a lot of information about them, and it might look pretty persuasive and rather compelling.

Well, the analysts who were running this program Able Danger took all of that information and brought it in and put it in a government database so that they could then, at their leisure, sort of go through and pick it apart and look at it and see what was in it. Well, just in the course of going out and searching for a name like bin Laden or even something as broad as terrorism, you're going to hit on, as they did, Web pages and chat rooms that also contain the names just in passing of U.S. persons or of even prominent Americans.

All that data then got ingested into the system, and when the Army lawyers found out about this, they said, well, wait a second. Why are you going out and conducting searches that are pulling in the names of Americans, including even some American politicians? And why are those names ending up in a government database?

And these techie guys tried to explain no, no, it's not - we're not spying on them, it's we're looking for this other information, and this is just sort of incidental collection. Well, the Army lawyers didn't see it this way. They looked at this, and this is pre-9/11, remember, and said you are effectively conducted a domestic intelligence operation on U.S. persons. You have got to shut this down and destroy everything that you have collected.

And this was really a pity to the people who were doing Able Danger because they believed that they were actually coming up with useful information that importantly showed a network of terrorists, possibly connected to al-Qaida, that were operating inside the United States.

When that information came out years later, it looked like this small group of Army analysts had possibly figured out that there was a plot in the offing and that they may have even had the first strands of the 9/11 plot in this government database that was destroyed because the privacy regulations and the rules at the time were so strict that even the incidental collection of an American effectively meant that you had to shut the entire system down.

GROSS: So they had to delete everything that they'd collected.

HARRIS: Everything. In fact in my book I interviewed the person who was the lead analyst on this, and he described having - the day that he had to do it, having to sit at his computer and literally hovering with his cursor over these, you know, Microsoft files that they had created in their computer and just hitting delete, delete, delete, delete, and everything was gone.

And they truly believed that they were on to something there and that had they been allowed to continue investigating it, they might have found information that they could have then passed off to the FBI that said hey, we're coming up with these weird hits. We don't exactly know what they mean, but it looks like there's some sort of network that is taking root in the U.S., we should go investigate this. And that just never happened.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Shane Harris, and he writes about intelligence, surveillance and cybersecurity for Foreign Policy magazine, where he's a senior writer. He's also the author of the book "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State." Let's take a short break, then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Shane Harris, and he writes about intelligence, surveillance and cybersecurity for Foreign Policy magazine, where he's a senior writer. Let's jump ahead to after 9/11. Under the Bush administration, John Poindexter, who had become something of a household name because of his participation in the Iran-Contra scandal, he created a program called TIA, Total Information Awareness. He wanted to gather and analyze data in a way that had never been done before. What was his goal?

HARRIS: So his goal was to create a system that could access all of the digital information anywhere in real time, everything from phone calls and emails, text messages, rental car reservations, credit card transactions, prescription records, you name it. If it leaves an electronic signature, it was fair game.

And the idea behind TIA was that it would go out and look through this huge, this universe of data and look for patterns of activity or patterns of transactions that analysts had predetermined were associated with terrorist attacks. So it would go out looking for things like, hypothetically, somebody buying one-way plane tickets, staying at a hotel in a certain city who had also bought, you know, photographic surveillance equipment and who maybe had some sort of connection through his phone records to an overseas number in Pakistan. And it might say that looks like somebody who might be an agent who is here doing surveillance of a target. It also might not be. It might be completely innocuous, and in all chances it probably would be, but his idea was that he would build this system that would say look, we have this vast universe of data. Any movement that you make today leaves a digital signature, a digital trail.

Investigators after a terrorist attack has occurred go back and use all of those digital signatures and trails to figure out who these people were and how they did the plot. Why can't we look at it before the event occurs and try to predict with some degree of certainty where we should then be focusing our attention and which people we should be more closely monitoring? But to do that, you had to collect all of the information available everywhere.

GROSS: Why was this program shut down?

HARRIS: For a number of reasons. One was that what he was proposing at the time, and this is before we realized what had been going on in secret at the NSA, sounded Orwellian. I mean, it sounded just almost absurd. The idea that you would want to go out and give the government access to truly every single person's record and let them root through it really seemed like just a step too far even, you know, in the, you know, one or two years after 9/11, when the country was still very much on edge, and we were, you know, fighting a war in Afghanistan.

It just seemed like it was just excessive. The name creeped people out. It was called Total Information Awareness. It had this logo of the pyramid from the great seal of the United States with this floating eye on it that was casting this beam over the globe. It looked very menacing. And it did not help at all that the guy running it was John Poindexter, who was best known as the key architect of the Iran-Contra affair.

