Guests

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on February 2, 2005

Transcript

DATE February 2, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

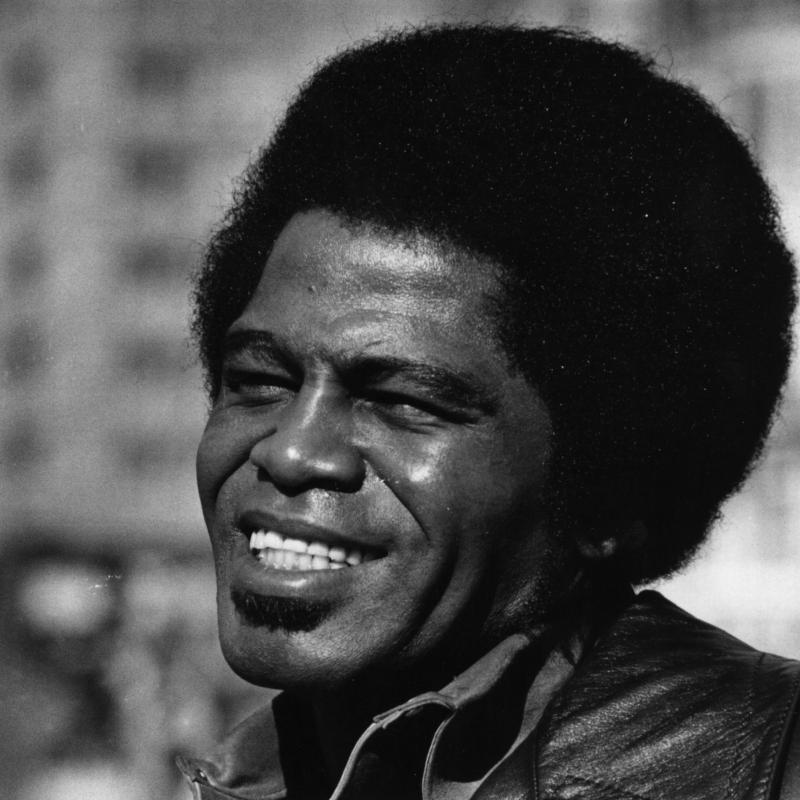

Interview: James Brown and Tomi Rae Brown discuss their lives and

career

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

We've always wanted to have James Brown on our show. The publication of his

new autobiography has given us that opportunity. The book is called "I Feel

Good." Along with James Brown, we'll also meet his wife, Tomi Rae. She's a

singer in his band.

Although I always introduce our guests, I think there's someone who can

introduce James Brown a lot better than I can.

Unidentified Man: So now, ladies and gentlemen, it is star time. Are you

ready for star time?

(Soundbite of audience)

Unidentified Man: Thank you and thank you very kindly. It is indeed a great

pleasure to present to you at this particular time, national and

internationally known as the hardest working man in show business, the man to

sing "I Go Crazy," "Try Me," "You've Got the Power," "Think," "If You Want

Me," "I Don't Mind," "Bewildered," million-dollar seller "Lost Someone," the

very latest release, "Night Train," "Let's Everybody Shout and Shimmy," Mr.

Dynamite, the amazing Mr. Please, Please himself, the star of the show, James

Brown and The Famous Flames.

GROSS: James Brown, Tomi Rae Brown, welcome to FRESH AIR.

James Brown, I want to start with your first record, recorded in 1956,

"Please, Please, Please."

Mr. JAMES BROWN (Singer): Right.

GROSS: Now I understand this record almost didn't get released. You know,

your new book says that the owner of King Records, Sid Nathan, didn't want you

to release this. What didn't he like about "Please, Please, Please"?

Mr. BROWN: Well, the repetition, because I continually say, "Please, please,

please." And he heard me say "Please, please" 26 times, and they'd never, you

know, had that kind of concept or that kind of music. It was that gospel

ballads, you know. And he couldn't understand pulsating bam, bam, bam,

please, please, please. He couldn't understand that. But that was a new

arising coming by him, totally different from what he'd heard before.

GROSS: Well, I guess they made a mistake. So...

Mr. BROWN: I'm glad. I'm glad they did.

GROSS: Yeah. So let's hear your first single, "Please, Please, Please."

(Soundbite from "Please, Please, Please")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please, please.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Please, please, whoa, whoa.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Please, please, whoa, whoa.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Honey, please don't go.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Go.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Oh, yeah. Oh, I love you so.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Please, please, whoa, whoa.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Baby, you did me wrong.

Backup Singers: (Singing) So you done me wrong.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Well, well, you done me wrong.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Oh, you done me wrong.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) So you done, done me wrong.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Whoa.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Yeah. Oh, yeah. Took my love, and now you're gone.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Please, please, whoa, whoa.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please, please.

Backup Singers: (Singing) Please, please, whoa, whoa.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please, please.

GROSS: That's James Brown recorded in 1956. He has a new memoir. It's

called "I Feel Good."

