King Records And The Beginning Of Bootsy Collins

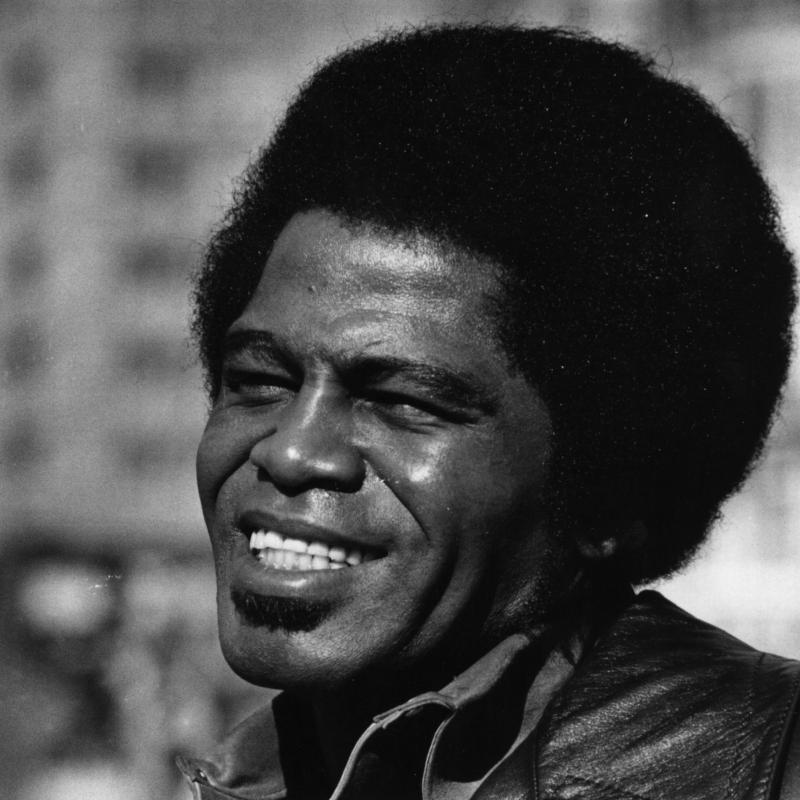

Funk bassist and psychedelic soulster Bootsy Collins is known for his solid grooves and flashy style. Collins got his start at Cincinnati's famed King Records, where he began as a session musician before joining James Brown's band, The JBs.

Other segments from the episode on October 15, 2009

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20091015

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Beginning Of Bootsy Collins

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Iâm Terry Gross. Today, the story is King Records.

(Soundbite of song, âThe Twistâ)

Mr. HANK BALLARD (Singer): (Singing) Come on, baby, letâs do the twist. Come

on, babyâ¦

GROSS: Thatâs Hank Ballard, with the original record of âThe Twist,â a song

later made famous by Chubby Checker. Ballardâs version was on King Records, an

influential, independent label that was founded by Syd Nathan, who ran it from

1943 until 1971. King also recorded the original versions of âFeverâ and âGood

Rockinâ Tonight,â not the most famous label, but this Cincinnati-based label

was very influential. It launched the careers of James Brown, Hank Ballard,

Cowboy Copas and Freddie King.

In a time of racial segregation, it recorded country, blues and rhythm-and-

blues performers, including The Delmore Brothers, The Stanley Brothers, Earl

Bostic and Ike Turner.

Today, weâre going to hear the story of King Records from Jon Fox, the author

of a new book about the label, Seymour Stein, the founder of Sire Records who

learned the music business at King, and Bootsy Collins, who was a studio

musician at King, where he joined James Brownâs band.

Weâll start with an excerpt of our James Brown interview. Brown not only got

his start at King, where he became their biggest seller, his first single,

âPlease, Please, Please,â was released in 1956 on Kingâs subsidiary label,

Federal Records. In our 2005 interview, I asked James Brown about âPlease,

Please, Please.â

Now, I understand this record almost didnât get released. You know, your new

book says that the owner of King Records, Syd Nathan, didnât want you to

release this. What didnât he like about âPlease, Please, Pleaseâ?

Mr. JAMES BROWN (Musician): Well, the repetition, because I continue to say

please, please, please. And he let me say please, please 26 times, and didnât

ever, you know, have that kind of concept of that kind of music. It was that

gospel ballad, you know, and he couldnât understand the pulsating bam, bam,

bam, please, please, please. He couldnât understand that, but that was a new

arising by him, totally different from heâd heard before.

GROSS: Well, I guess they made a mistake.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Soâ¦

Mr. BROWN: Iâm glad they did.

(Soundbite of song, âPlease, Please, Pleaseâ)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please, please.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) (unintelligible)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) (unintelligible)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Darling, please. Oh. Oh, yeah. Oh, I love you so.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) (unintelligible)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Baby, you did me wrong.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) You know you got (unintelligible).