It just had all of these negatives going against it, and John Poindexter, for as brilliant of a technologist as he is, was never really much of a public relations manager or a politician. And it was also a very public effort, and people looked at this - there was no secrecy to it. It was all out in the open. And people looked at this and said this is exactly the kind of surveillance excess that we've been warning about since 9/11. This is the government going way too far and being way too intrusive into people's private lives, and they shouldn't be allowed to collect this kind of information. So shut the program down.

GROSS: So the program shut down, but then it kind of lives underground?

HARRIS: Correct. So behind closed doors, the people who were in charge of TIA and others in the intelligence committees in Congress struck a deal that TIA would be as they say defunded from the Defense budget but that all the money for it would be moved over to the classified side of the budget, the black budget as it's often called.

And it was disbanded in name, and all of the various components of the research program were separated, were given new cover names, and almost all of them were then shifted over to the management and control of the National Security Agency, which unbeknownst to everyone in America, most people in America at the time, had been running its own total information awareness program and so was very interested in what Poindexter was doing.

Their officials had met with Poindexter. They'd even experimented with some of his technologies. So TIA is shut down publicly, and privacy advocates really declared a great victory for this, but unbeknownst to them, the work just continued in secret at the NSA and became part of this larger, vast surveillance apparatus that we're learning more about now.

GROSS: At the time, Michael Hayden was the head of the NSA, and I think the program that you're referring to that the NSA was already running that was similar to TIA was called Stellar Wind. So what was Stellar Wind doing, and how was that changed when TIA was kind of folded into it?

HARRIS: So Stellar Wind is a cover name that's given to a variety of different intelligence collection programs that President Bush authorized under his own authority after 9/11. And what this was doing is they were looking, they were intercepting phone calls inside the United States that they had reason to believe were connected to terrorism.

What's often referred to as the warrantless wiretapping program falls under this umbrella. They were also looking at email communications. They were also looking at things like metadata, some of the things that we're talking about now. It was very similar to TIA in the concept that if you could get access to this vast universe of information that there was a lot that you could find about potential plots and potential bad actors and terrorists.

One of the key differences, though, and I should emphasize that TIA was never actually a real working program, it was always research, it was never operational, but what happened under Stellar Wind was very different in that it did not have a really robust set of privacy controls.

And what we mean by that is that there wasn't as much caution taken to insuring that the communications of innocent people were not swept up in this vast sort of vacuuming up of information. There was a lot of collecting that was done without warrants. There was a lot of listening to phone calls and reading of emails that was done without oversight of a court.

And in that sense it was different from TIA in that what Poindexter wanted to do was sort of re-imagine privacy controls. He wanted to have this very strict architecture whereby all of the data was anonymous and that only the computer would know who the real people underneath it were and that you would have to go get a court order to see who those identifying pieces of information.

So it almost - you know, Stellar Wind, I like to think of it, was sort of like TIA but let off the leash.

GROSS: So is that program still operational?

HARRIS: Effectively it is in the sense that the NSA is doing many of the same kinds of intelligence collection and analysis that they were doing under Stellar Wind, except now it's all covered by law. I mean the term Stellar Wind is no longer used, but all of these sort of, you know, these programs that are all about collecting the data and storing it and analyzing it, that's very much what Edward Snowden has been describing and what we've been talking about now the past couple of weeks. It's just that now it is all much more clearly legal than it was after 9/11 and in the few years after the attacks.

GROSS: Shane Harris will be back in the second half of the show. He's the author of "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State," and is a senior writer for Foreign Policy magazine. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Shane Harris. We're talking about the two leaked surveillance programs, and the surveillance and legal history leading up to them. Harris is the author of "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State." He just became a senior writer for Foreign Policy magazine, where he covers intelligence, surveillance and cyber security.

Foreign intelligence surveillance is regulated by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act - FISA - which was signed into law in 1978. The act created a court - the FISA court - which approves surveillance search warrants.

So in 2008, the FISA Act - the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act - was amended. Will you explain how it was amended?

HARRIS: Right. The important change was that it now allows the government to essentially go to the FISA court asking for broad authority to monitor a whole set of electronic information. It used to be that you went to the FISA court and said we have this particular individual or this phone number that we want to monitor. Now they can go to the court and they can say we want to gather up information on the following list of emails or people in the following region. The key requirement here is that it cannot directly target. If you're doing a broad surveillance, it cannot target - is the terminology - a U.S. person. So you can go out looking for foreign information and you don't need particularized warrants to do that.