Now we've all heard your emcee introduce you over the years.

Mr. BROWN: Yes.

GROSS: Why did you want an emcee to introduce you in this fantastic way?

Mr. BROWN: Well, because it's dramatic. It dramatizes a lot, and it's the

buildup what show business should be about. Show business should really be a

buildup, and then once you go into it, you, like, live it. But it should be a

great fanfare and a production. And that gives to the people the chords,

different chords, different kind of way to say it. The same as a minister

would do in a church, chords would do to his team, not to have a way of

getting started. That's probably the best way that I know of. It's a

dramatic introduction.

GROSS: Did you tell him what to say?

Mr. BROWN: Yes.

GROSS: And one of the things your emcee has always done was, like, put on

your cape, take off your cape. Why did you want to wear a cape?

Mr. BROWN: The cape is because I saw a wrestler by the name of Gorgeous

George, and Gorgeous George was a flamboyant wrestler. And he wore curls in

his hair at that time and he was really sharp and really different, a little

early for most people. You expect him to win if he didn't win, so it was kind

of a thing where he was a great wrestler, so it made great for his production.

It made him quite--Gorgeous George reminded me a lot of Hulk Hogan.

GROSS: The wrestler, yeah. Mm-hmm. Now have you always had your clothes

made for you?

Mr. BROWN: Most of the time, I design them. I started wearing red suits

years ago, and they thought we were crazy. But we wanted people to say,

`There he is,' not `Where he is?' And the same thing applied to The Famous

Flames, which were working for me, right, Tomi?

Mrs. TOMI RAE BROWN (Wife): That's right.

Mr. BROWN: You know, and I do the same thing with Tomi Rae right now and

make sure her clothes are designed different. And a lot of times, she don't

agree with me, but that unique way and that individual look is very important.

It's the same thing I have right now.

GROSS: My guest is James Brown, and he has a new memoir called "I Feel Good."

Speaking of "I Feel Good," I want to play "I Got You (I Feel Good)," one of

your most famous songs. You have two versions of this. The first one you

didn't release. You weren't happy with it. This was in 1964. What was wrong

with the original version? What made you think it's not ready yet, it's not

right yet?

Mr. BROWN: You've got to get it where it synchs with the people or where

they're at, you know. "I Feel Good" was cut first with the jazz concept

because I have a broad and a great--more of ability to do more than one kind

of music or hear one kind of thing. There's so many directions that I go in,

you know. So what I did, I went back, and at about 4:00 in the morning, I

called--my bandleader at that time was called--his name was Nat Jones. I

recorded "I Feel Good" in Chicago, and it was too sharp, too slick, had a

baritone, you know, and the syncopation was so sharp. So I had to cut

something.

It was like, `I feel good. Da na na na na na na. Dit dum dum dum. Da na na

na na na na.' We gotta have staccato. We'll hit right on all at once, `Dit

dum dum dum.' And then the drum, `dit dit dit dit dit dit dit.' So what did,

we wanted to get more of a funk feeling and a sanctified feeling, so we

changed it and slowed it down. `Ow! I feel good. Ja do da do da do da. Ja

da do do da. Ba dum.' That's two different kind of things, see. One is jazz

because of sharp mixes. The other one is kind of laid back and gave it a

little rock 'n' roll feeling at that time as well. So we went with the laid

back cut, because that fit the street and fit the dancing. It's a good thing

I could dance, because by being able to dance, I could really tell that the

new arrangement, the new concept I had for it really fell right in place.

GROSS: What was the difference between the dancing you could do with the

second version compared to the first?

Mr. BROWN: Well, you could do the street dances. The first version--you

might do ballroom and everything with it, but the second version is for people

who get down in the street.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BROWN: And we need street action. That's basically what's wrong with

the music today. A lot of it don't go street.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear both of these versions back to back, the

unreleased and the released version of James Brown "I Got You (I Feel Good)."

Mr. BROWN: Well, you'll notice that the unreleased has a baritone in it with

a heavy sound, and the other one don't have the baritone. You'll see the

difference.

GROSS: Let's hear it.

(Soundbite from "I Got You")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Ow! I feel good. I knew that I would now. Ow! I

feel good. I knew that I would now. So good, so good. I got you. Ow! I

feel nice, like sugar and spice. I feel nice, like sugar and spice. So nice,

so nice, 'cause I got you.

(Singing) And I feel nice, like sugar and spice. I feel nice, like sugar and

spice. So nice, so nice. I got you. Wow! I feel good. I knew that I would

now. I feel good. I knew that I would. So good, so good, 'cause I got you.

So good, so good, 'cause I got you. So good, so good, 'cause I got you. Hey!

Oh yeah!

GROSS: That's two versions of James Brown's "I Got You (I Feel Good)." He

has a new memoir which is also called "I Feel Good."

Mr. Brown, the way you start that record with your--if I do it, I'll sound

ludicrous, but, you know, the `Ow' at the very beginning. It's so great. Can

you talk a little bit about how you started doing that?