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Whoa, whoa, youâve done me wrong.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) You know youâve done me wrong.

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) So you done, done me wrong. Oh, yeah, took my love, and

now youâre gone.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) (unintelligible)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) Please, please, please, please, please, please, please,

please, please, please, honey, please. Oh, oh, yeah. Love, I love you so.

Unidentified Group: (Singing) (unintelligible)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) I just want to hear you say I, I, I, I, I, Iâ¦

GROSS: âPlease, Please, Pleaseâ on the King Record label. King launched James

Brownâs career, and thatâs where bass player Bootsy Collins got his start at

the age of 15. He was a King studio musician, and then joined James Brownâs

band. He later formed his own group, Bootsyâs Rubber Band. I asked Bootsy to

share some King memories.

Bootsy Collins, welcome back to FRESH AIR. So you grew up in Cincinnati, where

you still live and where King Records was based. So before you ever started

playing at King, did you buy King Records?

Mr. BOOTSY COLLINS (Musician): Yeah. Well, actually, I probably didnât buy them

because at that time, we had a couple of friends over at King Records who

actually kind of slid us a 45 or two.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COLLINS: You know, so anything we kind of wanted, you know, we kind of, you

know, asked him, and, you know, he knew we didnât have any money. We was a band

playing around Cincinnati. You know, nobody really had any money at that time.

So he kind of, you know, gave us this, that and the other, whatever we asked

for.

GROSS: Now, before you started playing with James Brown for King Records, you

became part of the King house band.

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah.

GROSS: So how did you do that? How did you get that job?

Mr. COLLINS: Well, actually, we were like pests over at King Records. We were

always there. We were always wanting to see who was going into King Records.

Who wereâ¦

GROSS: We being you and the members of your band, including your brother?

Mr. COLLINS: Yes, my brother and Frankie(ph), the drummer. And actually later

on it became Robert McCullough(ph) and a guy named Chicken that played the

horn. They came in later, but the rhythm section was the ones that started off,

and that was the three of us.

And so we started just kind of hanging around over there and just to see the

artists coming in. We had no idea we was going to actually get a chance to go

in King, you know, because they never let nobody in unless you were an artist

and that you were performing and you were doing something, recording.

So we were just kind of like fans, I guess you would call. And then we met this

guy, Charles Spurling, who was an A&R guy over there at King Records, and he

had heard about us, and he wanted to come and see us play.

We had talked about it, talked about ourselves so much, you know, and he wanted

to come and see us. So he came to see us at a club, and he thought that we were

great. He thought that we was, like, we would bring a lot of energy to the new

rhythm section that he was looking for. So he invited us over to King Records,

and that was the first time we got in King Records.

GROSS: So what was it like when you got inside?

Mr. COLLINS: Oh, man. Oh, man. I mean, you from, from all that fighting to get

in, you know, it was like, wow, we didnât know what to do with ourselves, you

know. It was pretty amazing. I mean, it was one thing to see an artist going

into the studio, but to actually be in the studio, and you see them, and you

hear them recording and putting songs together - it just took a whole other

level for us. We were in heaven.

GROSS: So when you were in the house band and you were playing with different

performers, what were some of the things that you learned musically by watching

different kinds of performers record and by having to follow them, you know,

backing them up?

Mr. COLLINS: Well, you know, I would have to say the main thing, I guess, was

we went over there. Iâve got to tell you a little story, since you asked that

question. We went over there, and they didnât really know how much we knew as

far as recording and - because, you know, they liked our energy so much, and

they liked the fact of how we made the records feel. So I think that king of

helped override what we really knew. So at some point, they was going to test

us. So the big test was, okay, letâs put some music in front of these boys and

see how they do.

So one of the guys, one of the arrangers over there who actually became James

Brownâs string and horn arranger, Dave Matthews, he actually put some music in

front of us. Because before that, we were just kind of winging it, meaning that

we were playing what we felt to the song that they were doing. But I think they

wanted to see, okay, can these boys really read, or how advanced are they?

So they put music in front of us, and we kind of sit there, me and my brother.

I never will forget. We looked at each other, because we was saying to

ourselves, how in the heck are we going to get out of this?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COLLINS: Because, you know, neither one of us could read music. I mean, you

know - and they sit it in front of us, and we had Henry Glover there, who was

like the top producer, and all of them was looking at us. We had this big

orchestra in there, horns, strings, and we were the rhythm section. So it was,

like, oh my God.

So we were on the spot. And I said come on, cat, we can do this, and I said,

Dave, can you run it down one time so we can see how it goes? So he ran it down

with the whole band, you know, without us, and I said give it to us one more

time so we can get a real good feel for it because we want to do this right. He

ran it again, we said we got it.