In the process of doing that, it's almost inevitable, however, that you will collect data on American citizens and legal residents, and then you have to filter all of that out from the foreign data.

GROSS: So in 2008, the government's access to information was broadened?

HARRIS: That's right. Effectively, they could now go to the court and say we want to collect on this whole range of information as long as it's about foreigners - whereas before they would have had to go to court to get authority to monitor an individual U.S. person or an individual phone number. So it really did broaden this authority, and to a certain degree I think it probably lessened court oversight because the court now approves these authorities that last for a period of at least a year. And as the authority is granted, then the government can keep sort of adding new targets onto the list if they want to. So it's almost like they're approving the methods or the program of surveillance more than they are the individual particular surveillance that's being done.

GROSS: What was the debate like in Congress over the 2008 FISA Amendment Act?

HARRIS: It was significant. I mean there was a lot, it broke down largely on partisan lines - with I think, with Republicans favoring changing the law and Democrats largely being opposed to it because they saw it as the Bush administration wanting to enshrine and protect in law the kinds of things that it was doing possibly outside the law, and it really got really quite heated. And a lot of the context for this was if we don't change this law, we are going to tie the intelligence community's hands behind its back. They won't be able to, for instance, monitor purely foreign communications as they just happen to move across infrastructure that's based in the United States. And the U.S. is sort of the central terminal for a lot of foreign information; it just moves over our cables. So there was a real sense of urgency towards changing that law and the debate got very, very heated and highly partisan.

GROSS: And is it easy for Congress to make that debate public - in other words to take their concerns to American citizens when the legislation has to do with classified programs that the people in Congress can't really discuss with the American public?

HARRIS: It's not easy. You know, so Senators Wyden and Udall have been saying for more than a year now that there is a provision in the Patriot Act that's being interpreted in a way that most Americans might find shocking - that it's allowing the kind of surveillance and collection that the Patriot Act was not designed to allow. We now believe that that is the metadata collection that we've been talking about. So it's very difficult because, you know, they are - you know, there are members of Congress, in many cases their staff don't know about these programs or very few of them do. If they want to read about them they have to go into a closed room and taken hour or two to read up on this stuff. Many of them, I'm sure, are voting for legislation that they have not fully read and don't completely understand. So it is, it's extremely difficult to have a debate when they are bound, really, by their oath and by their law from talking about all the details that they may know.

GROSS: So when the government requires a warrant to get specific content from a phone call, it needs to get the warrant from the FISA court. So how does the court operate? Because from what I've read, just about all the requests are granted.

HARRIS: That's right. Nearly all of the requests are granted. What happens is that a representative from the government - usually from the Justice Department - goes before the court with essentially a form saying this is the information that we're seeking. If it pertains to a U.S. person, they want to record the phone call, has to say who the person is or at least give some, you know, indication that it's a U.S. person or that they know that, or they can go seeking more broad authority to collect foreign information, like many, many email addresses, for instance. The judge looks at that and the judges are all currently sitting trial judges. They do this assignment for a brief period - well, not a brief period - for a number of years, but they rotate in and out, looks at it, says does it comport with the law as it's written, and if so, they approve it, and the warrant is granted and the search is conducted.

GROSS: So who appoints the judges?

HARRIS: The chief justice of the Supreme Court appoints them. There are 11 members on the panel and each serve for seven years and they have day jobs. They are judges in other federal courts and they do this on a case - on a as-needed basis.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Shane Harris, and he writes about intelligence, surveillance and cyber security for Foreign Policy magazine, where he is a senior writer. He's also the author of the book "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State."

Let's take a short break, then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Shane Harris, and he covers intelligence, surveillance and cyber security for Foreign Policy magazine, where he's a senior writer. He's also the author of the book "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State."

So Ed Snowden, who leaked the two surveillance programs that everybody's talking about now, leaked it in his capacity as working as a private contractor for a private intelligence company. He had worked for the CIA earlier in his career. But right - when he downloaded all this information and put it on a thumb drive or something, so that he could leak it, he was a private - working for a private contractor. That seems to be a game changer in some ways, you know, the number of people who are working in the intelligence system in the United States who are working for private companies, as opposed to for the government. Are private contractors vetted any differently than, for instance, somebody who was given top-secret information - access to top-secret information and is working for the NSA?