Mr. BROWN: Well, the screaming and stuff comes--I must admit one thing about

it. A lot of the screaming was during that time when Little Richard was real

big and Roy Brown, people like that. The screaming kind of came down the

line, but Little Richard really was responsible for more screaming than I am,

because he used to do that `Oooh,' all that stuff years ago, and he was more

or less into it. He was sanctified, and out of the Holy Bible he was

sanctified, you know. So we kind of just borrowed things a lot from each

other, but Little Richard was very instrumental in a lot of the screaming.

GROSS: My guests are James Brown and his wife Tomi Rae. Brown has a new

memoir called "I Feel Good." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite from song)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Maceo, come on now, brother. Put it way back now. Oh,

let me have it.

(Soundbite of saxophone)

GROSS: My guests are James Brown and his wife Tomi Rae Brown. Brown has a

new autobiography called "I Feel Good."

Well, shortly after you recorded "I Got You," you recorded "Papa's Got A Brand

New Bag," and I want to quote something that you say in your new memoir "I

Feel Good." You say, `"Papa's Got A Brand New Bag" changed everything again

for me and my music. I didn't need melody to make music. That was, to me,

old-fashioned and out of step. I now realized I could compose and sing a song

that used one chord or two at the most.'

Mr. BROWN: Yeah.

GROSS: How did you start reducing your songs to being more about rhythm than

about melody?

Mr. BROWN: What I did was that I brought--a lot of my songs had melody, but

like, "I Feel Good," that's a melody and all that stuff, but rhythm all the

way through the song, and ours was just--I mean, even rock 'n' roll stuff had

melody, you know, but I went with more of a jazz concept gospel situation.

Like, I was talking to Tomi, and Tomi Rae, she have--her rock 'n' roll stuff

has melody but then all of a sudden, after she married me, she started to

getting Holy Ghost, though she didn't know it. Why she was going over and

over, she used to sing with us, one of the quintet. See, you know, coming

from the black community you have a lot of Holy Ghost, you know, and a lot of

gospel. And Tomi Rae got over to me and started doing the Holy Ghost thing.

So the melody don't really fit when you get into music they got today.

GROSS: Now at about this time, your beat really starts shifting from the two

and the four to the one and the three. Can you talk a little about...

Mr. BROWN: Well, actually...

GROSS: ...that shift? Yeah, go ahead.

Mr. BROWN: It started that with "Papa's Bag."

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BROWN: From that point on, it was one and three. And even before "I

Feel Good," "Papa's Bag" has a one and three.

GROSS: Can you maybe just clap for us the difference?

Mr. BROWN: Well, one is laid back and the other's not, like `da dee da bum.'

I say, the one has syncopation, `Dat dat do dat dat do dat, bat dat dat do,

bat dat dat.' I mean, that's the difference. You count it off right on the

one, `Bam, do bang bang.' And then the other one you'd say, `One and a two'

and you'd be on the two, see, but two is the upbeat, and I'm on the downbeat.

That's the difference.

GROSS: How did you start doing that?

Mr. BROWN: Well, because of the fact that I'm a musician and I sung gospel

well, and I know the difference. It's not how, which is easy to do. Why

would be the best thing. Why gives me a different feeling.

GROSS: And was it hard to convince the musicians that this would work, or did

they get it right away?

Mr. BROWN: No, I paid them.

GROSS: (Laughs)

Mr. BROWN: Paid them, and they played what I wanted and that was it,

because they would have never agreed.

GROSS: They would have never agreed to it?

Mr. BROWN: They would have never agreed.

GROSS: Why not?

Mr. BROWN: Well, because it was in their head that Mozart, Schubert,

Beethoven, Strauss and Bach, Chopin and ...(unintelligible) was correct. And

they'd tell me that I was wrong. So they thought that that was low in the

music. There's no low in the music. There's a freedom in music. That's why.

Tomi Rae never sang rock 'n' roll, right, Tomi?

Mrs. BROWN: That's right.

Mr. BROWN: You get tired of being bedded down to one thing. So you start

singing what you feel.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear "Papa's Got A Brand New Bag," which you

recorded in 1965.

(Soundbite from "Papa's Got A Brand New Bag")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Come here, sister. Papa's in the swing. He ain't too

hip about that new breed thing. He ain't no drag. Papa's got a brand new

bag. Come here, mama.

GROSS: That's James Brown recorded in 1965. He's my guest and he has a new

memoir called "I Feel Good." And we'll be talking more with his wife Tomi Rae

Brown in a couple of minutes.

Now some of the musicians in your band became famous in their own right later

on: Maceo Parker, Fred Wesley, Bootsy Collins. And, you know, I interviewed

Bootsy Collins a few years ago, and one of the things he said--I mean, he

loved playing in your band, but one of the things he said is that it was hard

for him to be so disciplined. It was around 1970, the era when you were

recording "Sex Machine," and he said, you know, `Everyone was freaking out,

but we were standing up there being the tightest band in the land, having to

wear suits and patent-leather shoes, and you couldn't jump out in the audience

and freak out and act crazy, and that's what we wanted to do.' Did you know

that someone like Bootsy Collins really wanted to, like, be wild and crazy

when you wanted this really tight, disciplined band?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I taught them organization. They didn't have organization.