We played that sucker one time, and they took it, and it was a take, and they

loved it. And about two or three weeks later, after, you know, grueling

sessions like that, two or three weeks later, Dave pulled me to the side. He

said: You know I know you canât read. And I kind of looked at him and started

cracking up, and he started laughing. And he said I understood that you

couldnât read in the â you know, the very first time you played that first

song. He said I knew you couldnât read. He said but I liked what you did so

well that it didnât even matter.

He said: Now, I want to spend some time with you. I want to at least teach you

some chord changes and how to read chord changes, you and your brother. And

that way, we can get through this a lot easier, and you wonât have to feel so

crushed in these sessions. I said okay, cool.

So he pulled us - he took us to the side and started teaching us how to read

chord changes. And thatâs how we made it through, you know, those sessions.

GROSS: Well, Bootsy Collins, thank you so much.

Mr. COLLINS: Oh, this was awesome.

GROSS: Bootsy Collins got his start at King Records. Weâll talk with the author

of a new book about the label after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

113824955

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20091015

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

The Whole Story Of The 'King Of The Queen City'

TERRY GROSS, host:

Weâre talking about King Records, one of the most important independent labels

of the 1950s. It launched James Brownâs career and recorded a mix of country,

blues and rhythm and blues performers, including The Stanley Brothers, The

Delmore Brothers, Lonnie Johnson, Hank Ballard and Earl Bostic.

My guest, Jon Fox, is the author of a new book about the Cincinnati-based label

called âKing of the Queen City.â

Jon Fox, welcome to FRESH AIR. You describe King Records as helping to

integrate America through music. So what do you mean by that?

Mr. JON FOX (Author, âKing of the Queen Cityâ): Well, King, from the â pretty

much from the very beginning of the company in the mid-1940s, had a relatively

colorblind approach to music. Syd Nathan, the founder of the label, always said

that he made music for the little man, and he felt that he was an outsider to

mainstream society. So he was very conscious of trying to do the music, trying

to satisfy the musical consumers that the major record labels werenât doing.

One of the ways, or one of the things that he found out doing that was that

black and white music, which was kept pretty segregated by record companies and

record stores and consumers, was essentially the same thing. If you peeled back

one label, country music and blues and rhythm and blues was essentially the

same thing.

Once he realized that, he began to encourage country artists to record blues

and rhythm and blues songs to which he held the copyrights and vice versa,

blues and rhythm and blues artists record country songs.

So that was one way that he helped to break down a barrier. A more important

way was King had probably the first integrated staff of any record company in

the country, primarily through the hiring of Henry Glover. In the mid-1940s,

Henry was a black musician, song writer, record producer, arranger, and in the

early years of King, he was essentially the number two man, second only to Syd

Nathan. And Henry produced the blue and rhythm and blues that he might have

been expected to, but he also produced a lot of country recordings.

GROSS: Now, you mentioned that what Syd Nathan, the founder of King Records,

would do, since he had rhythm-and-blues artists and country musicians signed to

the label, he would take songs that he held the copyright to and have both a

rhythm and blues performer and a country group recorded. And I want to play an

example of that, and this was â this is Hank Ballard doing âFinger Poppinâ

Time,â which was a pretty big hit for him, and then the Stanley Brothersâ

version of the same song. Iâm assuming the Hank Ballard came first.

Mr. FOX: Yes, yes it did. Itâs a Hank Ballard original.

GROSS: He wrote it.

Mr. FOX: Yes.

GROSS: Okay, so do I have anything to say? Do you have anything to say about

this pairing before we hear it?

Mr. FOX: Itâs one of my favorite Stanley Brothers songs. Itâs kind of an odd

duck in their catalog. They were among the most traditional bluegrass artists

of the time, but they also hadnât had a hit in a long time, and bluegrass was

kind of on life support in the late â50s and early â60s when they were making

these records for King.

Syd Nathan asked them to do this song, and they really had no reason to refuse

him. So they did it.

GROSS: Okay, so hereâs Hank Ballard, followed by the Stanley Brothers, doing

the Hank Ballard song, âFinger Poppinâ Time.â

(Soundbite of song, âFinger Poppinâ Timeâ)

Mr. HANK BALLARD (Musician): (Singing) Hey now, hey now, hey now, hey now, it's

finger pop poppin' time, finger poppin' poppin' time. I feel so good, and

that's a real good sign.

Hey now, hey now, hey now, hey now, hey, baby, come along with me. Hey, hey,

hey baby, come along home with me. Weâre going to sing it to the brink, just

wait and see.

(Soundbite of song, âFinger Poppinâ Timeâ)

THE STANLEY BROTHERS (Music Group): (Singing) Hey now, hey now, hey now, hey

now, it's finger pop poppin' time, finger poppin' poppin' time. I feel so good,

and that's a real good sign.