HARRIS: Well, they're not supposed to be. I mean if you have access to a particular piece of information, the higher up the chain of secrecy that it goes, theoretically you are vetting should have been just as rigorous as if you were a government employee as opposed to a contractor, which is what Ed Snowden was.

What I'm surprised by is how it is that any employee at his level - whether it was a contractor or not - would have access to some of the information that he had access to. You know, the NSA is, prides itself on being probably one of the most secure agencies in government. This is the agency that after all specializes in cryptology, you know, they are cod makers and they are code breakers. So how is it that these incredibly sensitive documents, particularly the court order related to metadata, was just accessible to anyone to remove with a thumb drive, regardless of whether they were a contractor or not? But it does raise this question about what are the contractors themselves doing on the front end to vet the kind of people that they're bringing into this system.

It's also worth noting too that the process of getting a security clearance has its own issues and its own problems. A lot of the background checks are actually outsourced to other contractors. That said, you know, it is impossible to screen out entirely for anyone who is going to take it upon himself for whatever reasons, political or financial or whatever they may be, to violate his secrecy code. You know, in Snowden's case he's saying he felt very moved philosophically and politically to do this. It's difficult to screen that kind of person out in the security clearance process, particularly when, you know, these agencies just need so many thousands of people to keep the system running.

GROSS: I read that Snowden had a sticker - has a sticker - on his laptop that says: I Support Online Rights. Electronic Frontier Foundation. And the Electronic Frontier Foundation is a foundation that has been very active in freedom of speech on the Internet, protecting that and trying to prevent any kind of invasion of privacy on the Internet. But, you know, somebody who I was reading made the point, and I think this is an interesting point, and I'd love to hear your reaction to it, that a lot of the people who are very technically savvy about the Internet kind of came of age with the ethic that like information is free and the Internet is open, you know, which is, you know, a beautiful ideal but that kind of idea goes really counter to the whole idea of the kind of secrecy and secretly getting access to information that spy agencies do - that is what they do.

HARRIS: I think that's right. I mean there really is an almost cultural collision - a clash that's going on here where you have these organizations that are built on compartmentalization and secrecy and deceit to a certain degree needing the expertise of people like Ed Snowden, who grew up in the digital age, who grew up using computers and the Internet as if they were regular household items. That's the workforce that the NSA has to pull from. The value systems may not be compatible, however. You know, it strikes me that, you know, there are a lot of people, though, who probably work for the NSA who may be do feel the way that Snowden did, who believe in this idea of freedom of information. I've known many people who've worked for these agencies who would consider themselves civil libertarians and to have a very strong view of privacy. But you know, you make a commitment when you go to work for one of these agencies to keep the secrets and to almost sort of push your own beliefs to the side. You know, in his case I think he felt like his own beliefs overwhelmed his commitment to secrecy.

But I think you're likely to see this kind of thing happen again. The NSA cannot afford to say, you know, we won't hire anybody under the age of 35. Or we won't hire anybody who has expressed an interest in digital privacy rights. I mean to that point, actually, Keith Alexander, who is the director of the NSA, about a year or so ago actually went out to Las Vegas to one of the more famous hacker conferences, he shed his uniform, he put on a pair of jeans and a T-shirt, and he gave the keynote address to this audience of self-professed computer hackers who are the kinds of people that NSA might on another given day regard as threats, and said we need your expertise, we need you to come work for us, you know, we need to do more work securing the nation's cyber networks and preventing espionage from foreign governments, and you all know how to do that. So they seem to, you know, they're taking a risk perhaps by bringing in people who don't necessarily see the world of information the way they do and who have a more sort of liberal view of it, if you like. At the same time, they can't afford not to hire these people because those are the experts.

GROSS: And talking about how private contractors who are dealing with intelligence and who are working for the NSA has kind of changed the story. I want to ask you about Mike McConnell. He's the former head of the NSA and he's now one of the people at the top of Booz Allen, the private intelligence company that Ed Snowden worked for. And one of the things McConnell has been doing apparently is consulting to the UAE - the United Arab Emirates - and helping them use data mining and metadata. So I'd like for you to talk a little bit about how private contractors are learning so much about metadata from working with the NSA and then maybe taking that knowledge to other countries.