And this was very important. You know, I wanted them where they could play at

West Point as well as play the street on the corner. I mean, West Point or

the Navy Academy place. I wanted them to be able to go in--see, when I wanted

to play "Papa's Bag" and stuff like that, I could play for the president and

I could go and play for the people in the streets. That's what you call being

totally accepted and being totally straight about what you felt.

GROSS: Can you describe what your rehearsals were like in, say, the 1960s or

early '70s?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I'll tell you, my rehearsals have always been very intense,

but, you know, for somebody who was with me and somebody who's not--is my wife

but also my employer and my artist. Would you explain how you feel in the

rehearsals, Tomi?

Mrs. BROWN: Well, first of all, it's an honor to be in a rehearsal room with

you, but when he walks into the rehearsal room, he commands performance, and

because of the respect in the room for him, people command themselves to

perform for him, and he knows every note. If you're off a note, I don't care

if 25 musicians are playing, he will find the bad note and who played it at

what time. He has got an ear that even the person that played the bad note

doesn't even know they played it.

GROSS: Wait, I'm going to stop you right there. When he hears...

Mrs. BROWN: He's just got an incredible...

GROSS: Excuse me for one second, but when he hears the bad note, what does he

do about it? I mean...

Mrs. BROWN: Oh, he stops, and he says, `You, you did this,' (makes noise) or

whatever, you know, he'll do with his voice, he'll make a sound, you know,

`and you're supposed to go'--(makes noise), and it'll be so--even just this

little minute difference, but he will hear it and know it, and he sings it to

them through his mouth and explains to them how to play it, because he's not

educated as far as writing music. He created the music, so he doesn't look at

sheet music. It comes from God, you know, and so he explains it with his

mouth, and it's very interesting to see, and everybody listens and then we get

it, you know, and then we start up and do it until it's right and we don't

leave until it's done.

GROSS: Is it ever embarrassing to be singled out that way?

Mrs. BROWN: Well, you know, it puts you on the hot seat, and when you first

start, yeah, you get embarrassed, and you might even be foolish and make a

fool of yourself because you're trying to stick up for something that--what

are you sticking up for? You've got the Godfather of Soul telling you how

it's done, and instead of being grateful and just listening and doing what

you're told to do, sometimes we think we know more than we do and, you know,

we need to look at who's teaching us here and really be thankful for that,

but, yeah...

Mr. BROWN: Thank you.

Mrs. BROWN: ...we do.

Mr. BROWN: Excuse me for saying--and then I can always go to the keyboard or

to the guitar, to the bass or to the drums or I can hum it out and whatever,

but I can show you a note...

Mrs. BROWN: Yeah.

Mr. BROWN: ...on five or six different instruments because I play most of

those instruments well enough to describe what I'm about.

Mrs. BROWN: And play most of them better than they do.

GROSS: Now do you ever find musicians--I know you used to find musicians,

didn't you?

Mr. BROWN: Oh, yes, I'll do it now, but, you know, the musicians--now they

have a lot more respect and they're more intent on doing it right, wouldn't

you say, Tomi?

Mrs. BROWN: Yeah. Well, you know, I mean, it's been eight years now of

learning, and every day still, I learn more about how to respect and how to

really be quiet and listen and learn the James Brown way, and it's a different

way. It's unorthodox. It doesn't make sense. It's not scripted. You can't

write it down. It's not musical terms. I read music, and it just doesn't

happen that way. Fred Wesley, I think, said it best, that it's just--he

doesn't now where it comes from. He says he doesn't know where it comes from,

but it can't be written on paper, and Fred Wesley was right. It's just James

Brown.

GROSS: So, Mr. Brown, what are some of the things you'd fined musicians for

back in the day?

Mr. BROWN: Oh, a lot of major things. I did a total program, like at West

Point. They've got to be clean, neat, the shirt got to be pressed, shoes got

to be shined, the suit got to be pressed. They've got to play correct. They

can't be looking off when they should be watching me because then they'll miss

something. I find them. Because I don't have time to disturb what I'm doing.

I mean, we're always going to get through it, but by the same token, those

people who'd rather not get fined so they have a little more discipline, and

that's another situation. I understand the president of the United States has

ways of making people account for themselves.

GROSS: What's the biggest fine you ever gave?

Mr. BROWN: I don't know. Maybe 500.

GROSS: James Brown and Tomi Rae Brown will be back in the second half of the

show. Brown's new autobiography is called "I Feel Good." I'm Terry Gross,

and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Oh! Lay it down.

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Oh, oh, oh, oh. I've got the feeling.