Here comes a Mary, here comes Sue. Here come Johnny and a Bobby, too. It's

finger pop poppin' time. I feel so good, and that's a real good sign. Hey now,

hey now, hey now, hey now, hey babyâ¦

GROSS: We just heard the Stanley Brothersâ version of âFinger Poppinâ Time,â

which was originated by Hank Ballard, whose version we first heard. They were

both recorded in 1960, both for King Records, and one of the things King

Records specialized in was having country and rhythm and blues artists on the

same label. My guest, Jon Hartley Fox, has just written a new book about that

record label, which is called âKing of the Queen City.â

Well, itâs really fun to hear those back to back. Now, another record that you

write about in your book about King Records is the song âGood Rocking Tonight,â

originally recorded by Wynonie Harris in 1948. You make the case that this King

record was actually the first rock and roll record. And as you concede, many

people would make the case that Ike Turnerâs âRocket 88â was really the first

rock and roll record that came a few years later. Why do you consider Wynonie

Harrisâ âGood Rocking Tonightâ the first rock and roll record?

Mr. FOX: That was kind of a goofball claim I made in the book because itâs

obviously something that is open to endless debate. But it had the right

attitude, and the key was it crossed over to white record buyers, not as much

as later King records in the early â50s did, but this was one of the first, I

think, that was heard by white teenagers in fairly large numbers. Evidence of

that is Elvis Presley. This is one of Elvisâ favorite songs and one of the

first ones he recorded.

GROSS: Is there a story behind how Wynonie Harris ended up recording this for

King?

Mr. FOX: Yeah, the song was written by Roy Brown, who recorded for DeLuxe,

which was a King subsidiary after a while. And Roy wrote this song and

approached Wynonie Harris at one of Wynonieâs gigs and tried to sell him the

song for I believe $50, and Wynonie blew Roy Brown off.

So Roy was broke. He needed some money. So he recorded it himself for DeLuxe

Records. A man named Cecil Gant, a singer who had had some success on DeLuxe,

intervened for him with the Braun Brothers, who owned the label, and got Roy a

quick contract on DeLuxe.

He recorded the song and was beginning to have a hit with it, certainly a

regional hit down around New Orleans, and working its way across country. When

Wynonie Harris saw that Roy was beginning to have a hit with the song, he

remembered blowing it off and realized his mistake. So he hustled into the King

studios in Cincinnati and cut pretty much an exact copy of Roy Brownâs version.

But because of Kingâs far superior distribution and marketing, Wynonie got the

hit on the record. So he made an initial mistake, but he corrected it.

GROSS: Weâll talk more about King Records and hear more music in the second

half of the show. Jon Fox is the author of âKing of the Queen City: The Story

of King Records.â Iâm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Iâm Terry Gross, back with Jon Fox, the author of the

new book, "King of the Queen City: The Story of King Records." The Cincinnati-

based label was founded in 1943 by Syd Nathan, who ran it until 1971.

King recorded country, blues, and rhythm and blues, launched the career of

James Brown, and released the original versions of "Fever," "The Twist" and

"Good Rockin' Tonight."

Now King Records also had a reputation for recording some songs with sexual

overtones or double entendres. One of the big examples would be The Dominoes

recording of "Sixty Minute Man." So was there - were there problems with either

radio stations not wanting to play it or parental negative reaction? Like, what

was the response to these sexual innuendo kind of songs?

Mr. FOX: Well, those songs were pretty universally banned from radio airplay

and were condemned from every pulpit - public and secular. But kids loved it.

Syd Nathan was not the first to find that controversy doesnât hurt record sales

in the slightest, and this was one of the first big crossovers, and that white

kids bought by the thousands. And I think that that was the real reason for the

controversy was it came really to the first time of the attention of a lot of

moral arbiters of the country.

GROSS: So from the early 1950s, here's The Dominoes recording of "Sixty Minute

Man."

(Soundbite of song, "Sixty Minute Man")

THE DOMINOES (Rhythm and blues group): (Singing) Ooh, ooh, ooh, ooh, ooh, ooh,

ooh, ooh, ooh. Sixty minute man. Sixty minute man. Look here, girls, I'm

telling you now. They call me loving Dan, I'll rock 'em, roll 'em all night

long. I'm a sixty minute man. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. If you don't believe I'm all I

say, come up and take my hand. Ooh, hoo, hoo, hoo. When I let you go, you'll

cry, oh yes, heâs a sixty-minute man. There'll be fifteen minutes of kissing,

then you'll holler, please don't stop. Donât stop. There'll be fifteen minutes

of teasing, fifteen minutes of pleasing, and fifteen minutes of blowing my top.

Mop. Mop. Mop.

GROSS: That's The Dominoes recording of "Sixty Minute Man" on the King Records

label and the King label is the subject of the new book "King of the Queen

City" - the Queen City being Cincinnati. My guest is the author of the book,

Jon Hartley Fox.