HARRIS: Well, McConnell - Mike O'Connell is a great example of this because he's somebody who, you know, he started his career in the military, he became the director of the NSA, and he was actually running the NSA at this time that it was having to deal with this explosion in digital technology. So McConnell will sort of getting a front row seat to the kinds of, you know, the information world, if you like, that we are dealing with today. And he was pretty ahead of his time on this and recognized that NSA had to evolve and get more technologically sophisticated. And he left government and went to work for Booz Allen, where he did very well and really took that expertise that he learned in that first time in government to build its private intelligence business using his contacts and his knowledge of the problems that the government deals with and the kind of intelligence challenges that these agencies have.

GROSS: After 9/11, of course, he's more in demand than ever. He's brought back to government in the second term of the Bush administration as the director of National Intelligence. By the time that he came back, the sort of partnerships between these intelligence contractors and the government had been tighter than ever. I mean it was definitely at that point the case that the intelligence workforce, you could almost not even separate it into contractor and government employee anymore, there were just so many from each sides working together, and the government had become almost entirely dependent on that outside workforce and the expertise that they brought in. And remember, you know, the real technological innovators and the people who really have grown up with this information, and you know, who have sort of, you know, the best ideas on how to build technology, frequently don't come from inside the government, they come from the private sector.

HARRIS: So McConnell in coming back to government the second time is really again getting a front row seat to how this information revolution that he had sort of been there for the beginning of it is now exploding. And now it's, you know, it's metadata everywhere. It's the NSA having to collect on all of these targets and do it inside the United States.

HARRIS: And he actually was - played a key role in helping to change the surveillance law to allow all of this kind of collection that we're talking about today to put it more firmly on a legal basis. So all that information that he absorbs about how the government does this kind of surveillance, how it collects this data, what it's useful for, what its limitations are, the kinds of problems you're going to run into with privacy law, he can take all of that now back to the private sector and go to a place like the UAE and say, look, I've effectively helped build these systems. You know, this is how we did it in the United States. This is how you can do it here. And Booz Allen can do that for you because, you know, in effect a lot of their people helped build it for the NSA or helped run it for the NSA as well.

So there's kind of this symbiotic relationship now where, you know, the knowledge and expertise that you gain in the public sector can then go right back out and feed the private sector. And in McConnell's, you know, case, you can come back into public sector and then rotate back out again. And I think that is sort of just the new reality of how the intelligence business is run in this country. I mean it's operational and it's secret but it's also a very big business.

GROSS: I'm wondering if you think that we might have the kind of intelligence blowback that we've had already with weapons. You know, like we've sold weapons to the Afghan resistance fighting the Soviets in the '80s after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. And then the weapons that we had sold them to get the Russians out were then turned against the United States after 9/11. Do you think the same might happen with intelligence, that like we - private contractors help companies - that private contractors help countries, countries that maybe now are our allies, set up, you know, metadata collecting surveillance systems and then they end up being used against us.

HARRIS: Sure. I mean there's also the possibility that they could be, you know, these systems could be bought and purchased by repressive regimes who don't have the same respect for free speech and privacy rights that we do and that these technologies that were built to monitor communications in America are then used to suppress political speech in other countries. And there's evidence that that's happening too.

And the surveillance business does not limit itself to only selling to the U.S. government. I mean it's a global business. And how these - the technology itself is agnostic. It's all about how it's used. So if we want to employ it in a way that we think is respectful of the First and Fourth Amendment and privacy rights and all that, there's no guarantee whatsoever that a government someplace else might do that the same.

And that expertise that you develop as an intelligence contractor working for the government, you could then certainly go and use that expertise to sell it someplace else and to build a system for another country that doesn't respect privacy the way we do. You know, another way that this also manifests too is in the creation of computer viruses.

I mean, you know, the United States is in the business of cyber warfare now. We are building worms and viruses and exploits that are meant to go out and spy on other countries and damage infrastructure. When those things and that expertise gets out into the wild too, that is something that can be sold on an open market as well. We don't have an exclusive domain over this knowledge and this technology.

GROSS: I think one of the questions a lot of Americans have is this. Even if the government now has the best of intentions in collecting this information and plans to use it only in instances where it thinks terrorism can be thwarted, if the government has this information, can't the leadership change its mind and start secretly using this information for illicit purposes and to spy on Americans, to spy on dissident Americans?

HARRIS: Yes, that is the great fear in all of this, is that the government is building a capability that even though it insists right is being used for lawful and narrow purposes, that in a different political environment or a different security environment, that that system could be relatively easily and quickly switched to target all kinds of other activity.