GROSS: Coming up, more with James Brown and his wife Tomi Rae Brown. Also,

Maureen Corrigan reviews Adam Hochschild's book "Bury the Chains," about the

18th century abolitionist movement in England.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) You don't know what you do to me. ...(Unintelligible)

now in misery. All right. Ow! Feeling like ...(unintelligible). Baby,

baby, baby, baby, baby, baby, baby, baby, baby, baby, baby, I've got that

feeling, baby. Baby, sometimes I'm up, sometimes I'm down. I'm around town.

(Unintelligible) was profound. Baby. I said ...(unintelligible) with the

sound. Ah! Baby.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with James Brown and his

wife, Tomi Rae Brown. She sings in the band. James Brown has a new

autobiography called "I Feel Good."

Now, I want to change musical directions for a second. And through your

career, you've recorded, you know, ballads as well as, you know, funk. And in

1969, you made an album with a jazz band, the Louis Bellson band, and it was

mostly or completely ballads on here. And I thought we'd listen to one of

those ballads because it's a really different side of you. You know, we were

talking before about how you kind of focus more on rhythm than melody in a lot

of your songs, but here you are really focusing on the melody. Can you tell

us why you wanted to record this album of jazz standards with a jazz band

behind you?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I really liked Oliver Nelson because he made those horns

shout.

GROSS: And he did all the arrangements on the record.

Mr. BROWN: Yeah, he did. I wanted his stuff. But, you know, my concept was

so different. There's so many concepts. I needed a key to turn me on, which

was a little hard for me because it was Louis Bellson's song, who was the

drummer, and his wife was Miss Pearly Bailey. It was different. It was also

different for me to do "It's a Man's Man's World," because I did "What Kind Of

Fool Am I," a Sammy Davis thing. And I knew I wanted to go to the other side.

And I know people do it, and I knew I wanted to do it, so it was really quite

an experience.

GROSS: Well, actually, that's the track I wanted to play, "What Kind Of Fool

Am I."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) What kind of fool am I?

Yes, I...

GROSS: It's so interesting to hear you sing like this, so why don't we play

it, and I'll sit back and listen?

Mr. BROWN: You know, you sound like you was getting ready to sing something

there.

GROSS: No, I wish.

Mr. BROWN: OK. Let's take a listen, then.

GROSS: OK.

(Soundbite of "What Kind Of Fool Am I")

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) What kind of fool am I, who never fell in love? It

seems that I'm the only one that I've been thinking of. Tell me, what kind of

man is this, an empty shell, a lonely self where an empty heart may dwell?

What kind of lips are these that lie with every kiss, that whisper empty words

of love, that left me alone like this? Why can't I fall in love like any

other man? And maybe, maybe then I'll know what kind of fool I am. Tell me,

tell me what kind of...

GROSS: That's my guest, James Brown, recorded in 1969 with the Louis Bellson

orchestra. And James Brown has a new memoir which is called "I Feel Good."

And Tomi Rae Brown is also in the studio, and we'll talk about how they met

and got married in a couple of minutes.

Did you ever want to be, like, a romantic crooner?

Mr. BROWN: Only when I sing sometimes soft to Tomi Rae, and she can't

believe it, because I have many voices that most of the young people don't

know about today, and she just kind of blush when I sing sweet songs to her.

What about--is that it? You say you like them?

Mrs. BROWN: You are such a romantic. And you know, your--some of the best

stuff I've ever--that I like is, like, "Messin' With the Blues." And when you

were really singing those soft, melodic, I mean, heartfelt songs, I mean,

those are the ones that really, really got me into James Brown to begin with.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Feeling a little down.

Mrs. BROWN: Yeah.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) I ain't got no frown.

Mrs. BROWN: I love it. I love it.

GROSS: What were some of the bands and who were some of the singers that

influenced you when you were growing up?

Mr. BROWN: Well, they were number one at that time--that's many, many years

go--Louis Jordan, L-O--Louis Jordan, L-O-U-I-S J-O-R-D-A-N. He went to

Caledonia, and one of the songs that Tomi Rae loved so much about me. Do you

remember that--which one?

Mrs. BROWN: "Why is Your Big Head so Hard."

Mr. BROWN: And "Ain't Nobody Here But Us Chickens."

Mrs. BROWN: That's right, "Ain't Nobody"--`a da la da la da la, it's a sin.'

Yeah, that's right.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Ain't nobody here but us chickens, and, haba haba haba

haba, it's a sin.

GROSS: Now I mentioned that the album of ballads was recorded a year after,

"Say It Loud." Let me ask you about "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud."

You say in your book that a lot of--you think a lot of white people

misinterpreted the meaning of the song.

Mr. BROWN: I think they didn't understand it, because I said, `I'm black,

and I'm proud.' I think they thought it was some kind of a revolutionary or

something that would separate us or something that would preach black power

and come into violence. But what they didn't know, we was trying to--I let

them know that we should be proud of who we are and not feel down and left

out. And later on, some whites asked me to record it again, because they

thought it was getting a little hairy in the streets, and they thought that

blacks should be a little bit more proud of themselves and not go off and

worry about what the Caucasians are doing or China, German or whatever. They

thought it was a great idea later on.