GROSS: Of all the performers signed by King, probably the most successful, the

most famous, the most groundbreaking - was James Brown. How did King Records

end up signing James Brown?

Mr. FOX: Ralph Bass was a producer and talent scout for King Records. He ran

Federal Records, which was one of their subsidiaries. And he for most of each

year, traveled the country looking for talent. He ran across a demo tape of

James Brown at an Atlanta radio station, found that they were in Macon, went

there, finally made connection with a mover and shaker named Clint Brantley,

and then went to hear James, and Ralph was blown away them - Ralph Bass was.

He offered them an immediate contract to come up to Cincinnati and record -

there was a song on the demo that Ralph was particular impressed by called

"Please, Please Please." And that was the main song he wanted, so he went after

him, heard him at a club in Macon, Georgia and signed him on the spot - beating

Chess Records to the punch.

GROSS: And "Please, Please, Please" was the first record that James Brown

released on the King label.

Mr. FOX: Yes.

GROSS: And it was a big hit?

Mr. FOX: It was a big regional hit. It wasnât really a national hit, but it was

a big enough hit that it got some national notice.

GROSS: Now the way you tell the story in the book, Syd Nathan - the owner of

the label, the founder of the label - didnât like this record and didnât like

the idea of releasing it.

Mr. FOX: He hated the record. He had several caustic comments about it and

actually interrupted the recording studio, yelling at Ralph Bass that nobody

wanted to hear this kind of music. And he threw a big tantrum and Ralph Bass

finally just challenged him and said look, I know what this is. I know that

I've got a hit here. You just put the record out in Atlanta, Georgia and if

itâs not a hit there, I'll quit. I'll just quit. You donât have to fire me. I

quit. Ralph was that sure of it and that mollified Syd enough that he went back

into the control room and after everybody got their composure regained, they

went ahead and recorded that song.

GROSS: So did Syd Nathan, who didnât like this record very much and founded the

record company, end up making peace with James Brown when he realized how

popular and how lucrative it was to be affiliated with James Brown?

Mr. FOX: There's was an uneasy peace. They basically went through the same and

dance every record. James wanting to do what - James road tested his material

before he recorded it, so he had a pretty good idea what was working at the

band's appearances, what really shook up the audience and what they didnât care

for.

Syd, on the other hand usually viewed all of James ideas as terrible and all of

the music as just unreleaseable. And they fought that battle and James

outsmarted various ways, worked around him various, and the records were always

successful, like the "Live at the Apollo," James had to pay to record that

himself, but then once Syd Nathan realized how good it was and what he had, he

bought it from James.

GROSS: Now Syd Nathan eventually own a piece of every aspect of the record

business. Correct me if I'm wrong here. He had studios; he had a pressing

plant, a distribution company, a trucking business. Am I missing anything?

Mr. FOX: Yeah. He actually made turntables for a while.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Oh, all right.

Mr. FOX: They sold King - well, he didn't make them, but they sold King

turntables - King record players.

GROSS: So...

Mr. FOX: So you could actually get the whole thing under one roof.

GROSS: I think weâve probably done a better job in showcasing a little bit of

the rhythm and blues that King recorded than the country. Would choose one of

your favorite country recordings that came out of King?

Mr. FOX: "Blues Stay Away From Me," by the Delmore Brothers.

GROSS: And why are you choosing that?

Mr. FOX: Well, I think it's a great song, first of all. That's what Syd Nathan

would want me to say. It's a great song...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. FOX: ...that it stood the test time. But it also in one song recorded in

one day at the recording studio in Cincinnati, it kind of demonstrates the King

model at work. It was an in-studio collaboration between the two Delmore

Brothers, Alton and Rabon, who were from North, Alabama; Wayne Raney, a

harmonica player from Arkansas - those three were white, from the South, and

them Henry Glover, the producer of the song - the producer of the recording

session and the co-writer of the song.

The four of them in the studio worked up the song from ideas that Alton Delmore

and Henry Glover brought to the table and the entire process was an equal

collaboration between those four men. And I think that that just kind of

illustrates the way that King let their artists do what they wanted to do but

also helped introduce them to different things, like Syd Nathan wanting the

Stanley Brothers to record "Finger Poppin' Time" or wanting some of these other

country artists to record these black songs that he or these R&B and blues

songs that he had the control of that he thought were good songs. This was -

just sort of in one song - it was the distillation of the King model at work.

GROSS: Well, Jon Fox, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. FOX: Thank you very much for having me, Terry.

GROSS: Jon Hartley Fox is the author of the new book "King of the Queen City:

The Story of King Records."