Now, you'll often hear this referred to in the intelligence community as mission creep. A system or a program that was set up for one purpose starts, you know, kind of growing tentacles and being used for other purposes as well. And I think the reason that that in this instance is actually a well founded concern is that the intelligence laws that we're talking about today that were put in place to govern this activity were set up in the late 1970s specifically because of abuses by the intelligence agencies, because they were spying on political dissidents, because in one instance they were tapping the phones of a Supreme Court justice. So these laws were put in place to prevent a certain kind of activity, and just because the programs are now being used only for counterterrorism doesn't mean that they couldn't be used for that other kind of bad activity if the circumstances change.

And that really has always been the reason we have these laws and the reason that why, when we hear about this vast collection of data, that there is reason to be concerned and to want more answers from the government about, well, specifically how are you using this and what assurances can you give us that you're not going to be using it for something like in the bad old days?

GROSS: Well, Shane Harris, I want to thank you so much for talking with us. I know you're writing a book on cyber war and cyber security. I look forward to reading that when it's completed.

HARRIS: Thanks for having me. It was my pleasure.

GROSS: Shane Harris is a senior writer for Foreign Policy magazine and is the author of "The Watchers: The Rise of America's Surveillance State." You can read an excerpt on our website, freshair.npr.org.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: The Museum of Modern Art has a new exhibit of major early works by the pop artist Claes Oldenburg. Our classical music critic Lloyd Schwartz went to see it and loved it.

LLOYD SCHWARTZ, BYLINE: The sculptor Claes Oldenburg was born in Stockholm but grew up in Chicago, went to Yale and came to New York in 1956, where he became a key player in the pop art movement which was the major counter-reaction to the abstract expressionism that dominated the 1950s.

So much for art history. Although Oldenburg is a serious artist, probably no artist in history ever created works that were more fun. In a new show at the Museum of Modern Art - really two shows - practically everyone, including myself, was walking through the galleries with huge grins on our faces. Though some of the images are unsettling. In the first and scarier part of the exhibit, the objects are from Oldenburg's 1960 shows called "The Street," images inspired by his living on New York's Lower East Side. These are figures and objects, many of them suspended from the ceiling, made out of cardboard and burlap, nightmarish but also childlike, brown with black edges as if they were charred.

There's a wall tag for a piece called "Fire From a Window" that took me a while to find, because it's a small board sticking out from the edge of a wall high up above the gallery - like a flame leaping out of a building. The second and larger part of the exhibit is called "The Store," and these include some of Oldenburg's most iconic images from the early '60s. And here's where the smiles begin to widen.

The objects are mostly plaster applied to chicken wire, or canvas stuffed with foam rubber - all sorts of things you can find in stores. Pants and shirts. Furniture. A whole lingerie counter with a mirrored top. And most deliciously, there's food. Glorious food. Succulent slices of pie and cake. In an exhibition catalog entry in 1961, Oldenburg made a famous manifesto: I am for the art that a kid licks after peeling away the wrapper. I am for an art that is smoked like a cigarette, smells like a pair of shoes. I am for an art that flaps like a flag or helps blow noses like a handkerchief. I am for an art that is put on and taken off, like pants, which develops holes, like socks, which is eaten like a piece of pie.

At the MoMA show, there's a huge nine-foot-long wedge of cake called "Floor Cake" sitting on the floor next to a seven-foot-wide hamburger called "Floor Burger" that you have to walk around. I am for the art of underwear and the art of taxicabs, Oldenburg wrote. I am for the art of ice cream cones dropped on concrete.

Lying near the gigantic hamburger is the 11-foot-long "Floor Cone." I particularly love the small burlap and plaster "Baked Potato," with its pat of melting butter, and the "Banana Sundae," with its accompanying spoon painted with drips of enamel ice cream.

An actor, Hamlet says, holds a mirror up to nature. Just so, Oldenburg's art reflects the lives we live. I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life, that twists and extends impossibly and accumulates and spits and drips and is sweet and stupid as life itself.

It's both high tragedy and low comedy that for most of us our lives are so ordinary, that everything in "The Store" is for sale, our daily commerce. But that's part of the joy and pain of this wonderful exhibit that makes us smile so hard at the idea that our ordinary lives are so completely surrounded by, and enmeshed in, potential works of art.

GROSS: Lloyd Schwartz teaches in the creative writing MFA program at the University of Massachusetts Boston and is the senior editor of classical music for the online journal New York Arts. He reviewed "Claes Oldenberg: The Street and The Store," which is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through August 5. You can see photos of several of the works Lloyd referred to on our website, freshair.npr.org, where you can also download podcasts of our show.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.