GROSS: What inspired you to record it in the first place?

Mr. BROWN: Well, they--I was in Vegas--I mean, in LA. And during that time,

some police had shot four or five Muslims from the Islamic world, and it

became a real mess there. So I went and recorded "Say It Loud, I'm Black, I'm

Proud" and tried to send a message, not only to the white, but to the black as

well, that pride was important and not power. The word `power' and `pride'

were so misunderstood, and I thought that pride was more important. It

doesn't mean I'm black and I'm bad, but black and I'm proud.

GROSS: Well, let's hear it, and this is James Brown recorded in 1968.

(Soundbite of "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Uh! Let your bad self say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Looky here. Some people say we got a lot of manners,

some say a lot of nerve. But I say we won't quit moving until we get what we

deserve. We've been 'buked, and we've been scorned. We've been treated bad,

talked about, as sure as you're born, just as sure as it take two eyes to make

a pair. Ha! Brother, we can't quit until we get our share. Say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) One more time. Say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) I've worked on jobs with my feet and my hands. You

know, all the work I did was for the other man. And now we demand a chance to

do things for ourselves. We're tired of beating our head against the wall and

working for someone else. Say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Say it loud.

Backup Vocalists: (Singing in unison) I'm black, and I'm proud!

GROSS: My guest, James Brown, and he has a new memoir which is called "I Feel

Good."

One other record I want to ask you about, and that's "Sex Machine," recorded

in 1970, one of your really big hits. And you know, pop songs have always

been about love and sex, but they never really used the word `sex' before in

the lyrics, I think.

Mr. BROWN: Yeah.

GROSS: What made you decide to actually use the word `sex' in "Sex Machine?"

Mr. BROWN: Well, sex, I don't know, you're not far from it with the dancing

and all that stuff and the emulations that they do when they get on the floor

of the ballroom, two-stepping, the funky chicken or the James Brown, all these

different things. So--and that's what's in your mind if you go by a pool and

see young ladies out there in their bathing suits, swimsuits, because the men

don't ...(unintelligible), women do.

I decided I would use that term, because we was at this dance, I mean, this

fellow and girl was at this dance. And she was just sitting there, and he's

sitting there. Nobody's doing anything. It was kind of just almost like

wallflowers till the fellow jumped up and said, `Get up. I feel like being

like a sex machine, and let's dance.' So that started it. That was the

concept.

And it's not about or relating to somebody else's girl or man. It's saying,

`I got mine, don't worry about his. The way I like it, the way it is. I

mean, ...(unintelligible) fine. I got mine, don't worry about his,' you know.

GROSS: Was anybody worried, either your producers or disc jockeys about...

Mr. BROWN: No, it was produced by James...

GROSS: ...playing a record with the word `sex' actually in it?

Mr. BROWN: James Brown was the producer, so it wasn't no problem.

GROSS: OK. Here's "Sex Machine," recorded in 1970.

(Soundbite of "Sex Machine")

Mr. BROWN: Fellas, I'm ready to get up and do my thing.

Unidentified Men: Go ahead, go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: I want to get into it, man, you know...

Unidentified Men: Go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: ...like a sex machine, man...

Unidentified Men: Yeah! Do it!

Mr. BROWN: ...moving, doing it, you know?

Unidentified Men: Yeah!

Mr. BROWN: Can I count it off?

Unidentified Men: Go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: One, two, three, four.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Stay on the scene.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Like a sex machine.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Stay on the scene

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Like a sex machine.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Stay on the scene.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Like a sex machine.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Wait a minute. Shake your arms, then use your form.

Stay on the scene like a sex machine. You got to have the feeling, sure as

you're born, and get it together. Right on, right on. Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Ha! Get up.

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) Get on up.

GROSS: That's James Brown. He has a new memoir called "I Feel Good."

How did you learn to dance and specifically, to do splits?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I guess that it come from playing baseball...

GROSS: Wait a minute.

Mr. BROWN: ...because during that time...

GROSS: Most baseball players do not do splits.

Mr. BROWN: Well, now they don't, but those years, Jackie Robinson, the first

black man came into major league baseball, and he was doing the split on first

base. And they thought that was absurd. They thought--they couldn't believe

it, but it was like ...(unintelligible) clowning. There was another black

baseball team called the Indianapolis Clowns, and the Kansas City Monarchs

before ...(unintelligible). Those were Negro Leagues. And eventually, when

Robinson got into major league baseball, he brought some of those tricks with

him. You know, we missed so much, because had those black men ever been able

to play baseball then, it would be like the courts is today. Ninety percent

of all the players are black.

GROSS: My guests are James Brown and his wife Tomi Rae. Brown has a new

memoir called "I Feel Good." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Man #2: Thank you. And now, the star of the show--let the

brother rock--James Brown!