(Soundbite of song, "Blues Stay Away From Me")

THE DELMORE BROTHERS (Country band): (Singing) Blues, stay away from me. Blues,

why don't you let me be? Don't know why you keep on haunting me. Love, was

never meant for me. True love was never meant for me. Seems somehow we never

can agree.

GROSS: Coming up, Seymour Stein, a founder of Sire Records talks about getting

his start at King Records.

This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

113826003

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20091015

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Seymour Stein, From King To Sire Records

(Soundbite of music)

TERRY GROSS, host:

My guest, Seymour Stein founded Sire Records and signed Madonna, The Ramones

and Talking Heads, launching their careers. Stein learned the record business

at King Records where founder, Syd Nathan became his mentor. At Nathan's

funeral, Stein was one of the pallbearers. When Nathan was inducted into the

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Seymour Stein was the presenter.

Stein was only 14 when he met Syd Nathan. At the time, the young Stein was

working at Billboard magazine. Billboard used to host listening sessions where

record company owners would play their recordings and try to persuade Billboard

to give them a good review. Stein met Syd Nathan at one of those sessions.

Mr. SEYMOUR STEIN (Entrepreneur, vice president of Warner Brother Records): I

remember that session, you know, like it was yesterday, and it was over 50

years ago. Syd was there and another record man was there as well. What I

remember very clearly was there were a large amount of records to listen to and

the last two or three were on the Jubilee label and one of the reporters said

on, I hear Jubilee Records is going out of business. Why should we even bother

with these records? He said I'm sure, you know, Syd is getting a little bored

here. And Syd said, in the way he spoke and he said what if I wasnât here?

Would you talk that way about me? Listen to these records. And so, the person

said boy, Jerry Blaine, who was the owner of Jubilee Records, he said, he must

be a good friend of yours. And he said, oh no, I'm suing the son of a bitch.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. STEIN: And he said but what's right is right, you know, and one of the

records actually became a hit. I can't remember. It might've been "White Silver

Sands" By Don Rondo or something like that. So...

GROSS: So how did you get to work for Syd Nathan?

Mr. STEIN: He invited me out to spend the summer with him. I was still in high

school. I was 15 and I said yeah, wow. And my parents were a bit, you know - my

father was an Orthodox Jew and, you know, and just didnât understand all of

this. And I brought them up to Billboard and an appointment was made, which I

didnât talk to my parents for a couple of weeks. I was so embarrassed that they

would, you know, question something that was so wonderful. And just as they

walked into Syd's office he put out his - my father's cheap cigar and Sydney

immediately reached into his pocket and gave him a Havana, which my father was

not use to and he had my father in his pocket.

And he said well, he said Seymour here, he's got shellac in his veins, and what

a compliment. It meant that, you know, I was a record man. You know, because

shellac was the main ingredient in old '78. And then he explained that to my

father. He said if you donât let him do what he wants to do he's going to wind

up doing nothing and you'll have to buy him a newspaper route because that's

all he'll be good for. And this was April. And my parents rushed home and when

I got home, everything was packed. I wasnât supposed to leave until the end of

June when high school was up.

GROSS: So how old were you when you went to work with Syd Nathan at King

Records full time?

Mr. STEIN: Full time was 1961, â62. So, I would have been 19 or just turning

20.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Now, one of the things that Syd Nathan did for you after you

said working with him at King Records was tell you to change your name. Your

real last name was?

Mr. STEIN: Oh, I was born with the name Steinbeagle(ph), Seymour Steinbeagle.

GROSS: And what was wrong with that in Syd Nathanâs eyes?

Mr. STEIN: It was too long. And he kept asking me to change it and I didnât

want to hurt my fatherâs feelings. My father was the eldest son and both his

brothers had changed their name, had shortened it. But he felt, out of respect

to his father, he should keep it.

GROSS: So - but you did change it?

Mr. STEIN: Well, yes. Not everybody had phones at King Records. People shared

phones, as much as three or four people could share a phone at one time. But

there was a paging system and the switchboard operator had one microphone and

Syd had the other one on his desk. And I was being paged, an incoming call -

Seymour Steinbeagle, pick up the closest phone, Seymour Steinbeagle, thereâs a

call. And she was repeating it over and over again. And all of the sudden,

Sydâs voice came on, he said, oh, no, itâs Stein or Beagle or back to New York.

And I wasâ¦

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. STEIN: I almost started to cry, I was so embarrassed. And I changed my name

and Iâm very glad that I did.

GROSS: So, you got started at Billboard Magazine. Do you ever miss the

importance of the charts, the days when, like, top 40 really meant something?

Mr. STEIN: I miss it a lot.

GROSS: What do you miss about it?

Mr. STEIN: I miss all the excitement. I mean, thatâs how I heard about

Billboard. There was this disc jockey, long before rock and roll, Martin Block.

GROSS: WNEW in New York.

Mr. STEIN: Yes.

GROSS: Make believe ballroom.

Mr. STEIN: Exactly.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. STEIN: Itâs make believe ballroom time and free to everyone. Well, I would

come back on Saturday mornings from the synagogue and have the - my radio sort

of under the pillow, so my father couldnât hear it when he came home, listening

to Martin Block play the top 25 off the Billboard chart and later he started

playing, in addition, the top five R&B and the top five country and western.

And thatâs how I got introduced to Johnny Cash and Ray Price and Hank Williams,

on the one hand, and to some of the R&B records, to my idol, Fats Domino, as

well. Radio was very important and the charts - and they played the Billboard

charts. That was what Martin Block played off of and thatâs how I knew to go up

to Billboard.

GROSS: So, you miss it, you miss those days of the charts?

Mr. STEIN: Oh, I sure do. Oh, yes.

GROSS: Seymour Stein, a pleasure to talk with you, thank you so much.

Mr. STEIN: Youâre very welcome.

GROSS: Seymour Stein founded Sire Records and got his start at King Records

with Kingâs founder Syd Nathan. The new book about King Records, âKing Of The

Queen City,â was written by Jon Hartley Fox. We want to thank Brian Powers for

all his help with our show about King. Heâs the music librarian at the Public

Library of Cincinnati and has done extensive research on King.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

113826637

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20091015

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Monty Python 40 Years Later: âThe Lawyerâs Cutâ

TERRY GROSS, host:

Beginning Sunday, IFC - the Independent Film Channel - presents a six evening,

six-hour documentary about âMonty Pythonâs Flying Circus,â timed to commemorate

the 40th anniversary of the groundbreaking British TV series and comedy troupe.

Itâs called âMonty Python: Almost the Truth (The Lawyers Cut)â and our TV

critic David Bianculli has this review.

DAVID BIANCULLI: Itâs good to know after all these years that the surviving

members of Monty Python still canât even take themselves seriously. Oh, they

have the best of intentions with this new mega documentary called âMonty

Python: Almost the Truth (The Lawyers Cut).â They really do want to explain

where their peculiar sense of humor came from and how the six of them met and

the inspirations for their most famous sketches, record albums, movies and

stage shows.

But just as the original âMonty Pythonâs Flying Circusâ poked fun at the

stiffness of the BBC when it premiered on the BBC back in 1969, this new

documentary canât help but send up the documentary form a little. Its

individual hours sport such titles as âThe Not-So-Interesting Beginningsâ and

âThe Much Funnier Second Episode.â And for the theme song of this new

production, the Pythons not only resurrected the main title music from âThe

Life of Brian,â but a dead ringer for the original vocalist as well.

(Soundbite of âMonty Python: Almost the Truth (The Lawyers Cut)â theme song)

Unidentified Woman (Singer): (Singing) Python, the brand-new documentary of

Python. Itâs a new documentary. Itâs about Monty Python. Unlike other Monty

Python documentaries, this is brand new. Itâs a new documentary. Itâs not

complimentary, but itâs better than a hysterectomy. Itâs Monty Python.

BIANCULLI: Thereâs an added joke, in that each hour has its own theme song,

which is sung with increased frustration over how endless the documentary is,

and how familiar the material. Obviously, the Pythons are sensitive enough to

this charge to make a pre-emptive strike. After all, there was a 30th

anniversary Monty Python TV special a decade ago, and a 20th anniversary one a

decade before that. And home-video collectors have had more than one

opportunity to buy a âMonty Pythonâs Flying Circusâ mega set on DVD.

But for such familiar terrain and such an old comedy group, thereâs a lot of

new insight here, enough to please hardcore Python fans, and intriguing enough

to turn new viewers into probable converts. My favorite installment is the

first one, which is generous with its clip from the early radio and TV shows

that influenced or featured the future members of Monty Python. Peter Sellers

and his infamously unstructured âThe Goon Showâ was one clear inspiration, the

satiric stage revue âBeyond the Fringe,â with Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and

Jonathan Miller, was another. And the British version of the topical variety

series, âThat Was the Week That Was,â which like âThe Office,â was Americanized

with a new cast, was a third.

Some of the Pythons came from Cambridge, some from Oxford, and American Terry

Gilliam came seemingly out of nowhere. But eventually, the six of them:

Gilliam, John Cleese, Terry Jones, Michael Palin, Eric Idle and Graham Chapman,

found their own styles and voices. They presented a TV show where sketches were

absurd and unpredictable, and where comedy targets ranged from little old

ladies and dead philosophers to the Spanish Inquisition.

Insanely imaginative animation linked one sketch to another. Or as an

alternative, John Cleese would simply stare into the camera and intone, with

the deep seriousness of a BBC announcer: And now for something completely

different. And all of it was completely different, then and now, from the

âMinistry of Silly Walksâ and the âFish-Slapping Danceâ to the âDead Parrot

Sketch.â Hereâs John Cleese returning a recent purchase to pet store owner,

Michael Palin.