GROSS: My guests are James Brown and his wife Tomi Rae. Brown has a new

autobiography called "I Feel Good."

So you first, I think, danced when you were a kid, and you danced on the

street for pennies.

Mr. BROWN: I danced to pay the rent, for the soldiers. And me and Tomi Rae

goes by there a lot, and I know she like to take little James by, because she

want him to see more or less--well, explain what you say to me, why you go by.

Mrs. BROWN: Well, I like to show our son, I want him to know where his

father came from. I don't want him to think that he was born into this James

Brown succession and that he has a right to it, because he doesn't. He was

just blessed to be born. And so I want him to know his father and where he

came from and the hardships that his father went through so that he could have

the things that he has. So I make it a point to educate my son on what his

father has done.

GROSS: Tell us about some of those hardships, about what life was like when

you were very young. James Brown, your mother left when you were four, I

think, and you were--you lived...

Mr. BROWN: Yes.

GROSS: ...with an aunt. What was the house like?

Mr. BROWN: Well, it was very, very hard. I didn't have a place, because my

mother left. And my dad took me to see my grand aunt--Great-Aunt Anita Brown.

She raised me and kind of baby-sitted me while my daddy did basic menial work

that just didn't have any skill about it, but they had to go all over the

country to find work, somewhat like they're doing now, had to find a place

that common labor can make it, you know. They didn't have a lot of room for

common labor even in those days. That's why I'm telling kids to get education

today, because you never know what's going to be out there for you and if

there'll be anything for you, so it was very, very hard.

That's one reason why Tomi Rae and I became man and wife, because she came up

the hard way that way, and we were related. I mean, you know, it don't take

color purely. It takes character and the contents of your character, like Dr.

King said. And people can know someone and don't even know their name,

because--their upbringing.

GROSS: Tomi Rae, James Brown, you've been married now for how long?

Mrs. BROWN: Well, we've been married for three years on December 14th.

GROSS: How did you meet?

Mrs. BROWN: And we met--actually, I was doing the Janis Joplin show for

Legends in Concert in Las Vegas, and I was doing her act. And one of her old

sing--his background singers that used to do background singing for him,

Candice Hurst, I taught her how to write a song and play guitar about 20 years

ago. And she said, `I want to pay you back for it.' And I said, `What are you

talking about?' And she said, `Do you want to audition to sing for James

Brown?' I said, `Are you kidding?' So I did. I went there, and I met him, and

I said, `Hello.' And I sang a cappella. I think I sang "Mercedes Benz" for

him or something, and he said, `You're not a background singer.' And at that

point, I thought that I didn't get the job, but in fact, he hired me and my

band to be the opening act for him. And me and my band traveled with him

throughout Europe. And it became a problem traveling with two separate bands,

so he then involved me into his group. And now I'm his lead soloist, and I

also do the backgrounds for his music as well.

So now, it's just there. After we did that, you know, I was so impressed with

watching him command the stage and the rehearsal room and the studios that I

just started falling in love with this man and what he did. And the more I

learned about what James Brown was and the things that most people don't know

that he did for our country and for humanity, and it made me fall in love with

this man. And we started dating, and then we had our son. And we decided, at

that point, it was time to get married, so we did.

GROSS: What would you say you learned about singing or music in general,

about rhythm, from working with James Brown?

Mrs. BROWN: Well, I learned I didn't know anything before, and I really know

little now, and every day, I'm learning more. And the minute that I think I

know something is when I'm dead before I start, because there's always

something new for me to learn. But I've learned to be a better singer. I

have learned to take more control of my notes. I've learned to take more

control of my lifestyle. I've learned that this business has a lot more

knocks and bumps in the road than I ever thought it would, and that it's

really, really a rough business. And had he not given me the opportunity, I

can see now that I'm in it, that I never had a chance. And I really, really

believed in the dream that I could make it, and it's so hard for someone to

make it.

Mr. BROWN: But Tomi has really just not just turned her music around, but

she's turned her concept around to how to face music. And her stage

presentation's just awesome. She is really--not because on her backside, her

name is Brown, but she's always been Tomi Rae to me. And I'll tell you that I

just enjoy the fact that when a person can--she just tires herself at work.

She just beats herself up, and I admire her for that, because I do the same

thing. Tomi.

Mrs. BROWN: And I just want to tell you, thank you so much. You know, we

listen to NPR all of the time, and I definitely remember--I know your name. I

know your voice. I've heard you on your shows, and I just want you to know

that we listen to you all the time.

Mr. BROWN: Oh, you got a couple of fans here.

Mrs. BROWN: Yeah.

GROSS: Oh, that's great.

Mrs. BROWN: And I thank you very much.

GROSS: That's great. Thank you very much. And just one more thing, and I'll

let you go. Mr. Brown, what's it like for you to have the same woman be both

your wife and your lead singer?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I'll tell you, it causes a lot of squabbles, you call it,

but they're house squabbles that leads into craziness sometimes. But we love

each other very, very much, and I'm going to continue being the same kind of

person, dominant when it comes to my music and my business. And I compromise

as a husband, but not as a leader or manager.