(Soundbite of TV Show, âMonty Pythonâs Flying Circusâ)

Mr. JOHN CLEESE (Actor): (As Mr. Praline) I wish to make a complaint.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MICHAEL PALIN (Actor): (As Shop Owner) Sorry, weâre closing for lunch.

Mr. CLEESE: (As Mr. Praline) Never mind that my lad, I wish to complain about

this parrot what I purchased not half an hour ago from this very boutique.

Mr. PALIN: (As Shop Owner) Oh, yes, the Norwegian Blue. Whatâs wrong with it?

Mr. CLEESE: (As Mr. Praline) Iâll tell you whatâs wrong with it. Itâs dead,

thatâs whatâs wrong with it.

(Soundbite of laughter)

BIANCULLI: Except for Graham Chapman who died 20 years ago, all the other

Pythons are alive and well, and contribute fresh interviews to this

documentary. There also are such well-chosen ingredients as clips from a

British TV talk show back when Monty Pythonâs âThe Life of Brianâ was released.

John Cleese and Michael Palin appeared on the talk show to debate an angry

bishop and, in these exchanges, Malcolm Muggeridge, a former satirist and

author, who had just converted to Christianity. He found the Pythonâs biblical

humor positively sacrilegious. In this clip, Cleese and Palin take on

Muggeridge, then Cleese in a new interview for the documentary, recalls Palinâs

atypically biting reaction, which we then hear.

(Soundbite of TV documentary, âMonty Python: Almost the Truth (The Lawyerâs

Cutâ)

Mr. CLEESE: You keep making the basic assumption that we are ridiculing Christ

and Christâs teaching and I say that we are not.

Mr. MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE (British Journalist; Satirist; Author): But you imagine

that your scene, for instance, of the sermon on the mount. The scene in this -

in your film of the sermon on the mount is not ridiculing one of the most

sublime utterances that any human being has ever spoken on this earth. Course

it is.

Mr. PALIN: Absolutely not.

Mr. CLEESE: No, no. Itâs making fun of the guy whoâs remembered it wrong and of

the people who donât understand it and miss the point.

Mr. MUGGERIDGE: Well, I thinkâ¦

Mr. PALIN: I think thatâs really unfair because I think that a lot of people

looking in will think we have actually ridiculed Christâ¦

Mr. MUGGERIDGE: Yes.

Mr. PALIN: â¦physically. Christ is played by an actor, Ken Colley, he speaks the

words from the sermon on the mount. Itâs treated absolutely respectfully. The

camera then pans away, we go right to the back of the crowd to someone who

shouts speak up because they cannot hear him.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. PALIN: Now I mean if that utterlyâ¦

Mr. MUGGERIDGE: No, no.

Mr. PALIN: â¦if that utterly undermines their faith in Christ thenâ¦

Mr. MUGGERIDGE: No, no.

Mr. CLEESE: That was kind of fun. What was particularly fun, it was the

crossest Iâve ever seen Michael Palin.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CLEESE: Not a man whoâs easily upset. Heâs almost apoplectic.

Mr. MUGGERIDGE: I started off by saying that this is such a tenth rate film

that I donât believe that it would disturbâ¦

Mr. PALIN: Yes, I know youâve started with an open mind, I realize that.

Mr. MUGGERIDGE: â¦anybodyâs faith.

(Soundbite of laughter)

BIANCULLI: If I have a complaint about this six-hour documentary, itâs that it

could have been longer. Eric Idleâs recent musical stage triumph, in which he

turned the movie âMonty Python and the Holy Grailâ into the Broadway hit

âSpamalot,â is covered but we donât hear from David Hyde Pierce, Hank Azaria or

other members of that show, including Sara Ramirez, now on âGreyâs Anatomy.â

And if âSpamalotâ gets its due, why not other Python solo ventures, like Eric

Idleâs âThe Rutles: All You Need Is Cash,â Michael Palinâs âRipping Yarns,â

John Cleeseâs âFawlty Towersâ or Terry Gilliamâs âBrazilâ â all of them

brilliant.

Yes, thereâs room for even more. And the DVD version of âThe Lawyerâs Cutâ

includes an additional disc, which does feature among other things, the origin

of âFawlty Towers.â But even if you just watch the televised version on IFC,

youâll be quite entertained. And stay till the very end, because the credits on

the last episode close with one final, very solid laugh. Itâs too good to

spoil, but just like Monty Python, itâs something completely different.

GROSS: David Bianculli writes for tvworthwatching.com and teaches television

and film at Rowan University. You can download podcasts of our show on our Web

site freshair.npr.org.

Iâm Terry Gross.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

113798152

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.