GROSS: I thank you both so much for talking with us.

Mr. BROWN: God bless you.

Mrs. BROWN: Thank you.

Mr. BROWN: We love you.

Mrs. BROWN: Have a wonderful new year.

GROSS: You, too.

James Brown has a new autobiography called "I Feel Good."

(Soundbite of "I Feel Good")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) So good, so good, I got you! Hey! Oh, yeah!

GROSS: Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews Adam Hochschild's new book about

the abolitionist movement in England. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: "Bury the Chains" by Adam Hochschild

TERRY GROSS, host:

Adam Hochschild's award-winning book "King Leopold's Ghost" explored the

history of European rule in the Congo and was praised by critics for being

both scholarly and entertaining. His latest book, "Bury the Chains," is also

a narrative history, one that chronicles the struggle to end slavery

throughout the British empire. Book critic Maureen Corrigan has a review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN:

If "Bury the Chains" were nothing else but a narrative history of the 18th

century citizens' movement to end slavery in the British empire, it would be a

terrific book. Author Adam Hochschild knows how to tell a story, and what he

calls this ragged and untidy epic of the first grassroots human rights

campaign is marked by cliffhangers, inspiring acts of lone defiance, bloody

revolutions, saving twists of fate and a cast of characters even Dickens might

have deemed too over the top.

But Hochschild aims for something even more ambitious and elusive than

uncovering the story of this largely forgotten anti-slavery movement. He aims

to trace the evolution of an emotion, the emotion of empathy among the late

18th- and early 19th-century British citizenry. As Hochschild says in his

first chapter, `There is always something mysterious about human empathy and

when we feel it and when we don't.' Slaves and other subjugated people have

rebelled throughout history, but the campaign in England was something never

seen before. It was the first time a large number of people became outraged

and stayed outraged for many years over someone else's rights, and most

startling of all, the rights of people of another color, on another continent.

Hochschild begins his account at a moment when this curious emotion of empathy

for the empire's slaves makes its first public display. In 1787, 12 men, many

of them religious dissenters, gathered at a London printing office for the

purpose of discussing how to end slavery. As Hochschild vividly demonstrates,

the group may as well have been strategizing how to turn the sky orange. The

economy of the British empire was absolutely dependent upon slavery, from the

sugar cane plantations of the West Indies to the rope-making and shipbuilding

industries based in England itself.

So who were these oddballs who thought they could change the world? And how

did some of them come to gather at that printing shop? As Hochschild

describes them, the leaders of the British anti-slavery movement were as

various and sometimes quirky as the sources of their life-altering leaps of

empathy.

Thomas Clarkson, whom Hochschild dubs one of the towering figures in the

history of human rights, was a gangly 25-year-old divinity student at

Cambridge in 1785 when he wrote a prize-winning Latin essay on the assigned

topic: Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will? Clarkson

took the striking position that it was not. And evidently, his argument was

so persuasive that he, himself, was won over by it. For decades hence, he

traveled England by foot and horseback, gathering damning testimony from,

among others, disgruntled slave-ship crew members about the evils of the

trade.

James Stephen was a dissolute ladies' man when he landed in Barbados in 1783

to make his fortune. The scales fell from his eyes when he witnessed a murder

trial where two slaves were sentenced to death by being burned alive.

John Newton, author of the hymn "Amazing Grace," was a former slave-ship

captain who, very late in life, repented, long after he wrote the hymn, by the

way.

As these men and others like them began to agitate for an end to the slave

trade, Hochschild says they invented many of the political tools that

activists today still rely on--wall posters, lapel buttons, mass mailings and

boycotts.

Naturally, one of the pitfalls for white middle-class readers of this saga

that largely features the heroism of white middle-class abolitionists is that

we'll end up feeling all warm and self-congratulatory about our kind.

Hochschild stresses throughout that the work of these 18th-century white

crusaders would have come to naught were it not for the courage of escaped

slaves who testified about the barbarism of their situation in court, as well

as for the tireless campaigning of singular figures like Olaudah Equiano, an

ex-slave whose best-selling memoir, first published in 1789, ushered white

readers into the fetid cargo holds of slave ships.

Hochschild exhaustively explores all of these and scores of other events,

bombarding readers with statistics, biographies of minor but pivotal

characters and economic and maritime background history, all without doing

damage to the suspenseful pace of his main narrative. Hochschild does such a

brilliant job of accustoming his readers to the inevitability of slavery that

when the institution is finally abolished in the British empire in 1838, it's

hard at first to take in such a monumental shift in the order of things.

"Bury the Chains" is a thrilling, substantive and oftentimes raw work of

narrative history. In its own fashion, it furthers the abolitionists' crucial

work of lifting our moral blindness.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She

reviewed "Bury the Chains," by Adam Hochschild.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.